- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chemical and Isotopic Groundwater Hydrology

About this book

This updated and expanded edition provides a thorough understanding of the measurable properties of groundwater systems and the knowledge to apply hydrochemical, geological, isotopic, and dating approaches to their work. This volume includes question and answer discussions for key concepts presented in the text and the basic hydrological, geological, and physical parameters to be observed and measured. Chemical and Isotopic Groundwater Hydrology, Third Edition covers the chemical tools of groundwater hydrology, the isotopic composition of water and groundwater dating by tritum, carbon-14, Cl-36, and He-4, as well as the application of fossil groundwater as a paleoclimatic indicator.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chemical and Isotopic Groundwater Hydrology by Emanuel Mazor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 INTRODUCTION—CHEMICAL AND ISOTOPIC ASPECTS OF HYDROLOGY

1.1 The Concealed Nature of Groundwater

Groundwater is a concealed fluid that can be observed only at intermittent points at springs and in boreholes. Aquifers and flow paths are traditionally deduced by information retrieved from drilling operations, for example, rock cuttings and occasionally cores, but these are poor small-scale representatives of the large systems involved. This feature is familiar to geologists who try to predict the lithological and stratigraphic column to be passed by a new borehole. The outcome reveals time and again a higher spatial complexity and variability than predicted by interpolation of data available from existing boreholes. Prediction of hydraulic barriers, as well as prediction of preferred flow paths, based on knowledge of the regional geology are short-handed as well. Water properties have also been measured traditionally, but they were mostly limited to the depth of the water table, or the hydraulic head, temperature, and salinity. Modern chemical and isotope hydrology encompasses many more parameters and deals with the integrative interpretation of all available data. The concealed nature of groundwater gets gradually exposed.

1.2 Groundwater Composition

Water molecules are built of two elements: hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O). The general formula is H2O. Different varieties of atoms with different masses, called isotopes, are present in water, including light hydrogen, 1H (most common); heavy hydrogen, called deuterium, 2H or D (rare); light oxygen, 16O (common); 17O (very rare); and heavy oxygen, 18O (rare). Thus, several types of water molecules occur, the most important being light, the most common water molecule —and HD16O and heavy, rare water molecules.

The major terrestrial water reservoirs, the oceans, are well mixed and of rather uniform composition. Upon evaporation, an isotopic separation occurs because the light molecules are more readily evaporated. Thus water in clouds is isotopically light compared to ocean water. Upon condensation, heavier water molecules condense more readily, causing a “reversed” fractionation. The degree of isotopic fractionation depends on the ambient temperature and other factors which are discussed in Chapter 9.

Water contains dissolved salts, dissociated into cations (positively charged ions) and anions (negatively charged ions). The most common dissolved cations are sodium (Na+), calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), and potassium (K+). The most common anions are chloride (Cl−), bicarbonate ( ), and sulfate ( ) discussed in section 5.5. The composition of groundwater, that is, the concentration of the different ions, varies over a wide range of values.

Water also contains dissolved gases. A major source is air, contributing nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), and noble gases (Chapter 13)— helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), and xenon (Xe). Other gases, of biogenic origin, are added to the water in the ground, for example, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Biogenic processes may consume the dissolved oxygen.

Cosmic rays interact with the upper atmosphere and produce a variety of radioactive isotopes, three of which are of special hydrological interest: (1) 3H, better known as tritium (T), the heaviest hydrogen isotope, (2) carbon-14 (14C), the heaviest isotope of carbon, and (3) chlorine–36 (36Cl), a rare isotope of chlorine. The rate of radioactive decay is expressed in terms of half-life, that is, the time required for atoms in a given reservoir to decay to half their initial number. The three radioactive isotopes—tritium, 14C, and 36Cl—are incorporated into groundwater. They decay in the saturated zone (section 2.2), providing three semiquantitative dating tools—for periods of a few decades, to 25,000 years, and 105 to 106 years (respectively, sections 10.4, 11.4, and 12.2). The three isotopes also have been produced by nuclear bomb tests, complicating the picture but providing additional information.

Rocks contain uranium and thorium in small concentrations, and their radioactive decay results in the production of radiogenic helium-4 (4He). The helium reaches the groundwater and is dissolved and stored. With time, radiogenic helium is accumulated in groundwater, providing an independent semiquantitative dating method (section 13.9) useful for ages in the range of 104 to 108 years.

1.3 Information Encoded into Water During the Hydrological Cycle

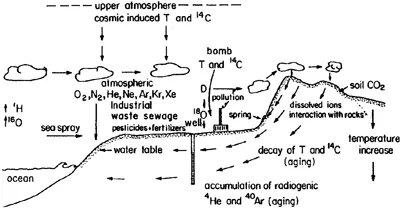

The hydrological cycle is well known in its general outline: ocean water is evaporated, forming clouds that are blown into the continent, where they gradually condense and rain out. On hitting the ground, part of the rain is turned into runoff, flowing back into the ocean, part is returned to the atmosphere by evapotranspiration, and the rest infiltrates and joins groundwater reservoirs, ultimately returning to the ocean as well. Hydrochemical studies reveal an evergrowing amount of information that is encoded into water during this cycle. It is up to the hydrochemist to decipher this information and to translate it into terms usable by water management personal (Fig. 1.1).

Rain-producing air masses are formed over different regions of the oceans, where different ambient temperatures prevail, resulting in different degrees of isotopic fractionation during evaporation and cloud formation. This explains observed variations in the isotopic composition of rains reaching a region from different directions or at different seasons. In terms of this chapter, we can say that water is encoded with isotopic information even in the first stages of the water cycle—cloud formation.

Wind carries water droplets of seawater which dry and form salt grains. These windborne salts, or sea spray, reach the clouds and are carried along with them. Sea spray also reaches the continents as aerosols that settle on surfaces and are washed into the ground by rain.

Rainwater dissolves atmospheric N2 and O2 and the rare gases as well as CO2. In addition, radioactive tritium, 14C, and 36Cl are incorporated into the hydrological cycle and reach groundwater.

Manmade pollutants reach rainwater through the air. The best known is acid rain, which contains sulfur compounds. A large variety of other pollutants of urban life and industry are lifted into the atmosphere and washed down by rain. As clouds move inland or rise up mountains, their water condenses and gradually rains out. Isotopic fractionation increases the deuterium and 18O content of the condensed rain, depleting the concentration of these isotopes in the vapor remaining in the cloud. As the cloud moves on into the continent or up a mountain, the rain produced becomes progressively depleted in the heavy isotopes. Surveys have been developed into a source of information on distance of recharge from the coast and recharge altitude, parameters that help identify recharge areas (sections 9.7 and 9.8).

Upon contact with the soil, rainwater dissolves accumulated sea spray and dust as well as fertilizers and pesticides. Fluid wastes are locally added, providing further tagging of water.

Infiltrating water, passing the soil zone, becomes loaded with CO2 formed in biogenic processes. The water turns into a weak acid that dissolves soil components and rocks. The nature of these dissolution processes varies with soil and rock types, climate, and drainage conditions. Dissolution ceases when ionic saturation is reached, but exchange reactions may continue (section 6.8).

Daily temperature fluctuations are averaged out in most climates at a depth of 40 cm below the surface, and seasonal temperature variations are averaged out at a depth of 10–15 m. At this depth the prevailing temperature is commonly close to the average annual value. Temperature of shallow groundwater equaling that of the rainy season indicates rapid recharge through conduits. In contrast, if the temperature of shallow groundwater equals the average annual temperature, this indicates retardation in the soil and aerated zone until temperature equilibration has been reached. Further along the flow path groundwater gets heated by the geothermal heat gradient, providing information on the depth of circulation or underground storage (sections 4.7–4.9).

Fig. 1.1 Information coded into water along its surface and underground path: right at the beginning, water in clouds is tagged by an enrichment of light hydrogen (1H) and oxygen (16O) isotopes, separated during evaporation. Cloud water equilibrates with the atmosphere, dissolving radioactive tritium (T) and radiocarbon (14C) produced naturally and introduced by nuclear bomb tests. Also, atmospheric gases are dissolved, the most important being oxygen (O2), nitrogen (N2), and the noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe). Gas dissolution is dependent on temperature and altitude (pressure). Sea spray reaches the clouds, along with urban and industrial pollutants. As clouds produce rain, heavy hydrogen (D) and heavy oxygen (18O) isotopes are preferentially enriched, leaving isotopically depleted water in the cloud. Thus inland and in mountainous regions rains of different isotopic compositions are formed. Upon hitting the ground, rainwater dissolves accumulated sea spray aerosols, dust particles, pesticides, and fertilizers. These are carried to rivers or introduced into the ground with infiltrating water. Sewage and industrial wastes are introduced into the ground as well, mixing with groundwater. Underground, water is disconnected from new supplies of tritium and 14C, and the original amounts decay with time. On the other hand, radiogenic helium (4He) and argon (40Ar), produced in rocks, enter the water and accumulate with time. As water enters the soil zone it becomes enriched with soil CO2 produced by biogenic activity, turning the water into an acid that interacts with rocks and introducing dissolved ions into the water. The deeper water circulates, the warmer it gets due to the existing geothermal gradient.

While water is stored underground, the radioactive isotopes of tritium, 14C, and 36C decay and the concentrations left indicate the age of the water. At the same time, radiogenic 4He accumulates, providing another age indicator. A summary of the information encoded into water during its cycle is given in Fig. 1.1.

1.4 Questions Asked

Many stages of the water cycle are described by specific information implanted into surface water and groundwater. Yet, field hydrochemists have limited access to the water, being able to measure and sample it only at single points—wells and springs. Their task is to reconstruct the complete water history. A list of pertinent topics is given below.

1.4.1 Water Quality

Because groundwaters differ from one place to another in the concentration of their dissolved salts and gases, it is obvious that they also differ in quality. Water of high quality (low salt content, good taste) should be saved for drinking, irrigation, and a number of specific industries. Poorer water (more salts, poor taste) may be used, in order of quality, for domestic purposes (other than drinking and cooking), certain types of agricultural applications, stock raising, and industrial consumption. The shorter water resources are, the more important become the management manipulations that make sure each drop of water is used in the best way.

1.4.2 Water Quantity

As with any other commodity, for water the target is “the more, the better.” But, having constructed a well, will we always pump it as much as possible? Not at all. Commonly, a steady supply is required. Therefore, water will be pumped at a reasonable rate so the water table will not drop below the pump inlet and water will flow from the host rocks into the well at a steady rate. Young water is steadily replenished, and with the right pumping rate may be developed into a steady water supply installation. In contrast, pumping old water resembles mining—the amounts are limited. The limitation may be noticed soon or, as in the Great Artesian Basin of Australia, the shortage may be felt only after substantial abstraction, but in such cases the shortage causes severe problems due to local overdevelopment. Knowledge of the age of water is thus essential for groundwater management. The topic of water dating is discussed in Chapters 10– 13.

1.4.3 Hydraulic Interconnections

Does pumping in one well lower the output of an adjacent well? How can we predict? How can we test? Everyone knows that water flows down-gradient, but to what distances is this rule effective? And is the way always clear underground for water to flow in all down-gradient directions? The answers to these questions vary from case to case and therefore a direct tracing investigation is always desired but rarely feasible. Compositional, age, and temperature similarities may confirm hydraulic interconnections between adjacent springs and wells, whereas significant differences may indicate flow discontinuities (sections 2.8, 4.4, and 6.5).

1.4.4 Mixing of Different Groundwater Types

Investigations reveal an increasing number of case studies in which different water types (e.g., of different composition, temperature, and/or age) intermix underground. The hydrochemist has to explore the situation in each study area. We are used to regarding groundwater as being of a single (homog...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Books in Soils, Plants, and the Environment

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- 1 Introduction—Chemical and Isotopic Aspects of Hydrology

- Part I Physical and Geological Concepts

- Part II Chemical Tools of Groundwater Hydrology

- Part III Isotopic Tools of Groundwater Hydrology: Water Identification and Dating

- Part IV Man and Water

- Answers to Exercise Questions

- References