- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Published in 1938, this book contains the autobiographies of Ngidulu, Bugan Nak Manghe and Kumiha, three tribespeople from the Ifuagos province in the Phillippines. A fascinating ethnological and anthropological resource, Barton, a celebrated scholar on the Philippines shares with the reader his long term study of three Ifugao natives. With a final essay on an Ifugao liberal, this book provides an observation on Phillippine pagan tribal life and culture in the early 20th century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philippine Pagans (1938) by R.F Barton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part II

Ngídulu

Ngídulu, of Nunbalabag village (Bitu region), was the best of my informants. His name means "Laziness", and never did a name fit the individual better—and yet, this is true only in a physical sense, for I never ceased to wonder at the activity of his mind, at his intelligence, at his keen insight into motives and men, at his all-embracing knowledge of Ifugao lore generally, and of the remarkably intricate religion, folklore, and adat in particular. Most of all his memory, although it was probably only slightly above the Ifugao average, astounded me over and over. He would be telling about a visit thirty years ago to an agamang. "Who was in that agamang?" I would ask. Then he would enumerate. Rarely would he have to hesitate a moment before recalling the names of at least all the larger girls and boys, and this he could do for any agamang he had ever visited. Not only this, but he knew much of the genealogy and the complicated net of interrelationship of almost all the people in the whole reach of the valley from Ligauwe to Amganad.

However plain I might make it that I wanted him to come on the morrow, he would always have to be called to my bungalow. His village was only about 150 yards away, at a higher level, on a jutting promontory set in the rice fields. He would appear after a while, would mosey along the winding ricefield dykes, climb the stile at the entrance to our village, then the stairway, would enter without greetings or answering to greetings and slump, like a man utterly spent, into a chair or on my cot if no chair were handy. Soon he would be able to draw his feet up to the chair seat and would squat on it as he was accustomed to sit on house-floor or mat during his prolonged recitations of myths or invocations of the deities when officiating as priest.

His enunciation was indistinct and almost inaudible. A helper was doubly, even trebly necessary in working with him and even he, sitting bent forward with ears strained, often could not hear or understand Ngídulu's terse mumblings. But there was always matter in what he said and there were few things in Ifugao culture that Ngídulu did not know, though it was often like rock work to blast explanations out of him. It was not that he was indifferent—it was simply that he had only energy enough to keep his encyclopaedic mind going and none left over for his vocal apparatus. His case was like that of the Mississippi steamboat whose boiler was so small that if the engine worked, the whistle wouldn't blow, and if the whistle blew, it took all the steam and the engine stopped. His lack of energy made him a good listener, and perhaps that is the reason he knew so much.

By Ifugao standards, Ngídulu is, though poor, thoroughly respectable. He has always kept out of, or managed to get out of, trouble and debt. He is decidedly averse to physical work and like many

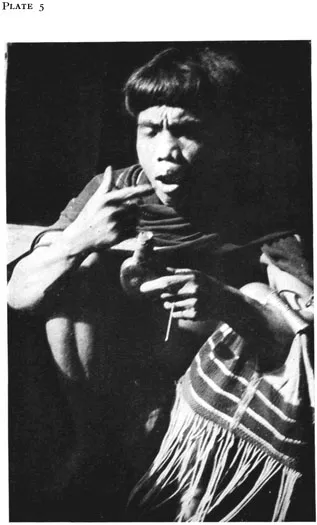

Ngídulu, perched on a chair in my "study", interrupts his narrative in order to convey lime on his moistened forefinger to his betel quid. (Photo by F. Bugbug)

priests evades every sort [note the roof of his house, Plate 6) except one—the spading of rice fields. But he was a very lively boy, rather a ruffian, indeed, and as a youth, a gay blade, though probably not much more of one than the average youth. Whether there may be any connection between the excesses of that period and his present physical laziness, I shall have to leave to someone more competent in physiology. There are intimations in his life story that his lethargy may be inherited.

Ngíidulu had a very keen sense of humour which was always manifesting itself in digs at the ethnographer's expense. For example, in teaching the funeral ceremonies it was necessary for him to assume somebody to be dead and to send the soul away. To have used the soul of a deceased person might have stirred up trouble and to use the soul of a living person might have brought bad magical consequences to that person. I told him to use my soul, which he did. Later, in working with him on the deogeography of the Skyworld, he informed me that a certain region there was the abode of rich men, who spent their time in feasting, drinking, and singing the rich man's epic.

Inasmuch as the Ifugaos assume all Americans to be rich or at least to have rich man's status, I asked him why he had not given my soul the consideration due it, for he had sent it to the downstream region with the souls of the poor.

"I have noticed, Apo," he said, "that when you sit down, the rolls of fat on your belly hang out over your belt. We Ifugaos regard fatness as a calamity, so I sent you to the region of poor folk so that you might become thinner on their camotes that they live on there and become able to climb the mountains without losing your wind as you do."

Questioning, however, brought out that all souls, rich or poor, are sent to the same region (the Downstream Region) in the funeral rites. It could not be explained how souls of rich men got from thence to their abode in the Skyworld. Here was a bit of evidence to add to other similar bits which go to show that two or more religious systems have been imperfectly united to compose the structure of the present Ifugao religion.

On another occasion I was about to photograph a youth who had a lot of nodules in his skin. The lad was posing himself in preparation.

"Never mind getting your face ready," Ngídulu told him. "It's your boulders he wants!"

Frequently Ngídulu would be unable to come to me because he had been called to perform rites for his kindred or co-villagers. He was the most famous priest in the region and in great demand. He would usually try to refuse these calls because he preferred his wage as informant to the chunk of meat he would receive as priest. Sometimes people would come when he was working with me and try to coax him away to perform sacrifices for them. "I am busy with the American," he would say. "And is the American your kinsman that you should teach and teach him and are we the ones who are non-kin?" they would ask with unanswerable logic. It made me feel guilty and I would sometimes let him go, for an Ifugao must not offend his kindred.

From certain events Ngídulu remembers at a definite stage of his growth, I reckon his age at 46 to 48 years. Now let him tell his story. He begins it with an explanation of what is, to the Ifugao, the most important phase of his life: his status with respect to inherited property.

Autobiography of Ngídulu

My great-grandfather was a wealthy man (kadangyan) and gave my grandfather, his third child, a field 1 from the acquired property (ginatang). This field my father inherited.

My mother ought to have inherited three fields, but really received only two. For she was the eldest child and, having the right to choose between the inherited properties of her parents, which she would have, she chose those of her mother, since they were more valuable than her father's. But her mother married a second time and by her second husband bore a son whom she loved more than she loved her other children. This son, she insisted, should have her smallest field, and she urged him to plant it and hold it, if need be, by force. My mother was dominated by her mother and was afraid to resist her half-brother. My father kept out of the quarrel and gave her no encouragement to stand up for her rights.

Not only this, but my father sold his own field to raise the necessities of life, and finally my mother had to sell hers for the same purpose. [Informant reluctant to go into the details of this calamity. The father is said by our neighbours to have been plain "no 'count".] Consequently, though the eldest child, I inherited no fields, but have been able to buy one from my earnings as priest and from the proceeds of chicken-raising. Since I had no older brothers and sisters to carry me in the blanket-sling (oban) this was done by Ayuhip, a little girl, my "mother" on the father's side.1

My earliest memories are of accompanying my parents to the fields when they went to catch fish and of playing and bathing in the fields on these trips. One day I followed my mother far to her hill-farm in Atugu—that place which [according to tradition] Kingi, the first settler in the Bitu region, bought from the Holnad people for a hunting ground. I fell somewhat behind her on the way, and near Atugu a man came round a bend in the trail carrying a load of runo tips for roofing. I had been hearing a lot of talk about kidnapping and was afraid this was a kidnapper, so I began to scream as loudly as I could. My mother rushed back in great alarm, for kidnapping was of almost weekly occurrence at that time in our own or a neighbouring region. I cried out that the man was trying to kidnap me.

"Why it's not a boy but runo tips that I have in my arms, and besides, you are my 'son'," said the man.

Ngídulu's house, the roof of which testifies to his aversion to toil; granary in the background

My mother began to laugh and Anaban (that was the man's name) and she chewed betels together (for he was a "brother" of my father1). They ridiculed me for my mistake and Anaban told me I must learn who my kindred were. Yes, Apo, I suppose that this incident must have made quite an impression on my child's mind, that it gave me my first idea of the kinship group (himpangamud).

Only a short while before this, my father and six of our kin from our own village and Ginauwa village, near by, had gone on a slave-catching expedition which was led by our kinsman Bantian. They had intended to go to Ubwag region, the other side of Mampolya. But passing through the farther part of Mampolya, they captured a woman who was working on her hill farm. On the way back through Mampolya, the woman screamed for help and many men rushed out against them [armed with spears and shield]. But they fought stubbornly and succeeded in bringing the woman back to our village of Nunbalábag. For six days the woman's kin stayed in the forests round about our villages, watching for a chance to rescue the woman or retaliate on some of us, but none of our folk were hurt except one man, who was slightly wounded in the foot. Our neighbours helped in the defence. When the enemy left on the sixth day, Bantian shouted after them,:

"You people of Mampolya! Do not try to retaliate on us kindred of these towns, for we stick together like one man. Retaliate on the in-laws of our relatives by marriage."

This was a very strange thing to say, and I have never been able to understand how he came to say it. [Bystanders are also puzzled.] It would seem that such an invitation would turn all the groups allied to ours by marriage against us. [Discussion by bystanders arrives at this conclusion: "Retaliation was certain. Of course, a man would like to see that retaliation visited on his kin by marriage rather than on his blood kin, but it was unwise to voice the wish. It was certainly a strange thing for an Ifugao to say." But later in the afternoon, in comes an old man from Mampolya. Ngídulu reminds him of the incident and he tells us that the captured woman was a relative of some of the relatives by marriage of the kidnapper's group, so that the point of Bantian's words was: "Retaliate on yourselves!" Ifugaos were far less careful to avoid kidnapping a relative of a relative by marriage than they were to avoid taking the head of such a one.]

Paduwauwon, kinsman of the captured woman, went to Maluyu village in the Anao region to retaliate and carried off a small boy, Ganu, one of our kindred, in a basket. The way he did this was as follows: he saw the boy playing alone in the outskirts of the village, spoke to him kindly, and told him there were kidnappers all around.

"You'd better get into this basket I have and let me carry you safely past them," he said.

The little fellow, about my age and in terror, no doubt, just as I was from hearing continual talk about kidnappers, did as Paduwauwon suggested and never cried out once as Paduwauwon carried him over the ridge to Mampolya.

On the third day our people learned what had happened to the boy and some of our kindred together with some of the boy's kindred from Anao and Hingyón went over the mountain to Mampolya to rescue him. Tayaban of our village was wounded in the first skirmishing, however, and our people, believing they had mistaken their omens,1 returned without the boy.

The woman that our kin captured was sold in the lowlands for six carabaos (water buffaloes), which were distributed as follows: one carabao to the monkavivil [the agent who took the woman to the lowlands and sold her]; one carabao to the kindred and neighbours of Dayakut village who helped us during the attack (dotal); four carabaos were distributed among the captors and used for the payment of debts and the purchase of rice fields...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- PREFACE

- I. INTRODUCTION

- II. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF NGÍDULU

- III. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF BUGAN NAK MANGHE

- IV. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF KUMÍHA

- V. AN IFUGAO LIBERAL?

- INDEX