Conceptual Models of Brazilian Politics

Scholarly interpretations of the Brazilian authoritarian regime of 1964–1985 may be grouped into three major types. Despite their more obvious differences these three perspectives share one implicit assumption concerning the nature of political authoritarianism in contemporary Brazil, namely, that the military regime would be long-lasting. As a matter of fact, comprehensive and very sophisticated analyses of the military regime were published when the dynamics of liberalization described in this essay were already set in motion. We are dealing, therefore, with a process that took the scholarly community somewhat by surprise, and one that was viewed with skepticism and suspicion by some.

The Continuity Paradigm. A first group of students of authoritarian Brazil emphasizes the degree to which the regime drew upon precedent. These scholars believe in the continued relevance of a corporative model that evolved between 1930 and 19451 and consisted of a bureaucratic state sustained by the patronal political authority of the public sector.2 There are vast similarities between this Estado Nôvo of Getúlio Vargas and the post-1964 regime.3 Therefore, according to these scholars contemporary Brazilian politics may best be interpreted as an attempt to adapt a basically authoritarian polity to the minimal exigencies of formal democracy.4 Two implications of this interpretation are that the installation of a military regime in 1964 was a restoration of sorts and that attempts to reconcile authoritarian and democratic forms have produced two structurally similar regimes: “strong” democracies (democraduras) and “benign” authoritarian regimes (dictablandas).5 This interpretation presupposes additional complications since analysts must determine whether the outcomes of particular episodes forecast the prevalence of one tendency—dura or blanda (hard or soft line)—over the other. We find this dilemma in Ronald Schneider’s treatment of the manipulated democracy of Humberto Castelo Branco, the Castelo dictatorship, and Costa e Silva’s failure to humanize the regime.6 This dilemma is also latent in Peter Flynn’s evaluation of the Geisel government, which he believed to be rent by the internal contradictions of authoritarian control.7

Recent cases of transition in Mediterranean Europe and in South America suggest that if a political regime is to change from dictatorship to democracy then, at some point in time, the government constituted under authoritarian auspices will stop acting arbitrarily and cease to engage in systematic and severe deprivations of human rights. In a transition to democracy, restraint ultimately prevails over arbitrariness and recklessness. James Madison believed that “good government” means the absence of tyranny and that tyranny is the systematic and severe deprivation of basic civil liberties. Kalman Silvert developed this further when he defined democracy as “the process of the contained use of reason operating through accountable institutions.”8 Combining Madison’s and Silvert’s definitions we arrive at a relatively universal and culture-free view of “good government,” a designation identified with democracy in Brazil and in other Iberic and Iberoamerican countries in recent years.

Despite the very elegant and pertinent reservations advanced by those suscribing to the continuity paradigm, it is possible to identify and utilize relevant criteria to mark the transition from tyranny to good government in Brazil. I will focus on when and how Brazilian military governments began to use their public powers with more restraint, how this enabled intermediary institutions to reassert themselves, and how the military lost control of the process in ultimately being confronted by two distinct choices: a costly involution and retreat toward authoritarianism or a full-fledged transition to democracy.

The Paradigm of Breakdown. An alternative point of view also acknowledges the momentum of corporatist precedent, but emphasizes the interplay of a series of causal elements that bring about discontinuity. One of the leading proponents of this paradigm, Guillermo O’Donnell, wrote about an “elective affinity” between democratic breakdown and the “deepening” of industrial capitalism in South America.9 O’Donnell’s formulation has been questioned in the case of Brazil.10 But even his critics recognize that the Brazilian regime of 1964–1985 may have been the paradigmatic case of bureaucratic-authoritarianism.11 One finds some elements of the continuity paradigm in the work of Alfred Stepan, but he does not treat corporatism as culture. Instead Stepan views a corporatist installation as a defensive policy response undertaken by the elite.12

Among those subscribing to the paradigm of breakdown, Ronald Schneider is undoubtedly the most explicit and exhaustive, going to considerable lengths to discuss the applicability of different models of modernization and political development to the emergence of the Brazilian military regime.13 One finds a critical utilization of the literature of comparative politics by O’Donnell and Stepan that is far from a simplistic rehash of structural-functional theories gone awry in South America. Their theoretical inspiration is derived from the seminal contributions of Juan Linz, which the scholars in this group reformulated to develop a series of analytical models that describe how democracies deteriorate and fall.14 Although some of these models proffer useful insights, one must apply them very carefully in the case of authoritarian Brazil as it is not clear when the regime broke down.

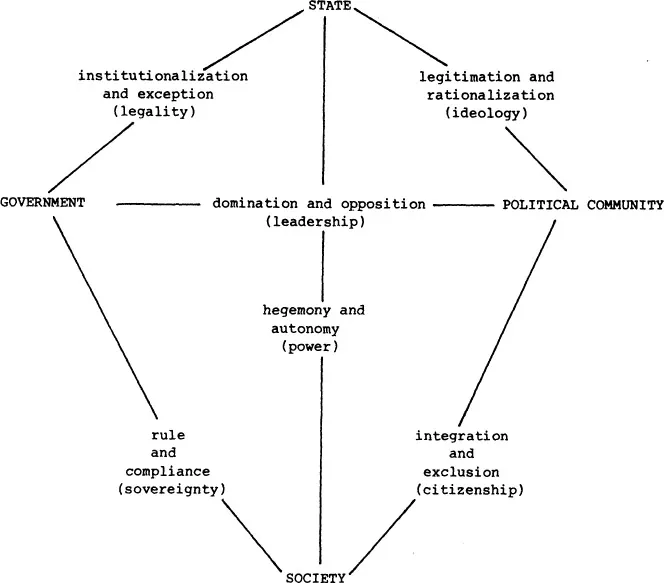

The Paradigm of Rupture. The third approach is quite a contrast to the other two. It brings together a heterogeneous group of authors sharing the belief that the “new style of authoritarianism” resulted from a fundamental rupture with the past. Where others saw crises of government or of regime, these scholars see a crisis of the state itself, which is engendered by late, dependent, and peripheral capitalism. Responding to this crisis, a new class alliance is formed by the more internationalized sectors of the bourgeoisie, the military, and representatives of transnational enterprises. This coalition seeks to promote a new phase of capitalism through the exceptional state.

One conspicuous element within this third perspective is that, despite the very similar causal factors identified by individual scholars, opinion was almost evenly divided between those who considered the new regimes fascist and those who viewed them as something else. Luis Maira suggested that the new authoritarian regimes of South America should not be considered fascist since they lacked key definitional characteristics associated with classical fascism.15 Vania Bambiria and Theotônio dos Santos countered that the question was not how many such characteristics a particular case had but, instead, how many of the essential characteristics were present and operative.16

Totalitarian or Authoritarian? To be sure, key elements of classical fascism were absent from the new authoritarianism in South America. But this debate reflected a deeper concern about the nature of these regimes. At issue was the extent to which the regimes were so close to totalitarianism that they could not be expected to evolve, deteriorate, and decay peacefully. Regardless of this disagreement, scholars in this group believed that since the new authoritarian regimes had been inaugurated through a fundamental rupture of extant patterns of state-society relations they would not break down except through a rupture of the relations they had created.

In the case of Brazil there is a virtual unanimity that the inauguration of the regime came during its most repressive phase, more than four years after the installation of the military government. This delay suggests that either there was considerable disagreement within the military about which project to implement or a complete absence of a project at the time of installation. More important, one must ask what the military sought to consolidate following that inauguration. It is difficult to reconcile the interpretation that it tried to consolidate a fascist regime with the subsequent facts of abertura (political opening). Whereas 1968–1974 has been viewed as an unintended or inevitable “descent into dictatorship,” 1974–1985 has been described as a “liberalization” that became a democratic transition. Therefore decompression (distensão) in its original conception may be viewed as an attempt to return the regime to the configuration of 1964–1968. This would imply that the military recognized that the repressive phase of 1968–1974 could not, in itself, become the regime. In other words, it sought to consolidate a regime that was not a total rupture with the past.