1 Obtaining the metal

The solid matter of the earth’s crust is made up of nearly a hundred elements, the most abundant of which are oxygen, silicon, and then aluminium. So aluminium is the third most common element and in the form of various compounds the metal is very widely distributed. Minute traces of aluminium salts are found in many foods for example, and the element is one of those around which evolution on this planet has developed. Aluminium, unlike some other metals, does not occur naturally in its pure metallic form. Only certain of the multitude of aluminium-bearing minerals may be regarded as ores, since extraction from many of them is currently too uneconomical. Commercial ores are grouped under the generic term ‘bauxite’, derived from the medieval village of Les Baux in Southern France, where high concentrations of hydrated aluminium oxide are found, and where early mining of the ore took place.

There are widespread sources of bauxite throughout the world, including in addition to Les Baux, Greece, Hungary, Jamaica, Africa, the USA, Australia and South America. It is a metal in plentiful supply.

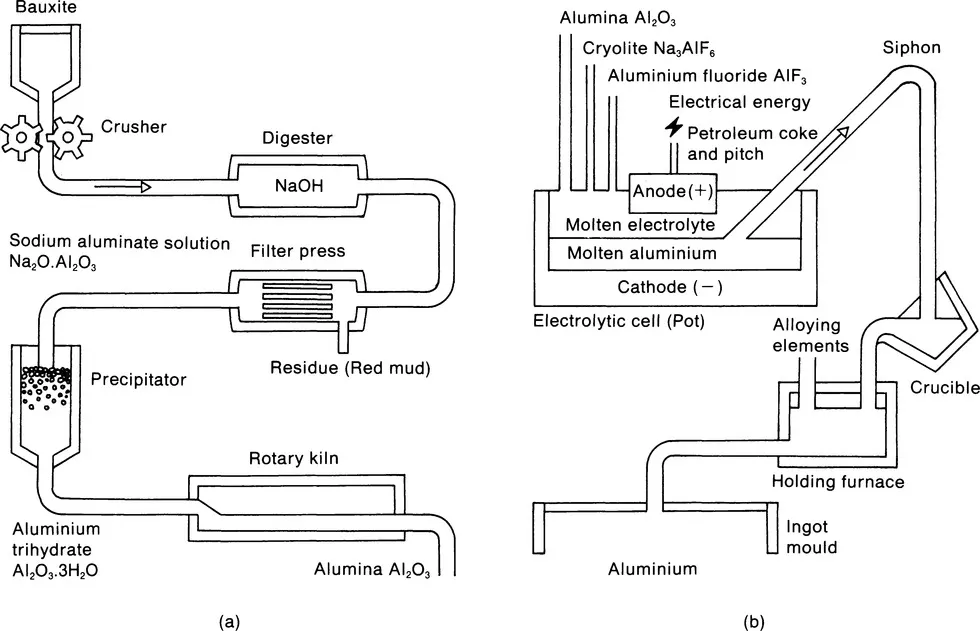

The reduction of bauxite to metal involves two main operations. First the bauxite is treated chemically to remove impurities and obtain aluminium oxide, alumina (Figure 1.1(a)). Then using the Hall-Héroult electrolysis process the alumina is reduced to aluminium, that is to say, the oxygen is removed. The basic process discovered by Hall and Héroult is still the one used today, although refinements in the techniques used have resulted in much more power-efficient operations. The process involves a bath of fused cryolite containing dissolved alumina which is electrolysed by the passage of a high amperage, low voltage current between carbon anodes and the carbon lining of the cell, which forms the cathode. The alumina is decomposed into oxygen and aluminium. The former is liberated at the anodes and the pure aluminium sinks to the bottom of the cell from where it is tapped off periodically and cast ready for further treatment (Figure 1.1(b)). The production process operates with many of these electrolytic cells being connected in series of lines (known as pot lines) of up to 150 in number. Continuous operation is maintained as a necessity to avoid the cooling down and subsequent solidifying of the baths.

Mining of bauxite takes place in many parts of the world

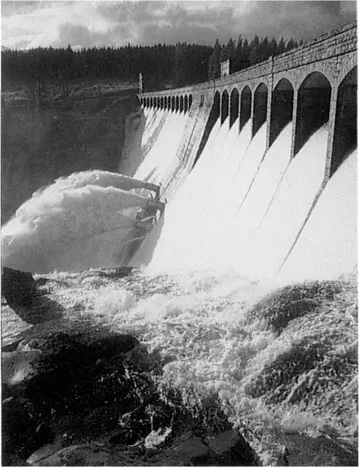

Cheap electrical power is the key to the production of low-price, high-grade aluminium. Hydroelectric power was the obvious first source, and the aluminium industry has its origins in areas like Switzerland, Scotland, Canada and Norway where water power was available in abundance to be harnessed for the production of electricity.

Today, hydropower remains a major source of electricity for aluminium extraction, and one which is completely acceptable environmentally, while in addition coal, natural gas and nuclear energy are also utilized. In the UK for example, there are smelters operating using electricity generated from hydropower, coal, and nuclear energy.

Figure 1.1 From bauxite to aluminium: (a) stage 1 - the chemical process; (b) stage 2 - the electrolytic process

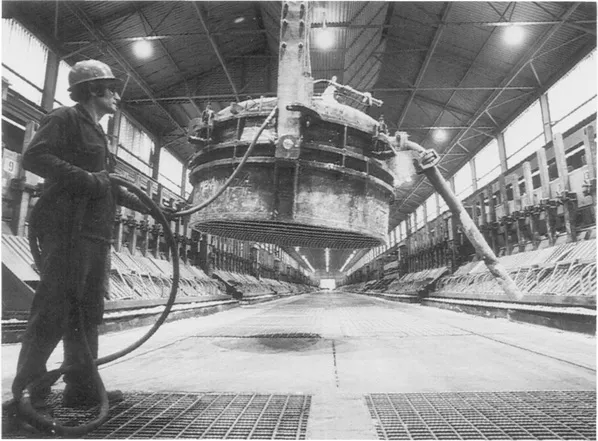

General view inside an aluminium smelter showing the lines of ‘pots’ in which the alumina (aluminium oxide) is turned into pure aluminium

Hydroelectric power has been used in the Scottish highlands by British Alean since 1894. The Laggan dam, seen here, is part of a project that feeds water to British Alcan’s Lochab er power station at the foot of Ben Nevis. First opened in 1929 the power station supplies the adjacent Lochaber smelter, which produces around 40 000 tonnes of aluminium annually

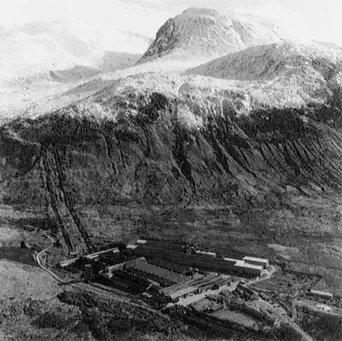

The Lochaber smelter of British Alean at the foot of Ben Nevis. The pipes carrying the water down the mountainside to the power station are clearly visible

2 Properties of the metal

Aluminium’s unique properties have set the metal apart as a special building material exhibiting outstanding properties: strength, lightness, durability and versatility. There are many other properties of aluminium that make it particularly suitable for specific applications outside building - its electrical properties make the metal ideal for busbar and overhead cables; its heat conductivity makes it ideal for car radiators and hollow-ware; its malleability and compatibility with foodstuffs provide many uses in packaging, and its surface treatment characteristics make aluminium the major material for lithographic printing plates. But in the construction industry it is the combination of strength and light weight, the high natural resistance to atmospheric attack, and the ease with which the metal can be formed that have led to such a wide range of vastly different uses for aluminium in building.

Additionally the ease with which the metal’s surface can be treated in various ways to provide a range of decorative and protective finishes adds to aluminium’s list of advantages.

Alloys

Up to this point reference has been made only to ‘pure aluminium’ and ‘the metal’. In fact the term ‘aluminium’ is widely used generically to encompass a whole family of alloys – each with its own specific properties and applications.

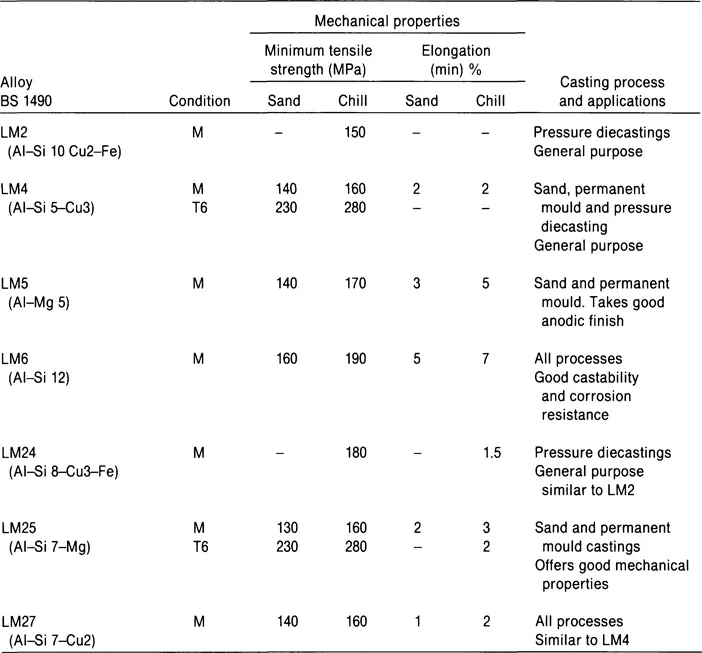

Table 2.1 Properties of some typical casting alloys used in building

Pure aluminium easily alloys with many other elements. Among these, magnesium, silicon, manganese, copper and iron are regularly used. More recently lithium has been added to the range providing alloys of much higher strength and lower density than any of the traditional alloys. These Al-lithium alloys are of particular value for the aircraft industry but are not expected to be used for general engineering applications owing to their high cost of production.

Alloy classification

Aluminium and its alloys are divided into two broad classes, cast and wrought. The latter class is subdivided into non heat-treatable and heat-treatable alloys. In the non heat-treatable group, properties are altered by the degree of cold-working that is performed, such as rolling. In the heat-treatable group, strength is affected by the application of various heat-treatments.

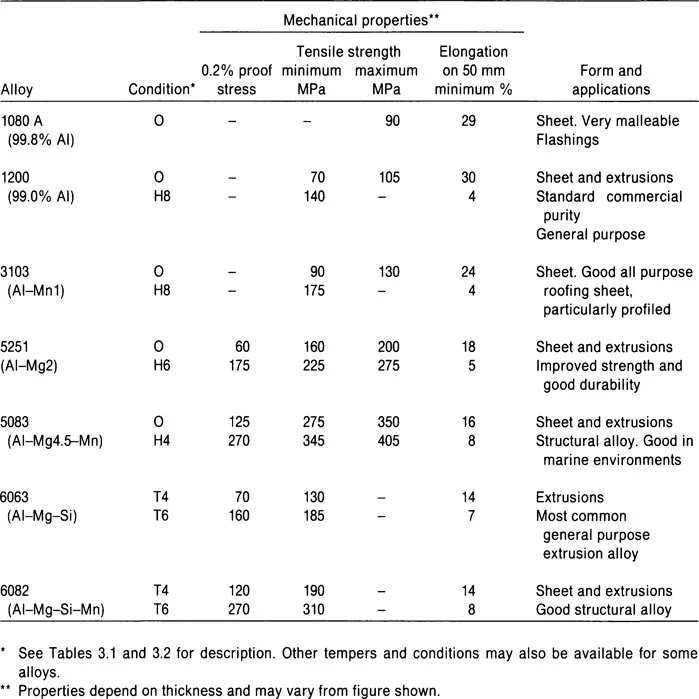

Table 2.2 Properties of some typical wrought alloys used in building

Some casting alloys are also strengthened by heat-treatment.

Alloy designations

Castings

Casting alloys for general engineering applications are specified in BS 1490, aluminium alloy ingots and castings. They are numbered from 0 to 30 and prefixed with the letters LM (originally meaning light metal). Not all of the numbers in the sequence are now in use. Various suffixes are also employed to indicate the condition or heat-treatment condition of the alloy.

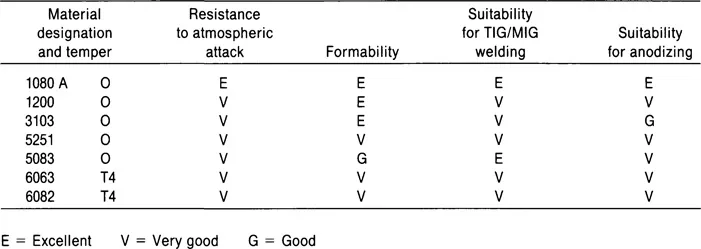

Table 2.3 Typical characteristics and processing suitability of typical wrought alloys

Wrought

Wrought alloys are specified by a series of British Standard specifications. They are classified by chemical composition in an internationally agreed four-digit coding system. The first of the four digits indicates the alloy group as decided by the major alloying elements included, and are as follows:

The remaining three digits are available to indicate alloy modifications.

Wrought alloys are further subdivided into non heat-treatable (that is work-hardening) and heat-treatable alloys.

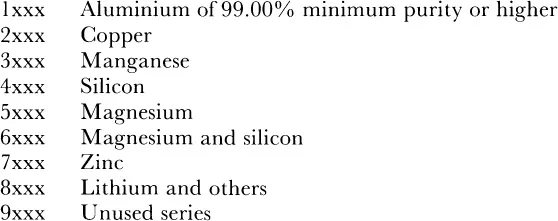

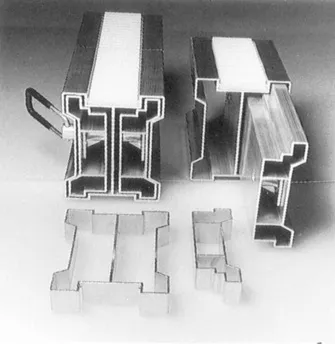

This light-weight access platform utilizes two specially designed telescopic sections. The system is easily transported, assembled and dismantled (courtesy Sky winder)

Close-up of the two main telescopic hollow sections used in the Skywinder access platform

Specific properties

Weight

Pure aluminium is one of the lighter elements with a density of 2.7 g/cm3 (0.098 lb/in3). The densities of its alloys vary, most of them fall within the relatively narrow band of 2.63-2.80 g/cm3, while the lithium-based alloys have a density of around 2.55 g/cm3.

Those alloys with densities lower than that of pure aluminium, apart from the lithium ones, are those in the Al-Mg series, due to magnesium being lighter than aluminium.

Strength and ductility

As a very rough guide, strength and ductility are inversely proportional. When one is high the other is low. Where severe forming is to be carried out, for example on a roof flashing, then the material being used (for example commercial-purity sheet) should be specified in the soft, ductile condition designated by the alloy suffix Ό’.

Testing a metal sample for its tensile properties

Tensile strength is not significantly affected by temperature fluctuations in atmo...