eBook - ePub

Small Farm Development

Understanding And Improving Farming Systems In The Humid Tropics

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Small Farm Development

Understanding And Improving Farming Systems In The Humid Tropics

About this book

This book analyses several aspects of small farm production systems that increase efficiency when the farmer's production resources are limited. It is concerned with the goals of the individual farmer and his immediate family.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Small Farm Development by Richard R Harwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Small Farm Development

1

A New Approach to Analysis

The factors that limit food production on the world’s small farms are virtually unlimited in number and variety. The small farmer does not have enough land to produce more; or family labor is scarce; or his family feels a competing need for cash income from nonfarming pursuits: the possibilities are endless. Land is the first limiting factor in most areas: more than 90 percent of all tropical farms are less than 5 hectares in size. National averages in Asia are often less than 3 hectares, as in the Philippines; or between 1 and 2 hectares, as in Bangladesh. Low soil fertility and poor soil structure, poor seed, water shortages, extreme temperatures, lack of access to inputs and markets—all limit the capacity of the small farmer in the tropics and subtropics to produce food.

A contrast in development approaches

Faced with these multiple limitations, each a formidable problem, agricultural development programs inevitably tend to concentrate their efforts on those few factors that seem most crucial to crop production and easiest to improve. The resulting advances—the development of high-yielding varieties of key grain crops, the proliferation of irrigation systems, and the widespread introduction of fertilizer and other inputs—have helped greatly to keep national food production in the developing countries more or less in step with rapidly rising demand. So far, however, these production increases have come largely from the most favored farming areas, where

In Nepal farmers use their scarce land intensively. The farmstead areas have carefully tended vegetable gardens and fruit trees. Trees bordering cultivated fields provide compost, animal fodder, and firewood

the constraints on production are relatively light. However, the continuing need for more food production and the growing concern for the well-being of the small farmers who have been largely untouched by the new technologies are drawing attention to the special problems of small farmers in the tropical and subtropical developing countries.

When resources are limited, the key to farm productivity, and thus to the well-being of farm families, is the interaction of varied but complementary farm enterprises. Analyses of these interactions, however, have traditionally focused on larger farms and emphasized labor productivity and return on investment as critical variables. The small farmer in the tropics seldom enjoys the option of varying his capital.

Also, traditional development programs have often been aimed at a single commodity. Not surprisingly, they have been most successful in situations where farmers depend predominantly on a single food grain, and where there is a profitable market for their production. The small farmer often finds such programs irrelevant or unacceptable because they do not encompass the varied mix of crops and livestock that is his daily concern, and because they put him at the mercy of market forces he cannot control and probably does not understand.

This brings us to a distinction between farm development as proposed in this book and its common use in today’s development programs. Farm development is usually considered synonymous with commercialization. The most frequently stated objective of today’s programs is increased farm income. Other indicators of development progress are amounts of cash inputs used and farmer participation in credit programs. The underlying assumption is that greater cash flow across the farm boundaries (increased commercialization) is a true indicator of increased farm productivity and improved farm family well-being.

Our slowness or outright inability to commercialize large segments of the world’s farmers and the questionable effects of such commmercialization on family well-being in other cases lead us to a more general concept of development for small farms. Farm development as used here signifies a progression to more efficient and more productive use of limited farm resources. It nearly always implies an increase in labor productivity and an increase in quality or quantity of the food and fiber output of a farm unit. In the early growth stage, in particular, it probably will not involve commercialization.

In contrast to traditional approaches, the analysis and attack proposed in this book are based on the agricultural systems actually used by small farmers in tropical areas. The farming system is a set of biological processes and management activities organized with the available resources to produce plant and animal products. The farmer’s resources include such physical factors as soil, sunlight, and water, plus such economic and social factors as cash and credit, labor, power, and markets. The limits of the analysis in this book are strict: the farmer himself and the resources he has to work with on his small land area. Accordingly, the analysis includes marketing activities only to the point where the product reaches the first off-farm handler. Processing activities are included only when the crop requires preparation for first-stage marketing, as in the case of tobacco, which must be dried, or grain, which must be threshed.

An effective small farm development method

The analytic process described in the following chapters is evolving constantly; it must be adapted to each agricultural environment and farming system to which it is applied. It is not an ideal, mathematical system of precise measurement and by-the-book interpretation. Such an academic system would necessarily be irrelevant to the small farmer’s situation.

The analysis of farming systems properly begins with the identification of significant interactions: of people with plants, plants with animals, plants with other plants, and so on. Each interaction propagates others; the problem for the analyst is to sort out the various reaction products, define the significant ones, and match them with the farmer’s goals. To do this, the analyst must order the variety and complexity that are characteristic of tropical farming systems. The aim of the process is to identify situations in which existing farm resources are inefficiently used. The process succeeds when it defines changes in the farming system that result in increased productivity.

To understand the farmer’s agricultural system, the analyst must classify the various environmental factors to which the farmer responds and identify local farms where these factors are expressed in varying degrees. The basic factors to be analyzed are soil and climate. Local crop and animal production data are also important. These factors must be viewed in terms of the farmer’s own goals and priorities, which figure as importantly as objective physical and biological considerations in his decisions about how to farm. His need for food, his competing need for cash income, his status in the community, his desire for stability and security, his motivation to conserve energy and other resources—such subjectively perceived values are also factored into the farmer’s agricultural equations.

Only after he has gathered this information and understood its meaning for the farmer can the analyst plan appropriate changes in the farming system. The planning process involves the scientist with the farmer in deciding what modifications and innovations to try. Each brings to the planning process his own perspective and his own wisdom. The farmer contributes his intimate, often tacit, understanding of his own situation and the factors that influence his productivity. The scientist has the objective information derived from his measurements and observations, plus a familiarity with alternative production technologies from other areas. The scientist and the farmer collaborate on planning and implementing changes, and the results are measured against mutually agreed-upon goals. The careful documentation of their experience with new technologies and systems in well-defined environments makes it possible to extrapolate their results to other, similar situations in any part of the world.

This approach depends to a great extent on teamwork among scientists whose disciplines are highly specialized and insular and who are unaccustomed to working together on common problems. The process proposed in this book requires agronomists to work with crop and soils scientists, animal specialists, agricultural economists, nutritionists, and educators. Interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial to the process, and the team includes a coordinator whose special function is to bring the disparate insights and skills of the various scientific specialists into focus on the problem of increasing the small farmer’s production.

2

The Stages of Small Farm Development

Applied to a farmer or a group of farmers, common adjectives like “small,” “bypassed,” “underdeveloped,” or “disadvantaged” do not convey much useful information. Indeed, they obscure more than they reveal; critical distinctions are lost. Such euphemisms fail to specify the essential differences between the farmers they purport to describe and their more favored cousins; nor do they indicate the diversity and complexity that characterize small farm agriculture.

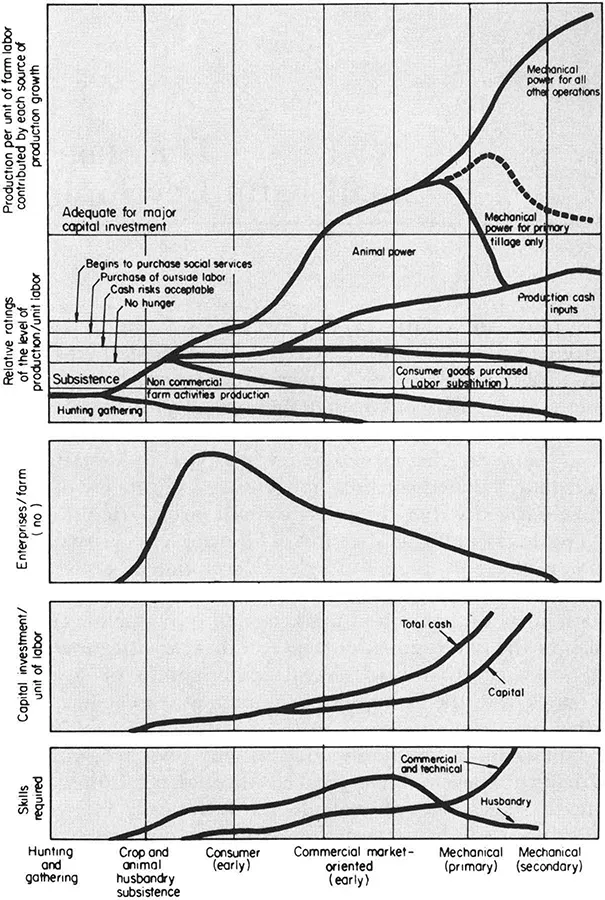

The descriptive classification of farming systems used in this book is based on stages or levels of development, according to the system’s physical environment, local food habits, the availability of inputs and markets, and other factors (Fig. 1). Each of the developmental stages in this classification can be characterized by any of several combinations of crops and livestock, and the examples given are meant to be illustrative rather than exhaustive.

A descriptive taxonomy such as this one recognizes that agricultural development proceeds through a definite series of growth stages, though not always at a steady rate or even continuously. The pattern of development changes according to whether the basic production is cultivated crops, tree crops, or livestock. Cultivated crops provide the bulk of farm products, and they will receive the most detailed treatment in this analysis; but in the tropics a typical farm of B to 5 hectares includes a combination of cultivated crops, animals, and tree crops.

Figure 1. Labor productivity, number of farm enterprises, cash investment, and skills required in different agricultural growth stages when markets for high-value crops are limited. (Source: IRRI)

Stage I: Primitive hunting-gathering

Until the recent discovery of the Tasaday tribe of Mindanao in the Philippines, hunting-gathering as the sole means of subsistence was believed to be extinct. Partial hunting-gathering systems are still found in many societies, however. Indeed, most farmers who are remote from markets rely on hunting and gathering for some part of their total food production. Throughout Southeast Asia, for example, hill tribes such as the Rhade of Vietnam combine crop and livestock cultivation with the harvest of roots and fruit from the forest. The Rhade diet also includes an occasional wild animal, as well as insects, frogs, crayfish, and small rodents.

Hunting-gathering as an element in a more advanced farming system is also found among Nepalese hill farmers, who gather leaves from nearby forests to compost with animal manure into fertilizer for their intensively farmed land. The labor required by such hunting-gathering activities is varied enough to employ family members of all ages, including children and older people who might otherwise be unoccupied.

Despite its apparent simplicity, hunting-gathering can destroy the natural resource base when population pressure exceeds the ability of the environment to renew itself. In parts of India, for example, all the leaves are stripped from the rapidly declining stock of live trees to provide fodder for the burgeoning population of sheep and goats. When hunting-gathering reaches this stage of resource exhaustion, the productivity of the labor it requires is very low, especially when measured in terms of the cash value or opportunity cost of the time invested in each unit of production.

Stage II: Subsistence-level crop and animal husbandry

Subsistence farming is still common today in remote areas. At this level, more than 90 percent of the farm production is consumed directly on the farm; there is little selling or trading. Such noncommercial farming systems are excluded from any development process or program that involves cash income, marketing of farm products, or purchase of inputs.

Among the subsistence farms of Asia, the number of shifting cultivation farms (which cover roughly 40 percent of Asia’s total crop area) is about equal to the number of fixed or permanent farms. In shifting systems, land area per farm is greater, intensity of land use is lower, and there are fewer crop-animal interactions than in fixed subsistence systems. Fixed subsistence systems, on the other hand, have adapted to higher population pressure on land and have increased resource-use efficiency through more and more “structure” in the farm system.

Subsistence farmers typically produce a great variety of crops and animals. In Asian monsoon areas with more than 1500 mm of annual rainfall, it is not unusual to find as many as 20 or 30 tree crops, 30 or 40 annual crops, and 5 or 6 animal species on a single farm. One group of subsistence farmers on Mindoro Island in the Philippines regularly depends for food on a total of 430 plant species. By the same token, subsistence farming is characterized by diverse labor requirements. Having evolved to produce food year-round, the system provides continuous employment for unskilled labor to tend crops and livestock.

Typically, the subsistence farmer plants some crops—rice, for example—that are preferred by the community but that entail relatively high risks. He hedges against this risk by growing several less valued but also less uncertain crops, such as cassava. In monsoon climates, with pronounced alternations of wet and dry seasons, the subsistence farmer ensures a stable production with long-duration root crops, tree crops, and animals. While it lacks the potential for producing a marketable surplus, and thus supporting a higher standard of living for the farm family, subsistence farming has real strengths. The crop and animal combinations evolved by subsistence farmers can often be adapted to increase productivity on more highly developed farms that are pushing against resource limitations.

Stage III: Early consumer

At the early consumer stage of development, the farmer mar- kets between 10 and 30 percent of his production, and the resulting cash income enables the farm family to avail itself of goods and services beyond the barest necessities. Besides salt and oil for cooking or lamps, the family may buy cloth instead of weaving its own. It may also buy porcelain dishes instead of using homemade pottery. The income from surplus food production may also be reinvested in iron farm implements and other capital improvements. C. R. Wharton has estimated that 60 percent of the world’s farmers market less than half of what they produce.

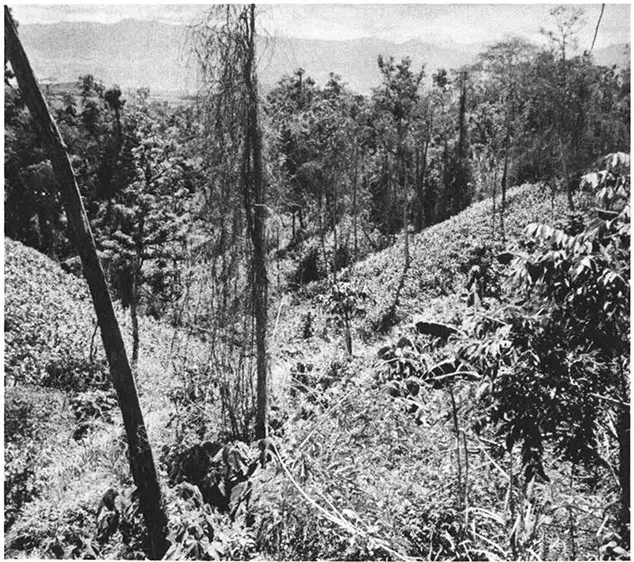

A newly “cleared” slash-and-burn field containing a mixture of taro, cassava, maize, and young fruit trees. The productivity and stability of this system depends on how soon after clearing the farmer succeeds in planting perennial crops.

The consumption of the farm family at this stage is paid for by the productivity of family labor. Productivity is increased by several means: introducing tree crops, such as coconuts or coffee, that yield well with relatively little labor; planting valuable market crops, such as tobacco or vegetables; and using animal power to speed tillage, transport, and harvesting. The change in development stages is exemplified by the shift from upland rice to lowland paddy rice, in which a surplus crop of marketable quality is produced by the intensified use of human and animal power and by improvements in irrigation and tillage.

To become a consumer, even at this low level, a farm family must first rise above the hunger level and be able to accumulate a production surplus that can be turned into cash income. The family gradually increases its crop and animal husbandry skills and usually diversifies into a variety of enterp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Part 1 Small Farm Development

- Part 2 Critical Factors in Small Farm Development

- Appendixes

- Annotated Bibliography

- Index