![]()

1 Introduction

Kiyoshi Kobayashi, Khairuddin Abdul Rashid,1 William P. Anderson and Masahiko Furuichi

1 ASEAN and AEC

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has grown into an important player in the world economy. The combined population of the 10 member states in 2014 is 622 million, which is the third largest in the world following China (1,367 million) and India (1,259 million). The combined GDP in 2014 is US$2.5 trillion, which has almost doubled from US$1.33 trillion in 2007. With this high growth rate, the population with an income of more than US$5,000 is estimated to grow from 300 million in 2015 to 400 million in 2020. The member states combine, therefore, to form the world’s most important emerging consumer market. In addition, ASEAN has two advantages as a production base. First, ASEAN is well placed between two huge consumption markets: China and India. Second, ASEAN has a large and diverse labor force comprising both skilled workers and diligent low wage labor.

The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), formally established on 31 December 2015, is a framework of regional economic cooperation to facilitate regional growth through free trade and market integration. The establishment of this economic community is a key milestone for the ASEAN region as an emerging economy. The concept of AEC was first stated in 2003 at the 9th ASEAN Summit. The AEC Blueprint 2015 was initiated in 2007 with the following four strategic goals.

- 1 Single market and production base: free flow of goods, free flow of services, free flow of investment, free flow of capital, free flow of skilled labor.

- 2 Competitive economic region: competition policy, consumer protection, intellectual property rights, infrastructure development, taxation, e-commerce.

- 3 Equitable economic development: small and medium enterprise (SME) development, support to less developed member states.

- 4 Integration into global economy: comprehensive free trade and economic partnership agreements (FTAs/EPAs), enhanced participation in global supply networks.

This book primarily addresses the free flow of goods within ASEAN and with the rest of the world. It is a core element of the AEC to achieve the first goal, a single market and production base. ASEAN has been implementing strategic measures for the free flow of goods: elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers, and trade facilitation. The development of transportation infrastructure (in the second goal) and integration into global economy (the fourth goal) also facilitate the flow of goods by reducing the cost of private firms in supply chain and logistics.

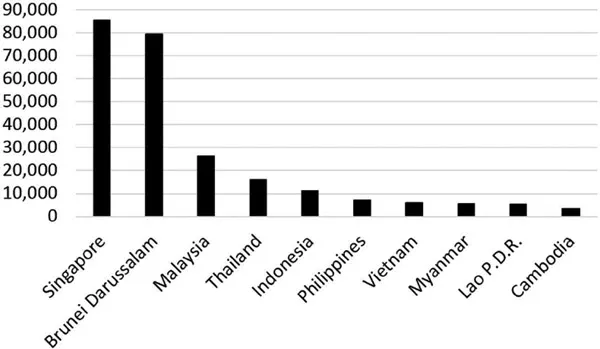

Although this book mainly focuses on development policies to facilitate the free flow of goods, the book also pays attention to equitable economic development, the third strategic goal of the AEC. Achieving this goal is necessary not only to meet fairness requirements but also to encourage cooperation among the member states. The variation in development levels among the members is large, as shown in Figure 1.1. The GDP per capita of Singapore is more than 24 times higher than that of Cambodia. Even if the top three countries are ignored, the GDP per capita of Thailand is 4.6 times higher than that of Cambodia. This large gap can discourage low-income members from harmonizing the institutional framework toward greater economic integration. This book also tries to give direction on how to narrow this gap.

2 Progress of the AEC – focusing on flow of goods and equitable development

According to an evaluation by the ASEAN Secretariat, 469 out of 506 high-priority measures (92.7 percent) in the strategic goals in the Blueprint 2015 have already been implemented. However, details of the implemented measures are not open to the public. The actual progress still has a long way to go toward completion. Economic integration will continue to progress gradually in the next 10 years under the AEC Blueprint 2025, which was initiated in 2015.

Figure 1.1 PPP adjusted GDP per capita (in current international $) of the member states as of 2015

2.1 Free flow of goods

Significant progress has been made in intra-regional tariff elimination. The ASEAN-6 (Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) have virtually eliminated all intra-regional tariffs, with 99.2 percent of tariffs at 0 percent. The rest of the countries, known collectively as CLMV (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam), had eliminated 91 percent of intra-regional tariffs by the end of 2015, having been allowed to postpone eliminating tariffs on influential products such as automobiles and motorcycles until 2018. Of comparable importance is the fact that ASEAN has also concluded five comprehensive FTAs with China, India, Japan, Korea, and Australia/New Zealand.

However, the elimination of non-tariff barriers has made less progress. Although some technical standards and requirements have been harmonized, other kinds of non-tariff barriers, such as quotas and import permits, remain prominent. A number of problems also exist in the area of cross-border management, such as the complicated customs procedures that are in some cases unique to individual member states. Accordingly, the AEC regards trade facilitation as critical to reducing the administrative (paperwork) cost and waiting times at border crossings.

Transportation infrastructure (road, rail, port, and airport) has been developed to enhance physical connectivity, especially in the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS, namely Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, and a part of China). Three international highways have been constructed to connect major cities in the sub-region: the North-South Economic Corridor (Hanoi–Kunming–Bangkok), the East-West Economic Corridor (Da Nang–Savannakhet–Mawlamyaing), and the Southern Economic Corridor (Ho Chi Minh City–Phnom Penh–Bangkok).

There is still, however, a significant gap between transportation demand and infrastructure capacity. Further infrastructure development is necessary in order to accommodate the growth of demand as well as to narrow the development gaps. Intra-regional physical connectivity is especially weak in the port-dependent members: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, all of whom trade less with the other member states than with markets outside of ASEAN. Development of land transportation between Thailand and Malaysia as well as maritime transportation among the island countries will play a vital role in realizing an integrated transportation network within the region.

2.2 Equitable development

SME development and support to less developed member states are the two core elements of equitable development. SMEs comprise over 90 percent of the enterprises in ASEAN, generating over half of the employment in the region. As such, it is indispensable to equitable development that SMEs be encouraged to participate in regional and global value chains. The AEC aims to enhance the competitiveness of SMEs through improved access to finance, markets, human resources, information and advisory services, technology, and innovation. ASEAN has developed information and advisory services for SMEs, but the implementation of financial support to them lags behind.

In order to narrow the development gap among member states, ASEAN has implemented the Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI), which invests in development projects of the CLMV. However, the impact of IAI has been limited because of the small budget. The total budget of Work Plan I (2002–2008) was US$211 million, and that of Work Plan II (2009–2015) was US$20 million until 2014. This small budget reflects the limited financial capacity of the ASEAN Secretariat and the local governments. Foreign aid from international organizations and external countries will play an important role in filling the development gap.

3 Concepts of this book

The AEC Blueprint 2015 was not fully realized by the end of 2015. Although significant progress has been made in intra-regional tariff elimination and comprehensive FTAs, inadequate capacity of transportation infrastructure and inefficient cross-border management in some member states still inhibit integration both internally and with the global market. Looking to the future, the AEC Blueprint 2025 recognizes the importance of these two issues. It underlines trade facilitation as strategic measures for greater free flow of goods. Developing an integrated transportation network is emphasized in support of a new strategic goal, “enhanced connectivity and sectoral cooperation.” The need to enhance “ASEAN connectivity,” which was already stated in the 2010 Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC). Recalling a theme from 2010 Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC), Blueprint 2025 calls for “the seamless movement of goods, services, investment, capital, and skilled labour within ASEAN in order to enhance ASEAN’s trade and production networks, as well as to establish a more unified market for its firms and consumers.” Physical, institutional, and people-to-people linkages between member states and the rest of the world are keys to the AEC’s continued economic expansion, productivity growth, resilience to external shocks, and reduced development gap.

At this crucial moment, the planners in ASEAN should seek effective policy for infrastructure development and trade facilitation to enhance ASEAN connectivity. This work is challenging for three reasons. First, development policy is constrained by the limited financial capacity of the member governments. In order to effectively use the limited financial resources, it is necessary to evaluate and prioritize infrastructure projects and trade facilitation measures. Second, accurate evaluation of the projects and policies requires knowledge about supply chains, logistics, and economics, which are complicated systems governing the flow of goods and business location. Third, development policy should also be equitable and inclusive in order to narrow the development gaps of the member states and eradicate poverty.

This book is a compilation of selected papers presented at conferences held by Kyoto University and International Islamic University of Malaysia. With the aim of providing insights for the development of policy to enhance ASEAN connectivity and realize region-wide equitable growth, the Graduate School of Management, Kyoto University, Japan, and the Kulliyyah of Architecture and Environmental Design, International Islamic University of Malaysia, have held three academic conferences. The first conference took place in Manila, the Philippines, in March 2014; the second in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in March 2015; and the third in Vientiane, Lao PDR, in February 2016. This book includes papers presented, reviewed, and discussed at those conferences. Chapters that follow include extensive discussions and analyses on the development of infrastructure, institutional frameworks, and supply-chain/logistics networks. Several contributors utilize economic models in order to provide quantitative assessments of policies and projects. By providing useful economic models as well as insights from the discussions and analyses, this book seeks to advance the process of creating a more connected, cohesive, resilient, and equitable AEC.

4 Organization of this book

This book is divided into five parts.

Part I discusses general issues regarding regional development from a broader perspective. This part comprises this introductory chapter and Chapters 2–4.

Chapter 2 (by Sakane, K. and JICA Study Team) reviews the opportunities and challenges of ASEAN both comprehensively and neutrally, based on a study conducted by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Following the review, it points out the necessity of further equitable integration for regional competitiveness as well as policies to address emerging issues, such as the aging society, domestic disparities, the expansion of food and energy demand, and increased disaster risks.

Chapter 3 (by Lynch, J., Perdiguero, A. and Rush, J.) summarizes the past and future roles of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in the regional development of ASEAN. ADB has been contributing to the AEC through financial support and technical assistance. Such international aid is indispensable for ASEAN because of the limited financial and human resources of the member governments. The chapter also outlines the central issues of the AEC from the viewpoint of an aid agency, including infrastructure development and trade facilitation.

Chapter 4 (by Ray, G.) develops theoretical arguments for cross-border economic partnership and inclusive growth in the context of ASEAN–India Comprehensive Partnership. With its large, growing market and proximity, India is an important partner for ASEAN. This chapter first summarizes past economic growth and relations between ASEAN and India. Then, the paper develops theoretical arguments to lay out an illustrative roadmap for an ASEAN–India partnership. The developed theory gives general insights into how the partnership promotes inclusive development.

Part II presents some ideas for improving institutional frameworks to enhance connectivity and encourage integration. This part comprises Chapters 5–7.

Chapter 5 (by Anderson, W. P.) reviews the history of economic integration in NAFTA, with emphasis on the development of cross-border supply chains. Both the AEC and the NAFTA have large shares of intermediate goods in their internal trade. This means that trade facilitation can have critical impacts on the competitiveness of the economies since a variety of industries use cross-border supply chains. Various topics are addressed regarding cross-border management. After similarities and differences between the two trade blocs are defined, lessons for the AEC are drawn from the NAFTA area.

Chapter 6 (by Khairuddin, A. R.) assesses the prospect of having a common Public Private Partnership (PPP) framework for ASEAN. The development of infrastructures in ASEAN is often constrained by the limited financial and human resources of the member governments. Public Private Partnership (PPP) is considered to be the most viable alternative and is also encouraged in the ASEAN Blueprint 2025. This chapter first examines PPP implementation in ASEAN member states to find inconsistency in implementation frameworks, which can present problems. Then, it presents the prospect of a common PPP framework and highlights key areas to be harmonized.

Chapter 7 (by Song, H.) presents supply chain finance as a solution for the working capital problems of SMEs in ASEAN. Supply chain finance is a type of financing where a focal firm (lender) in the supply chain network supplies liquidity to the SMEs in the network based on the operational information collected through the network. Based on case studies in China, this chapter argues that supply chain finance can also improve SMEs’ financing quality in ASEAN. It provides another rationale to facilitate the formation of supply chain networks for equitable development.

Part III focuses on the relation between infrastructure development and business location. This part includes Chapters 8–10.

Chapter 8 (Nakabayashi, J.) discusses the implication of a production strategy called “Thailand-plus-one,” which is adopted by Japanese multinational firms. This strategy transfers the labor-intensive production process from Thailand to neighboring countries (Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar). This is a typical example of cross-border supply chains where the more labor-intensive process is located in the country with the lower wage. Based on case studies of multinational firms, this chapter argues that both development of infrastructure a...