![]()

1

Geopolitical Focus on Southern Africa

South Africa is the dominant force in a region of the world that is of increasing strategic importance to the West. Yet most studies of the region concentrate on the social and cultural aspects of the South African crisis and only rarely address the geopolitical pressures that dictate the course of political events. This book takes a regional approach to the issue of South Africa and its geopolitical power in Southern Africa and in so doing brings a unique geographical perspective to the debate over what U.S. foreign policy toward the region should be. Going beyond the issue of apartheid we examine the less familiar, but critical patterns of geographic and economic forces, which to a substantial degree determine the locus of power in the region and serve as the underpinnings for South Africa’s regional dominance. By examining these forces we explain how South Africa established hegemony over the region, how it maintains its preeminence, and why it holds the key to the political and economic future of Southern Africa. Our objective is to define clearly the decisive role South Africa plays in the region and, within the context of economic interdependence, to understand how the United States might formulate a successful foreign policy for Southern Africa.

U.S. foreign policy attention has shifted to Southern Africa; such attention is long overdue. This focus, however should not be so narrow as to rest exclusively upon the transient issue of apartheid. Although significant for any number of political reasons, the demise of apartheid and removal of the white regime in Pretoria are but a part in the process of seeking solutions to the region’s multifaceted problems. The United States should balance its immediate policy objectives with consideration of the long-term issues that will endure well beyond any white regime and challenge the leadership of whomever holds power. The patterns of pluralism and poverty that underlie the current black-white struggle for power will remain largely intact. The Southern African region is one where internal economic and political instability are chronic problems that defy short-term solutions. Globally, the significant factors of Western dependence on the region’s large concentrations of strategic minerals and location of the Western world’s most important petroleum supply line, as well as the presence of large numbers of East Bloc forces, has elevated the region to an area of potential superpower confrontation. The ongoing political instability of the region threatens the national security interests of the West and presents an open invitation to Soviet adventurism. The resulting focus of superpower competition on Southern Africa is itself exacerbating the economic and political instability of the region and complicating the process of managing global rivalry. Many of these critical issues have not been fully developed by those addressing the South African problem. By taking a regional approach we bring new issues to the debate and seek to make a constructive contribution to the question of what U.S. foreign policy should be.

The Emphasis on Apartheid

For the past two years the Republic of South Africa has been in the spotlight of Western media attention. The focus of this attention is the social system of apartheid, by which the white South African government currently maintains economic and political dominance over other, more populous South African ethnic groups. Ephemeral in nature and similar to racial discrimination occurring elsewhere, apartheid, by virtue of its codified nature, colonial trappings and the involvement of whites, has, nevertheless, obscured the larger, fundamentally more important problems that menace the future of Southern Africa and the fact that the states of the entire region are inextricably dependent upon one another, economically and politically. Any policy or action, therefore, which the United States undertakes toward the Republic of South Africa will have an impact not just on it but also, in quantifiable terms, upon numerous other nations within this region. U.S. policies thus touch the lives not of millions but of many tens of millions of Africans. Policies of this magnitude must be based upon more than just an American historical perspective on race relations.

It is in the long-term self-interest of all actors in the conflict to seek an end to apartheid and the inclusion of all ethnic groups in the governance of South Africa. There will be no lasting peace within the country until this occurs. Nkrumah’s assertion that no African country would be truly independent until all were independent is still widely accepted, and the importance to other Africans of ending the white domination of South Africa must be recognized. It is, however, also in the best interest of all concerned that the transition to majority rule not be accomplished in such a way as to undermine the economy of South Africa. To do so would jeopardize the future of the entire region of Southern Africa and bequeath to those survivors of the transition process a country without the economic growth potential necessary to prevent debilitating competition for economic resources and with high unemployment, conflict between ethnic groups and, ultimately, a loss of confidence in any new government. A black-governed South Africa will face the same problems experienced by its white predecessors and almost all other African countries: a high rate of population growth and unemployment, a resource-based economy highly sensitive to downturns in the world economy, the overcrowding of major urban areas as unemployed workers migrate from the rural areas, and the co-existence of numerous ethnic groups with a history of violent competition for power and resources.

The future governments of South Africa will need to use every available resource to address these long-term problems successfully. Chief among these is a strong, expanding economy. Economic growth can create a strong black middle class and prevent an explosion in the unemployment rate, especially among youths, that would otherwise promote violent ethnic conflict and threaten the legitimacy of the government. It is well accepted that the impetus for the ongoing transition of power in South Africa will come from within. Neither increased U.S. investment in South Africa nor the adherence of Western multinational corporations (MNCs) to the Sullivan Code will influence the rate at which the South African regime divests itself of power. Nor will economic sanctions and widespread disinvestment bring an end to apartheid.

Sanctions and disinvestment could, however, constrain economic growth and, as a result, greatly reduce the capabilities of future black governments to satisfy the demands of their constituents, severely penalize the economies of other African states, and ultimately threaten U.S. foreign policy objectives in the region. The U.S. should distance itself morally from Pretoria and exert pressure where feasible both to encourage the South African majority struggling for power and to induce white South Africans who identify with the U.S. to reexamine their support for apartheid. The United States does not, however, have any meaningful leverage over South Africa. Implementing policies designed to punish the intransigent white regime out of frustration is unwise, as it runs the risk of injuring those it wishes to help and creating an unstable political and economic environment in which Soviet adventurism may flourish.

Interdependence

The elements most crucial to the determination of South Africa’s regional power are geographical and economic in nature. When examined within the framework of interdependence, they are easily understood and present clear guidelines concerning which regional policy options have the promise of success and which do not. Accordingly, we have structured this book to take advantage of the explanatory capabilities of interdependence.

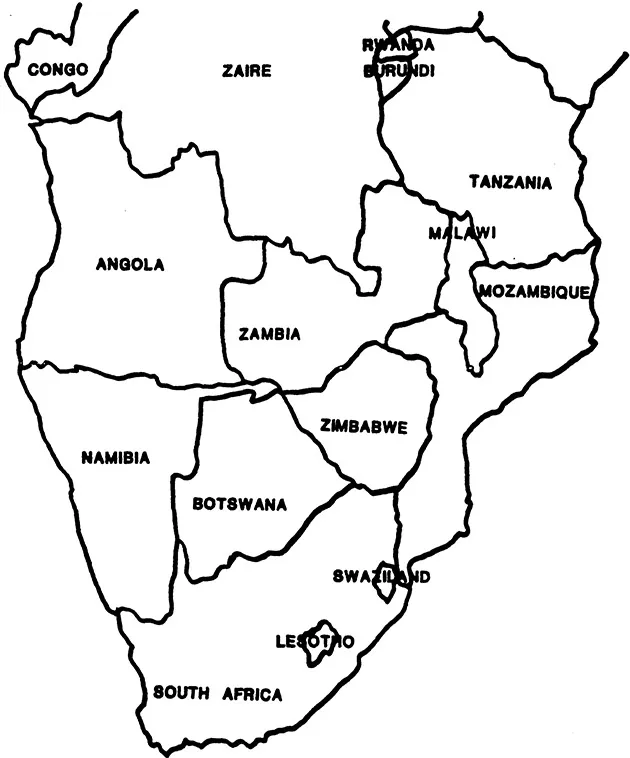

The region of Southern Africa is united by its transport infrastructure. Geographers refer to this phenomenon as a functional region, that is, an area organized around a particular function. In this case, it is a transport network, the tentacles of which carry trade and economic benefits across state boundaries to bind the region together in the performance of the transport function. Typically there exists a core area that serves as the hub for the activities of the functional region, which is united by lines of communication to lesser nodes of activity located in the hinterland. The core area generally dominates the hierarchy of nodes. Southern Africa may be viewed as a functional region defined by a rail transport system that extends from Cape Town as far north as Zaire. The core area of this rail network is South Africa (with three-quarters of the railway mileage), from which the threads of railway extend northward to bind Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia and Zaire.

Political scientists, recognizing the existence of functional regions, have analyzed these patterns of communication when studying systems of interdependence. Their goal is to determine the implications of the increased interaction between states vis-a-vis these functional systems for understanding the behavior of states. While some approaches emphasize the quantity and typology of interactions between nations, the most useful approaches deal with the impact of international events on the domestic sector. The exponential growth of technology, trade, and communications creat a milieu in which the state is no longer an economic unit, but is in fact economically interdependent with other states. Thus, the decisions or transactions of one state no longer affect it alone, but might in fact result in reciprocal costs to other states. Interaction between states where reciprocal costs occurred, it is argued, constitutes a situation of interdependence.

The models and concepts of interdependence and their contribution to one’s understanding of state behavior are best elucidated in Keohane and Nye’s text, Power and Interdependence. According to the authors, there is rarely a situation of symmetrical interdependence where the costs to country A of decisions made by country B equal the costs to country B of decisions made by country A. Most interdependent relationships are asymmetrical, with one country less dependent upon the other. The less dependent country has leverage over the other country by virtue of its ability to inflict greater costs. The susceptibility of a country to the costs of decisions made externally is known as its sensitivity. A country may, however, change its policies in order to reduce its sensitivity and thus minimize the impact of these costs. A country’s susceptibility to suffer externally imposed costs after the implementation of such policy changes is known as its vulnerability.1

The interdependence model has great relevance for our understanding the behavior of states in Southern Africa. The interest of the superpowers in that region reflects, to a significant degree, the fact of interdependence. This interdependence, however, exists not only at the global level but characterizes the relationships between the countries of the region of Southern Africa as well. Understanding the role South Africa plays in sustaining these two levels of economic interdependence is essential to the successful formulation of policy or the evaluation of policy options for the region.

Figure 1-1 Southern Africa

At the global level the West is dependent upon South Africa because of its strategic position upon the major oil transport route from the Middle East and the strategic minerals that are produced in or shipped through South Africa. The West, by virtue of its dependence upon Africa’s minerals, is vulnerable to decisions made by South Africa. These decisions can directly determine whether the United States or its allies receive these strategic minerals. Moreover, South Africa’s substantial regional power enables it to control the outcome of events within Southern Africa -- events, for example, directly related to the achievement of Western foreign policy objectives. Western policy makers are clearly aware of South Africa’s veto power over their regional African strategies concerning the geopolitical issues previously discussed. The U.S. policy of “constructive engagement” would appear to reflect an understanding of this fact. When the West has sought to impose costs upon South Africa, Pretoria has effected policy changes that have substantially reduced its sensitivity. South Africa’s development of its synfuels program, uranium enrichment plant and arms industry are but three successful examples of sensitivity reduction. The future may witness an erosion of South Africa’s superior position in the context of global interdependence, but the past two decades have demonstrated that in its interdependent relationship with the West, South Africa is the less dependent.

At the regional level, South Africa enjoys substantial power and influence as a result of its decidedly asymmetrical interdependence with its neighbors. South Africa’s control of the region’s transport network and its ability and willingness to exert military influence with either conventional or surrogate forces has rendered the countries of the region vulnerable to decisions made in Pretoria. In fact, the degree to which the region is explicitly vulnerable serves to enhance South Africa’s leverage in its more balanced interdependent relationship with the West.

South African Hegemony

South Africa is the regional power of Southern Africa. The economy of South Africa dwarfs those of other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The South African economy is highly diversified, technologically advanced, and capable of internally generating substantial amounts of investment capital. It accounts for nearly 80 percent of the region’s total gross national product, as well as over 70 percent of corn, wheat and electrical production, and provides legal employment for 350,000 workers from neighboring countries. Foreign workers living illegally in South Africa are estimated to exceed 1 million. South Africa also provides a substantial market for regional manufactured goods and handles most of the regional import/export trade through its modern, efficient port system. In addition, South African MNCs are well established throughout the region, providing managerial expertise, technology and investment capital to industries that are, in some cases, the chief foreign exchange earners in their country. As dominant as South Africa is economically, militarily its power is even more significant.

South Africa’s foreign policy objectives in the region call for destabilizing neighboring states that have the potential to threaten its security. The ability to project a strong military presence is seen as essential to accomplishing these objectives and preserving white political control. South Africa has achieved this capacity by retaining strategic terrain, sponsoring surrogate military forces and developing a powerful defense force. Control of Namibia provides South Africa with a major port (Walvis Bay), 700 miles north of Saldanha Bay, from which military operations can be initiated against coastal targets as far north as Angola’s Cabinda enclave. In addition, military bases and airstrips in northern Namibia and the Kaprivi Strip give Pretoria the strategic locations from which it may project its military power into Angola, Zambia, northern Botswana and Zimbabwe. It was the presence of South African air support that halted the mechanized assault by the Soviet-led Movement for the Popular Liberation of Angola (MPLA) that threatened to reach the headquarters of the Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) at Jamba in the fall of 1985. South Africa has used surrogate forces effectively. Its support for guerrilla movements in Mozambique and Angola has negated any possibility of those governments unifying the former Portuguese colonies or organizing them into staging areas for attacks against South Africa. Zimbabwe also claims that South Africa is supporting elements of “Super-ZAPU,” the Ndebele dissident group, and was behind the raid on the Thornhill Air Force Base that destroyed much of Zimbabwe’s air force.

South Africa does not depend on surrogates to the neglect of its own military capabilities. The South African Defense Force (SADF) is the largest military force in sub-Saharan Africa, with a total available personnel strength (including reserve components) approaching one-half million men. The SADF is well trained and motivated with substantial combat experience accruing from its lengthy tenure on the Angolan border. Many of its weapons are high quality, domestically produced arms manufactured by Armscor. Though somewhat lacking in fighter aircraft, the SADF is more than a match for the combined forces of the neighboring states, including the Cuban combat forces in Angola. In addition to conventional forces, Pretoria may possess nuclear weapons. Speculation by a number of authors suggests that South Africa has developed nuclear arms.2 Whether or not this is the case, the possibility increases the respect with which one must regard South Africa’s military capabilities.

South Africa underscores its regional hegemony by a willingness to use both economic and military strength in a carrot-and-stick style of regional foreign policy. Condemned by the West and subject to its sanctions and ideologically opposed to the East, South Africa recognizes its isolation and does not believe that failing to take action against a neighboring state will improve its standing among Western powers. Like the Israelis, whom they much admire, South Africa disregards criticism and behaves in a fashion calculated to achieve its own domestic and regional objectives. The use of import blockades and pre-emptive military attacks on Botswana, Lesotho, Angola, and Mozambique send a clear signal to other countries in the region of South Africa’s willingness to use its superior military and economic power to achieve its regional policy objectives.

In point of fact, South Africa dominates the states of the region. Countries as far north as Zaire are dependent upon South Africa, vulnerable as a result, and demonstrably willing to evaluate South Africa’s position on an issue of substance before initiating action. International powers must also be cognizant of Pretoria’s regional dominance and its ability to deny them foreign policy success. South Africa’s regional hegemony complicates the ability of the superpowers to manage their rivalry in an area of the world that is of increasing geopolitical importance to the West.

Geopolitical Focus

Of all non-fuel minerals, the four considered strategically most important to the West are chromium, cobalt, platinum, and manganese. They are essential to the economies and defense sectors of the industrialized countries. Steel cannot be made without the purifying properties of manganese. Chromium and cobalt are critical components in high-strength alloys used in the most sophisticated defense technologies, while platinum is used extensively in petroleum refining and communications. Because economically recoverable reserves of these minerals are not found in the United States, Europe, or Japan, the industrialized West is virtually 100 percent dependent upon foreign sources for them. Most of the non-communist world’s reserves of these minerals are concentrated in Southern Africa. Alternative source...