![]()

1 | Stress: A Problem of Definition |

1. THE UMBRELLA TERM OF “STRESS”

The term “stress” is an umbrella term for an increasingly wide variety of conditions, responses, and experiences. A fundamental problem for any writer or researcher concerned with stress and its effect on behaviour is to attempt to find an adequate definition.

There have been a number of attempts to provide comprehensive definitions of stress; each has its own problems; each is inadequate in some respects. A useful initial classification of these approaches is in terms of stimulus variables, response variables and internal variables, usually termed independent, dependent and intervening, variables, respectively.

A. Definitions Based on the Independent Variable (Stimulus Features)

A definition of stress in terms of the independent variable has the advantage of giving “out-thereness” to stress variables. Stress is assumed to be a condition of the environment. The environment could be physical or psychosocial. On first consideration, such an approach seems to provide a reasonable basis for classifying stresses. The only problem is to provide a definition of what constitutes a stressful as compared with a non-stressful condition of the environment. The obvious solution is to assume that stress is merely an intense level of stimulation and that it is the level, or intensity, which is the distinguishing factor. Thus stress could be seen as an “intense level of everyday life”: It is too high a level of temperature, too high a level of noise, too high a level of stimulation. Stress is merely a level on a dimension of stimulation that will eventually result in pain. However, this definition does not account for ways in which absence of stimulation might be stressful. Greater generality can be given if it is assumed that extremes rather than excessive stimulation are stressful. Such a bipolar conceptualisation allows isolation and lack of stimulation also to be stressful.

The responses that characterise the behaviour of an individual under stress can be seen as part of an attempt to avoid or escape extreme conditions of the environment. Characteristic physiological changes can be envisaged as part of the attempt to mobilise resources in order to avoid exposure. Cannon (1932, 1936) was the first to hypothesise that physiological changes associated with exposure to stress formed part of a homeostatic response pattern designed to mobilise sugar and oxygen resources resulting in the release of energy. Extending this notion, behavioural changes could be seen as the result of underlying changes in physiological systems associated with the provision of energy.

There are two ways in which a definition of stress in terms of the independent variable accounts for the variety of response patterns that characterise the individual confronted by stress. First, the external condition could be thought of as exerting a force or pressure. The response is then seen as part of strain causing breakdown or damage. Physiological and behavioural responses to stress are then envisaged as malfunctions in relation to too much pressure. The extreme result of increasing malfunction might be mental breakdown and disorder, but there would be no clear indication of what form disorder might take.

A second approach involves the hypothesis of homeostasis: Stress is an invasion of the organism’s normal range of comfort; it is a state of discrepancy. The organism is essentially hedonistic, avoiding pain and seeking pleasure. It therefore mobilises resources in a way designed to attenuate exposure or, if possible, to terminate the stress: The form of the response and its success determines whether the result is perceived as challenging (positive) or distressing (negative).

Some problems with a definition of stress in terms of the state of the independent variable are: (1) that there is an implicit assumption that what is stressful for one person will also be stressful for another; (2) there is no simple way of deciding on what is the limit of tolerance, or at what point a level becomes stressful. Cut-off points may differ for different individuals and be subject to range effects produced by previous experiences, including stressful experiences. This is best illustrated by the engineering model developed by McGrath (1974) in which force or pressure (stress) is exerted by an environment and the response reveals the strain. The total effect is transactional, depending as much on the structure or property of a material as it does on characteristics of the stimulus. Moreover, the effect of stress may be cumulative; a structure may first show no change but later crack or crumble, although the same force is exerted throughout.

B. Definitions Based on the Dependent Variable (Response Features)

Response-based definitions might be thought at first to have many advantages. A substance or person can be deduced to have been exposed to stressful conditions if signs of strain are present. This is like saying that “intelligence is that which intelligence tests test”—stress is that which is responded to by behaviour characteristic of stress. The view has the advantage that personal meaning and so-called neurotic sources of fear are included: If a person responds to the presence of an apple by stressful response patterns, then by definition an apple is a source of stress.

A problem is that it may be difficult to define and distinguish responses that are part of the stress response from those that are not. The original view of the physiological response to stress developed by Selye (1956) was that it was an undifferentiated state of heightened arousal and hormone activity. On this view it would be relatively straightforward to conduct a test to determine which of two hidden individuals was experiencing stress, by measuring physiological or behavioural response levels. However, more recent research has tended to emphasise both stimulus-specific and person-specific response patterns and the possibility of fractionation between different arousal systems (see Lacey, 1967; Lacey, Bateman, & Van Lehn, 1953). Thus it may be necessary to define which “end-organ” responses, as part of a total pattern, are signs of stress, and which are not. A person may sweat for reasons other than being under stress, and sweating alone as an end-organ response would not provide an adequate definition. The presence of circulating stress hormones such as catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) or corticoid hormones (cortisol) could provide the basis for a definition, but there is a time course associated with the production and excretion of these hormones and the time of assessment may well determine the level. Also, characteristically, the human response to stress can occur in advance of an actual event, or may appear in reflective thought when an event such as a tragic loss has passed. Therefore the stress response may be dissociated in time from the source of the problem.

Finally, a further difficulty arises from the fact that a number of dependent variables change in stress and that one variable (the controlling variable) may change to protect a second variable (the controlled variable).Therefore different impressions may be given of whether or not stress is occurring. A useful illustration is in terms of the bodily responses to raised temperature. In human beings, as environmental temperatures rise, the mechanism of sweating comes into operation to help maintain stable bodily temperature. If sweating were measured, an impression of a changed response to raised temperature would result. However, if body temperature were measured, a change might be less easily detected.

C. Interactional Definitions of Stress

Increasingly, the main approach to the conceptualisation of stress is interactional or transactional. In simplest terms, it is assumed that mental state or structure determines the presence or absence of stress. Thus, as in engineering, where physical structures differ in their capacity to resist external force without showing signs of strain, so in human beings mental structures determine the degree to which stresses are perceived. A useful example is of a study by Symington et al. (1955), which showed that autonomic arousal increased in the case of dying patients who were conscious and not in those who were unconscious. Clearly the presence or absence of the capacity for thought was a determinant of response; the simplest possible equation involves the idea of mediating appraisal processes concerned with dying.

There are various models which have developed the importance of intervening mental activities as important factors in determining stress. The simplest interactional approach is non-specific about the nature of the intervening processes. There is a mediating psychological structure which provides a basis for interpretation of evidence and leads to the classification of that evidence as stressful. Recent interactional approaches however, do provide reasons rather than merely advocating intervening structures.

McGrath (1974) proposed a demand–capacity model in accordance with which the environment imposes demand on the individual but this is only stressful if the individual lacks the capacity to meet that demand. Implicit in this definition is the idea that the individual perceives his capabilities and can make such an appraisal either before he engages the problem or during the scenario created by the problem once he has engaged it. McGrath formulates a set of propositions which he argues provides a conceptual structure for envisaging stress. The focal organism or “actor” can be at a number of system levels—individuals, groups, or organisations. There are then four classes of events. The first class is demand imposed by the environment. The second is reception (recognition or appraisal by the organism) and this creates subjective demand. The third is the focal organism’s response, whether it is physiological or behavioural. Finally there is the consequence of response or results of action. The psychological structure of the individual is seen to be potentially influential at any one of these four stages. For example, individuals may be differentially sensitive to different aspects of the environment, differ in the way demand is perceived, have different subjective assessment of personal capabilities and limitation, or different perceptions of outcome. Essentially, stress is seen to be a relationship between the environment and the organism across these four classes of events.

An earlier approach by Lazarus (1966) provides a foundation for understanding the underlying processes in these four interactional stages. Lazarus distinguished primary, secondary, and tertiary appraisal processes in a potentially stressful situation. Primary appraisals are concerned with interpreting and coding the problem. Secondary appraisals are concerned with the possible response to perceived demand. Tertiary appraisals are concerned with the assessment of the consequence of response. These three types of appraisal are implicit in McGrath’s distinctions.

An interactional view is also provided in an approach linking the state of the independent variable to coping, by Welford (1973). Welford hypothesises that an inverted ‘U’ function relates efficiency in a person’s performance to level of demand, which is in turn determined by the level of stimulation on a scale from tolerable to extreme. Implicit in the Welford model is the notion that at high levels of demand, coping resources are ineffective. Thus, with increasing levels of demand, the probability of imbalance between demand and effective capacity increases. In other words, an individual faced with extreme conditions is less likely to perceive that he has the necessary responses to cope. This provides the basis for an interactional view in which the state of the independent variable is a part determinant of the existence of stress.

Cox has provided the basis for a four-stage transactional model of stress. The main principle of the model is that stress is a personal, perceptual phenomenon rooted in psychological processes (Cox, 1978, p.18). Feedback components are emphasised and a cyclical process is envisaged. Again, there are identifiable stages similar to those provided by McGrath. Demand is determined by the external environment but also by internal needs which may be physiological or psychological. A second stage is determined by the perception of demand and perceived coping ability; imbalance at this stage creates the conditions of stress. Methods of coping available to the individual constitute a third stage. The fourth stage is concerned with the consequences of coping and it is suggested that stress only occurs when the organism’s failure to meet demand is important; in other words, there must be provision for some priority weighting attached to failure. Finally, the model includes the notion of feedback at all stages so that the consequences of failure influence the perception of demand, the perception of the capacity to cope, and the cost attached to failure. The model could be argued to be transactional in the sense that a greater contribution is made by the psychological structure of the individual, than is envisaged in a purely interactional model. McGrath (1976) added a further principle to the main principles described in 1974, and this brings his model closer to a transactional model. He argues, on the basis of findings by Lowe and McGrath (1971), that the closer perceived demand is to perceived capacity, the greater will be the stress. However, Cox finds it implausible to suppose that large imbalances such as might be created by disastrous situations are not stressful, and proposes that stress is likely to be a ‘U’-shaped function of imbalance between demand and capacity. Thus, very small and very large imbalances would be considered stressful.

Fisher (1984a) argued for a more analytical approach to the nature of mediating cognitive processes centred on the perception of personal control. There are two distinguishable paradigms that provide the context for judgements about stress. The first is when a person is coping with a task in the presence of an adverse condition which might be considered stressful. The second is when a person copes with a task but then begins to fail under conditions where success matters. Under these circumstances, the task itself creates the precondition of stress. In both cases the intention or ambition that dictates behaviour is important. Miller, Galanter, and Pribram (1960) were the first to introduce the idea that behaviour is purposefully organised by means of plans. Contained in the blueprint for the plan is the consequence that should be achieved. In the case of the first of the two paradigms above, the purpose may be to attenuate, terminate, or minimise the effects of stress. In the case of the second paradigm the purpose might be re-establish control of the task perhaps by extra compensatory effort when competence is perceived to be low.

This may provide a basis for the definition of stress in terms of personal control: Stress exists when conditions (internal or external) deemed unpleasant cannot be changed. This will occur when demand exceeds capacity, as in the McGrath formulation. An extra element may be the cost of exercising control; if there is only a minor imbalance then a person may decide to expend effort because reversibility of the circumstances he dislikes are within reach. On the other hand, a large imbalance may incur too much cost to correct. The cost of no action must be weighed against the cost of action.

2. THE LINKS BETWEEN STRESS AND THE PERCEPTION OF CONTROL

A. Control as a Factor in Stress

If control is assumed to be a factor which determines stress level then a number of propositions follow. Firstly, the individual should choose and be shown to benefit from being given the means for control (instrumentality). Secondly, the benefits should be greater than would be expected on grounds of predictability only. Thirdly, perceived control should have effects equal to but not greater than objective control. Conversely when a person has control but does not know it, the effect should be the same as when there is no control. Fourthly, individuals must be equipped with the mental resources to determine whether control is possible (otherwise the gains should be no greater than is determined by chance). Fifthly, individuals shown by objective measures to experience high levels of threat should be shown by independent criteria to experience low perceived control. Sixthly, since animals respond to threat with behaviour and physiological activity characteristic of human beings experiencing similar threats, then the propositions listed above should apply to animals.

In the presentation of evidence in succeeding chapters, the interested student might consider whether these propositions are fulfilled or whether the hypothesis that control is a critical factor in stress remains a speculative assumption with intuitive appeal. It is hoped that in succeeding chapters some of the evidence on which these propositions are formulated will be made explicit.

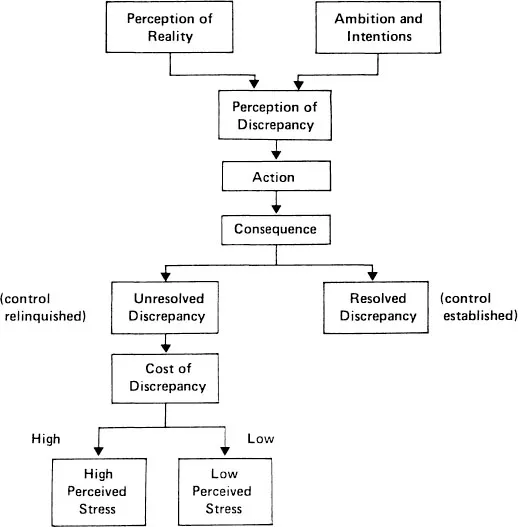

FIG. 1.1 The role of cognitive factors in the definition of stress.

B. A Model of Cognitive Factors in Stress and Control

Figure 1.1 provides a basic conceptualisation of a definition of stress in terms of perceived control over unpleasant environments. This conceptualisation assumes that stress is a change in homeostatic balance resulting in temporary or permanent perceived loss of control. The formulation provided will account for the stressful response to sudden life-threatening or noxious environmental conditions as well as for circumstances where the individual’s own failure creates or exacerbates the pe...