![]() Part I Introduction

Part I Introduction![]()

1 Everyday physics and conceptual structure

This book is intended as a contribution to cognitive psychology and educational practice.Nevertheless, it would not have been written had it not been for a simple fact of modern life, that many students experience school physics as extremely unpleasant. Indeed, many students regard school physics as a painful ordeal whose only saving grace is that it can be quickly jettisoned in favour of the humanities or the biological sciences. Thus, even amongst A-level candidates, who are themselves a selective sample, only about one-sixth of students are currently enrolled in physics.1 This rejection of school physics led to the book because of the discussion about what lies behind it, discussion in other words of why physics proves such a nightmare that so many students wish to abandon it at the first opportunity. The discussion has been wide-ranging for there is considerable anxiety about our nation’s competitiveness when such a central science is being shunned, and over the years a range of proposals have been made. One favourite is poor teaching. It is argued that when physicists are so rare and so valuable, the good and inspirational ones are unlikely to be attracted to a low-paid profession like teaching. Another is to call on the nature of physics. It is said to be too mathematical or, with phrases like ‘a massless rope strung over a frictionless pulley’, too abstract.

Such claims may or may not have relevance. However no matter what their truth, they have been supplemented in recent years by a different approach, and this is what triggered the book. Instead of focusing on the teaching or the subject matter, the new approach draws attention to the students themselves. It is centred on the proposal that when students embark on physics, they are not ‘blank slates’ with respect to the phenomena they will be studying. Rather, they are holders of strong preformed ideas which, being at variance with the received wisdom of science, lead to faulty representations during problem solving and hence to failure and eventual frustration. These preformed ideas are frequently referred to as ‘everyday physics’. To support the approach, there has been a stream of studies charting the behaviour of novice students of physics while they work on typical problems, and there is little doubt that these studies do attest to preformed ideas which are deeply engrained and educationally subversive. However, while this must be recognised, it does not necessarily mean that everyday physics is the extreme polar opposite of received science wisdom. On the contrary, points of contact are not simply possible but can in fact be readily observed. It is this paradoxical combination of similarity within difference which renders everyday physics psychologically and educationally interesting and which prompted the book.

This chapter and its successor will set the scene for what is to follow in the book’s main body by explaining why everyday physics is significant from the psychological and educational perspectives. To begin, this chapter will summarise a sample of studies with novice students of physics which leaves few grounds for doubting that preformed ideas do play a role in problem solving and that the consequence of this often turns out to be problem-solving failure. The chapter will then show how, despite this, preformed ideas are not in all respects ‘at variance’ with received science wisdom, by virtue in fact of identifying three points of contact between everyday and received ideas. The first is that the everyday system often makes reference to variables, some of which are scientifically relevant. In other words, relations of the ‘If Condition Ci then Event Ei’ form are used and in some cases the conditions are not too wide of the mark. For example, many novice physicists believe that if objects are metal, they will heat up relatively quickly. This belief is in fact correct. The second point of contact is that the everyday system often calls upon causal mechanisms, and these mechanisms can also contain elements of truth. For instance, a downwards force akin to gravity is frequently recognised, even if this force is taken to operate in an unorthodox fashion. The final point of contact is that the posited relation between variables and mechanisms is in some cases suggestive of theorising. This is to say that, as with a theory, the mechanisms play a generative role in the selection of variables. Thus, it is because heat works in a particular way that metalness is seen as significant to the rate of heating. It is because of the workings of gravity that certain variables are seen as significant to resting or falling.

Having identified these points of contact, the chapter will then begin the task of explaining why they give everyday physics its great significance. Its first step here will be to show how the points of contact concur exactly with the predictions of a recent and influential approach within cognitive psychology. The approach centres on the claim that the generative power of mechanisms is no more and no less than a ‘primitive’ of human cognition, with theoretical structure being as a consequence an entrenched feature from early in life. This being the case, there is a strong expectation that theoretical structure will be identifiable in mechanism-variable relations, meaning that the third point of contact is supportive evidence. In addition though, understanding mechanisms will clearly, on this approach, have the force of a cognitive imperative and this imperative will also operate from early in life. However, given the structuring of physics education in the industrialised world, novice students are typically teenage or older. Thus, they will have had plenty of time to respond to the imperative, and should have attained a fair understanding. As a result, there is an expectation of some orthodoxy over mechanisms, meaning that the second point of contact also supports the approach.

In addition though, to the extent that the approach is endorsed, so the teaching problems engendered by everyday physics become less severe than they superficially seem. After all, if variables are generated by mechanisms, the implication is that teachers should focus their attention upon the latter. The links and contrasts between the mechanisms of everyday and professional physics should be mapped out carefully, and strategies should be developed for fostering orthodoxy. If this were done, orthodoxy over variables should fall out naturally. In addition though, the partial adequacy of mechanisms means that fostering adequacy may not prove particularly difficult. Thus, if the approach just outlined is correct, there are also strong and positive implications for educational practice, meaning that the findings from everyday physics are beginning to seem like very good news indeed.

However, is this sense of endorsement really justified? For one thing, does the approach to cognitive psychology require empirical support from everyday physics? Has it not become established already with reference to other evidence or perhaps to logical necessity? Moreover, even if further evidence is required, can the findings from everyday physics be regarded as conclusive? The present chapter will end by raising these questions, to see them discussed further in Chapter 2. The answers across the two chapters will be ‘Yes, empirical evidence is required’, but ‘No, the evidence from everyday physics is not conclusive’. Rather, the evidence has established everyday physics as a key arena for further research. Indeed, the required research should not simply bear incisively upon the aforementioned approach and its educational ramifications; it should also resolve core issues about cognition in general. As Chapter 2 will make clear, the research in question will be developmental, tracing changes with age with regard to variables, mechanisms and their interrelation. This then is where the present chapter is heading, towards the acceptance that the similarities yet differences between everyday physics and science orthodoxy make the former an arena for developmental research of some significance. The results of such research will occupy us from Chapter 3 onwards.

THE ‘ALTERNATIVENESS’ OF EVERYDAY PHYSICS

The emphasis will, then, be on the development of the preformed ideas that are eventually brought to physics, the development in other words of an everyday physics. However, to put the enterprise in context, we need, as signalled already, to look at everyday physics at the point of formal instruction. Does it really show the ‘alternativeness’ which many have claimed, and yet does it also show the points of contact which render it significant? To answer the question, the present section will summarise a sample of the studies mentioned already. These are studies which take school pupils or college students who have recently embarked on the study of physics and chart the strategies which they use while working through a characteristic series of problems. For clarity, the section will organise the studies into two subsets: those concerned with predictive problem solving and those concerned with explanatory. Having reviewed the studies, the section will make comparisons with science orthodoxy. Is everyday physics an alternative and subversive entity which nevertheless shares some properties with received ideas? Moreover, what does this paradox signal for theory and practice?

Predictive problem solving

A favoured approach to physics teaching is to present students with constellations of variables and ask them to predict outcomes from given values. Empirical problems of this kind are used, as for example when students are asked to predict the temperature loss per unit time of water which is presented to them in containers of varying material. However, theoretical equivalents are also popular when for example students are told that an object falls from a particular height, and asked to calculate its speed on landing. Many research projects have assessed students’ success and failure on these kinds of problems. Indeed, there have been cross-nation surveys to this effect. However in their own right, such projects have little to say about the existence of everyday physics. Whatever else is involved, obtaining the correct answer is at least partly a function of computational skill. Thus, by simply looking at success or failure, it is impossible to differentiate the effects of preformed ideas from the effects of mathematics.

Greater insight might be obtained by looking at the general direction of solutions rather than bothering about their accuracy in detail. Thus, the issue in our empirical example would be whether greater temperature loss is predicted in, say, a metal container than a polystyrene one. Whether the absolute value was correct or not would be beside the point. The issue in the theoretical example would be whether landing speed is predicted to be greater than, equal to or less than starting speed, again regardless of computational accuracy. However while this more global analysis would undoubtedly be preferable, there is still potential ambiguity about the inferences to draw. Guessed solutions would, in some circumstances, be hard to differentiate from those motivated by preformed ideas. Thus, an even better method would be to combine global analysis with students’ accounts of what their predictions are based on. In cognitive science, the traditional approach to obtaining accounts of any problem-solving activity is to ask students to ‘think aloud’ while performing the task. However, an alternative approach which is equally immediate and surely more natural is to question students directly as to why they responded in the way they did.

Taking predictions plus follow-up questioning as the preferred approach, there are a number of relevant studies. However, although these studies have covered a range of topic areas, two themes recur and thus provide particularly convincing evidence on the issues at stake. The first theme is object fall after horizontal motion, as for example when a ball rolls off a cliff or an apple core is tossed from a moving car. In these circumstances, the object will fall following a parabolic path in the direction of the horizontal motion. This results from the interplay of the progressive deceleration in the horizontal direction and, due to the force of gravity, the progressive acceleration in the vertical. It is, importantly, nothing to do with the dissipation of a horizontal force, for there are no forces in that direction subsequent to the object being set in motion. The question that most of the studies have addressed is whether students appreciate this point.

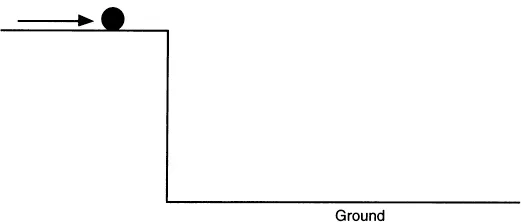

The first, and best known, of the studies was conducted by Michael McCloskey and various colleagues and is summarised in McCloskey (1983a). The study was part of an ambitious programme of research, utilising a range of problems within the basic paradigm, for instance metal balls dropped from an aeroplane or, as in Figure 1.1, sliding over a cliff. In much of the research, students were simply asked to predict the paths that the objects would follow. This established that forwards parabola are correctly anticipated in fewer than 50 per cent of the cases, with the errors including backwards parabola, vertical straight lines, diagonal straight lines and horizontal straight lines followed by downwards paths of varying shapes. The study of interest also involved prediction and replicated the basic results. However in this study, the prediction phase was followed by interviews where students were asked to explain their responses. Thirteen students were interviewed, all undergraduates with limited expertise in physics. Eleven showed strong commitment to a gradually dissipating horizontal force, indicative as McCloskey points out to a concept of ‘impetus’.

Similar results were obtained by Aguirre (1988) in a study with 15- to 17-year-old pupils. Aguirre’s apparatus was a large flat surface positioned at an angle to the floor. There was a plunger in the top left hand corner which could propel a plastic block onto the surface. With horizontal velocity under the influence of gravity, the block’s path would be parabolic. However as with McCloskey’s study, the pupils seldom appreciated this, making a similar array of inaccurate predictions. Moreover, in justifying their predictions, the pupils frequently cited a horizontal force akin to impetus. Other studies, for example Whitaker (1983), produce similar results, but there are also subtle differences. One appears in the work of Eckstein and Shemesh (1989) on descent from a moving vehicle, in this case a cart. Adult and child novices in physics were asked whether (and why) a ball falling from a pole attached to the cart would land in a cup placed directly below. Two groups were identified in terms of response. One group answered incorrectly that the ball would miss the cup, usually calling on impetus. The other group by contrast answered correctly that the ball would land in the cup but justified this with reference to a quasi-magnetic relation between ball and cart. As one respondent put it The ball is like one unit with the cart and the post. It’s all one body’(Eckstein and Shemesh, 1989:330).

Figure 1.1 An example of the problems used by McCloskey (1983a)

The diagram shows a side view of a cliff. The top of the cliff is frictionless (in other words, perfectly smooth). A metal ball is sliding along the top of the cliff at a constant speed of 50 miles per hour. Draw the path the ball will follow after it goes over the edge of the cliff. Ignore air resistance.

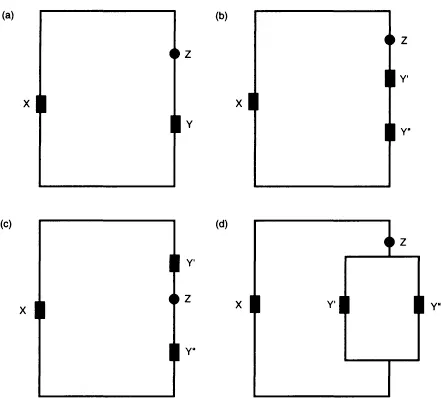

The ‘one-ness’ reported by Eckstein and Shemesh is not the same as the impetus reported by McCloskey and Aguirre. Nevertheless, they both amount to data which are grist for our mill, for they both bear witness to ideas that are unlikely to have come from orthodox science. They do however relate to a single theme. Thus, it is as well that, as mentioned earlier, there is parallel and equally voluminous research on a different theme. The theme is electricity, and in particular the consequences of differing arrangements of resistors and batteries. To appreciate the issues, consider Figure 1.2 which depicts some possible, but very simple, electrical circuits. Imagine for the moment that X refers to a battery, Y, Y’ and Y” to identical resistors, and Z to an indicator of current (perhaps nothing more than a light bulb). In these circumstances, (a) has one resistor while (b) and (c) have two connected in series. In both cases, the consequence would be to decrease the current relative to (a). Although (d) also has two resistors, they are connected in parallel. The consequence here would be to increase the current relative to (a). If by contrast X referred to a resistor and Y, Y’ and Y” to identical batteries, the consequence of (b) and (c) would be to increase the current relative to (a). The consequence of (d) would be to maintain the current of (a).

A number of studies have used circuits along the lines of Figure 1.2 to explore everyday physics. One such study was reported by Gentner and Gentner (1983). Here thirty-six high school and college students ‘screened to be fairly naive about physical science’ (Gentner and Gentner, 1983: 117) were asked to predict the current in circuits like (a), (b) and (d), with doubling of the resistors in some problems and doubling of the batteries in others. The students were also quizzed about their ‘mental models’ as to how electricity travels. Gentner and Gentner identified two main models labelled, in a fairly self-explanatory fashion, the ‘water flow’ and the ‘moving crowd’. They hypothesised that students who subscribed to the water flow model would perform well when the batteries were doubled. This is because the serial set up, that is (b), should remind them of tanks at different heights, height being the sole consideration relevant to water pressure. The parallel set up, that is (d), should remind them of tanks at the same height where water pressure is therefore identical. Gentner and Gentner further hypothesised that students who subscribed to the moving crowd model should perform well when the resistors were doubled. This is because the serial set up should remind them of how a sequence of turnstiles serves to slow crowds down. The parallel set up should remind them of how a choice of turnstiles serves to speed them up. Gentner and Gentner’s results provide strong support for both hypotheses.

Figure 1.2 Some simple electrical circuits

Related to Gentner and Gentner’s research is a study reported by Shipstone (1985). In this study, a paper-and-pencil test was administered to pupils aged 11 to 18 at three British comprehensive schools and to A-level students at a sixth form college. All participants had embarked on the study of electricity. One item in the test used a circuit like (c) in Figure 1.2, indicating clearly the direction in which the current was flowing and interpreting the doubled symbols as resistors. Using a multiple choice format, pupils were asked to predict the consequences of increasing and decreasing the resistance before and after the indicator. (If the current was flowing clock-wise in (c), Y’ would be before the indicator and Y” would be after.) The pupils were also asked to justify their responses in writing. In reality the location of the resistors makes no difference; it is their strength that counts. However, a very large number of pupils failed to appreciate this, believing that only resistors before the indicator had any significance. As one pupil put it ‘R1 [as it was labelled in Shipstone’s study] is after the lamp … hence it will not hinder the voltage’ (Shipstone, 1985: 41). Interestingly, the frequency of this belief increased from 30 per cent of the pupils at age 11 to 12 to 80 per cent at age 13 to 14. Moreover, although its frequency then fell away again, it was still proposed by 30 per cent of the sixth form sample.

Explanatory problem solving

The studies just described provide strong evidence for the existence of preformed ideas. Nevertheless, they are limited to one form of physics problem solving, namely prediction. Thus, based on these studies alone, it would be difficult to claim that interference from pre...