A recent movement in video games toward the inclusion of adolescent girls as primary subjects is a significant development given the mainstream image, financial viability, and critically-valued status attached to those games. Studies of girlhood have been relatively unexplored within feminist video game analysis, while media critics often devalue “women’s” genres (Bode 2010). Twenty years ago, game narratives formulated around female friendships were mostly confined within the girls’ game genre of the 1990s in games like Chop Suey (Magnet Interactive Studios 1995) and Secret Paths in the Forest (Purple Moon 1997). Such games represented an attempt to attract young girls to computer games, although they unfortunately reinscribed feminine stereotypes while continuing to isolate girls from mainstream gaming. Despite their shortcomings, these games began to experiment with emotional bonds and female connectedness among their adolescent characters, meeting the desires communicated by the market research groups comprised of young girls (Cassell and Jenkins 1998; Ochsner 2015). This chapter examines the complicated affections between female friends and how the re-emergence of this theme (and its improved handling) is interwoven within the ludic and narrative elements of two video games that explore reunions between estranged friends: Life is Strange (Dontnod Entertainment 2015) and Night in the Woods (Infinite Fall 2017).1

Female friendships are traditionally an undervalued form of love in comparison to the social value and academic attention granted to women’s romantic and maternal relationships (see O’Connor 1992; Schaefer 2018). Friendships between adolescent girls have likewise been culturally dismissed and often regarded as a temporary phase in preparation for later heterosexual relationships (as noted by Aapola, Gonick and Harris 2005; Berridge 2016; Hatch 2011; see also Rich 1980). Despite this, Sally Theran’s (2010) study on young girls’ self-esteem found that girls’ adolescent friendships are crucial sites for identity construction and psychological health. As Sinikka Aapola, Marnina Gonick and Anita Harris (2005, 111) write, female friendships are “a powerful cultural force, representing sites of collective meaning-making, and a necessary requirement in the multilayered process of making gendered identities.” Media texts that feature relationships between women therefore meaningfully permit the visibility of a feminine identity that is informed separately from women’s relationships to men (Hollinger 1998).

Troubling these optimistic observations, Alison Winch (2012, 5) proposes that female friendships (at the encouragement of friendship films and lifestyle blogs) rather frequently contain an assemblage of “ugly feelings” that include jealousy, competition, and the policing of normative feminine behavior. Prior to Winch, Pat O’Connor (1992) similarly cautioned against a theorization of friendship between women as unequivocally joyous, productive, and liberating. She cites class difference, oppositional social politics, and limited time and emotional commitment as common barriers. Driven by the views of Winch and O’Connor, I propose that the estranged female friendships in Life is Strange and Night in the Woods attest to the complexities and imperfections of friendships, while simultaneously highlighting their resilience in the face of these conditions. The two games offer a digital space for exploring raw coming-of-age complexities between female friends that crucially remain unobstructed by heterosexual pursuits.2

Set in a bayside town’s high school, Life is Strange is a narrative-adventure game, released episodically in five parts. Its action is primarily driven by its choices and dialogue options that have various effects on the plot’s outcomes. The ability to rewind time to alter decisions and to solve puzzles operates as its defining mechanic. The remaining player actions meanwhile consist of taking photos or interacting with objects and characters in limited explorable areas like the school’s hallways and dormitories. Most of those interactions are optional and non-integral to the storyline’s outcome although they develop greater nuance toward the game’s world-building, particularly in drawing attention to the school’s bullying problem and leaning more about its broader cast of students, teachers, and parents.

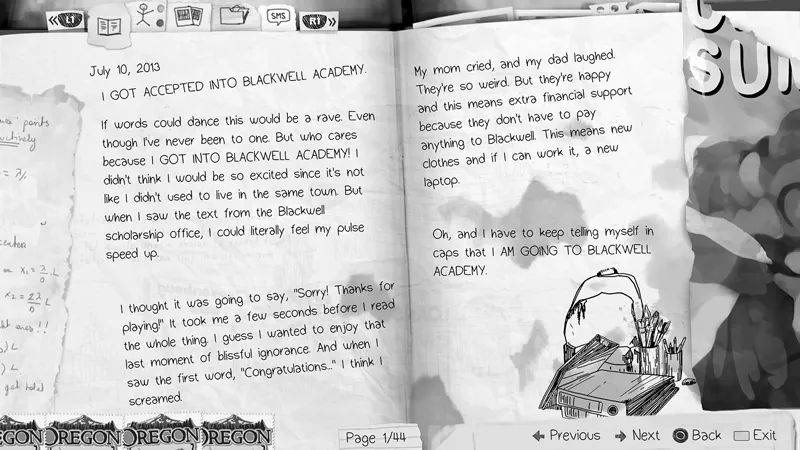

The protagonist is Max Caulfield, a quiet eighteen-year-old student with a passion for photography. She has returned to her former hometown of Arcadia Bay after being accepted for a scholarship at the prestigious Blackwell Academy. Each of the five episode’s key narrative moments and player decisions are summarized from Max’s perspective within the written entries of her diary, accessible at any time within the menu interface (Figure 6.1). The game’s events begin from the discovery of Max’s power to rewind time and progresses as she utilizes those powers to help her friend Chloe Price investigate the truth behind the disappearance of Blackwell student, Rachel Amber. Their investigation mostly involves searching and retrieving evidence and navigating sensitive dialogue puzzles with the rewind feature accessible to amend unsuccessful or disastrous consequences. The rewind feature, however, is limited to its immediate use, that is, once a player progresses to the next sequence in the game they are unable to undo their previous actions. The effects of many decisions are therefore not made apparent until later in the game.

Night in the Woods is a 2D narrative-and-exploration–adventure game. It is set in the economically declining rural town of Possum Springs and features an eccentric cast of anthropomorphic animals. Players will likely spend most of their time wandering the open town, balancing along telephone wires to access rooftops or concealed areas, or initiating casual and humorous dialogue with its various residents. The repetition of exploring the town each day and being rewarded with subtly new experiences—like new characters, areas, or mini-games—effectively captures a sense of living in a small rural community.

The protagonist is Mae Borowski, a college dropout, queer, anti-authoritarian cat.3 Having abruptly withdrawn from college, Mae’s return, intended to be comfortably familiar, is simultaneously disorienting The town’s general appearance and residents are the same, although several businesses have been replaced by large corporate franchises, her friends have unfulfilling full-time jobs and her parents are struggling to keep their house, prompting Mae to gradually learn of the crippling effects of a fading economy subjected upon her hometown’s residents. Night in the Woods’ storyline is not as central as the events that unfold in Life is Strange, where despite Mae’s investigation into what she believes to be a ghost, the game is ultimately characterized by the playful act of mundane wandering. While the mystery of the ghost physically brings her friends together, Mae’s realizations—born from her wandering—meaningfully strengthen their emotional connectedness.

Life is Strange’s Max Caulfield and Night in the Woods’ Mae Borowski are both late-adolescent women who have returned to their small hometowns. Upon returning, they both encounter tense reunions with their estranged childhood friends. The friendship between Max and Chloe collapsed when Max moved to Seattle for five years. She failed to maintain contact with Chloe who subsequently felt abandoned as Max’s departure coincided with Chloe’s father’s untimely death from a motor vehicle accident. Their relationship is a key feature of the game although the nature of the relationship is dictated by the player when presented with the option to kiss Chloe. As Adrienne Shaw (2014) argues, the option itself represents a neo-liberal responsibility for accessing queer content. For the purpose of this chapter the discussion of their relationship will be limited to a reading of their friendship (for notable analyses of Life is Strange’s queer representation, see Knutson 2018; Alexandra 2018).

Mae likewise returns to a tense reunion with her former childhood friend Beatrice “Bea” Santello (hereafter Bea), who is one of two friendship routes the player can pursue throughout the game. Like Chloe, Bea has lost a parent (her mother to cancer) and feels anchored to her hometown due to the redistribution of her college funds toward her late mother’s medical and post-mortem bills. As Mae attempts to restore their childhood friendship, Bea struggles to accept Mae’s decision to drop out of college. The designs of three areas of contention between the two pairs will be elaborated in this chapter: Max and Mae’s unmet expectations upon returning home, their differing levels of maturity when compared to Chloe and Bea, and the conflicting moral compasses of Max and Chloe.

The friendships are inevitably restored in both games regardless of the player’s actions, driven together firstly through their shared detective work. In Life is Strange this is the investigation into Rachel’s disappearance and in Night in the Woods it is Mae’s mysterious ghost. Secondly, the pairs engage in rebellious appropriations of space. These moments represent an empowering use of game space as these young women assert a form of feminist anti-authoritarianism via their occupation in off-limited areas.

These complicated estranged friendships further elicit a feminist potential for they challenge the mythology of an idealized female friendship comprised of unequivocal pleasure and empowerment. They instead attest to heartache, abandonment, and misunderstanding, while eventually renewing their former intimacy after accepting their differences and (re)discovering their similarities. The portrayal of conflict between girls is then not restricted to a harmful promotion of their competition, but potentially serves, as Winch (2012, 71) writes, as “invaluable in offering the female viewer a cathartic space to explore the complexities of women’s relationships.” Regarding other visual media platforms, studies of female friendships continue to expand, yet scholarly attention on this subject in video games has mostly been confined to critical analyses of the girls’ games movement. This is most reasonably due to the limited presence of female friendships within those games. This recent re-emergence of female friendships in video games therefore necessitates updated consideration. Mapping these video game designs deepens how the construction and presentation of female friendships are theorized and in turn encourages designers to continue to pursue productive feminine content in mainstream games.