![]()

Chapter 1

The Need for Curriculum Development

The term curriculum development is a fairly new one in the educational language of this country although it is now being used with increasing frequency. The activity implied by the term is one which a small number of thoughtful and gifted teachers have always carried out, an activity which is now slowly becoming accepted as part of the professional responsibility of all teachers.

The purpose of this book is to explain what is meant by curriculum development and what is involved in curriculum planning. It outlines the relationship among the various elements in the curriculum and explains the factors which influence it.

Its purpose is not to suggest to teachers either what or how they should be teaching their pupils. It will not discuss, for instance, the desirability of teaching a foreign language to all pupils in secondary schools or of introducing vertical grouping or the integrated day into primary schools. Decisions such as these are best made by the teachers in the schools on the basis of a complete set of evidence which only they are in a position to collect. It is hoped, however, that what this book will do is to help teachers to establish a logical process which will enable them to build a curriculum which at any given time is the best one they can provide for their pupils. It will also indicate the factors which influence the curriculum and which, therefore, need to be taken into account in curriculum planning.

WHAT IS CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT?

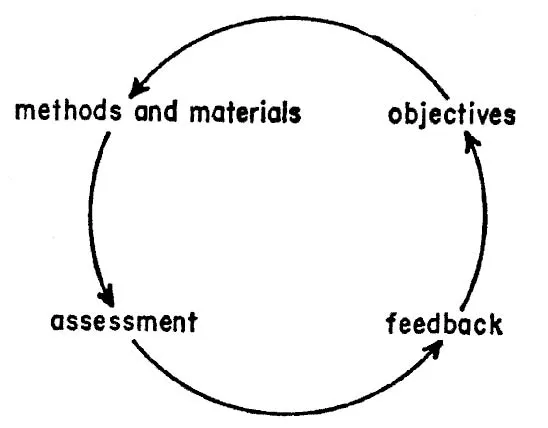

Teachers need to establish very clearly what they are trying to achieve with their pupils, then to decide how they hope to do this and finally to consider to what extent they have been successful in their attempts. In other words, the planning of learning opportunities intended to bring about certain changes in pupils and the assessment of the extent to which these changes have taken place is what is meant by curriculum development. The Schools Council’s Working Paper No. 10 sees this as involving four stages:

(a) The careful examination, drawing on all available sources of knowledge and informed judgement, of the objectives of teaching, whether in particular subject courses or over the curriculum as a whole.

(b) The development, and trial use in schools, of those methods and materials which are judged most likely to achieve the objectives which teachers agree upon.

(c) The assessment of the extent to which the development work has in fact achieved its objectives. This part of the process may also be expected to provoke new thought about the objectives themselves.

(d) The final element is therefore feedback of all the experience gained, to provide a starting-point for further study.1

This last point suggests that curriculum development is a cyclical process and it is indeed helpful to think of it in this way.

Figure 1. Curriculum process

Such a concept of curriculum development implies that there is no one starting-point and that it is a never-ending process. For purposes of discussion there has to be a starting-point and a particular sequence of the stages in the process has to be suggested, but in the practical situation this is not necessarily so. This point will be developed fully in a later chapter.

THE NEED FOR PLANNING

Nowadays there is a greater interest in education on the part of the general public and employers. Schools and teachers are frequently criticised for the education they are providing and teachers are being encouraged, or even pressurised to make changes. Most people would accept that there must be innovation of some kind. We live in a changing society in which new knowledge is constantly being discovered and in which old knowledge is being proved wrong. It is no longer possible for even highly educated specialists in some fields to know everything in their own specialism. This problem of the tremendous increase in knowledge means that there has to be an even greater selection of what is to be learned as well as a reconsideration of how learning should take place. With the realisation that pupils must be prepared to cope with the demands of a society which is changing so quickly, teachers need to reappraise what they are offering to their pupils. The fact that a wider range of objectives is being sought in schools emphasises the need for careful planning.

Naturally enough in a changing society, the schools, which are a part of that society, are changing too. The last few years have seen changes of many kinds. There have been changes in the structure of schools, like the development of comprehensive education and the introduction of middle schools. There have been considerable changes in attitudes to discipline and relationships between teachers and pupils. There has been a blurring of subject boundaries, the introduction of a greater variety of teaching methods, the use of a wide range of audio-visual aids and the development of new techniques of examining. These are some of the more prominent changes in recent years. It might be argued, in the light of a vast amount of evidence of change which could easily be amassed, that teachers are doing enough, and that they are in fact responding sufficiently to the demands of a changing society.

THE ELEMENTS OF THE CURRICULUM

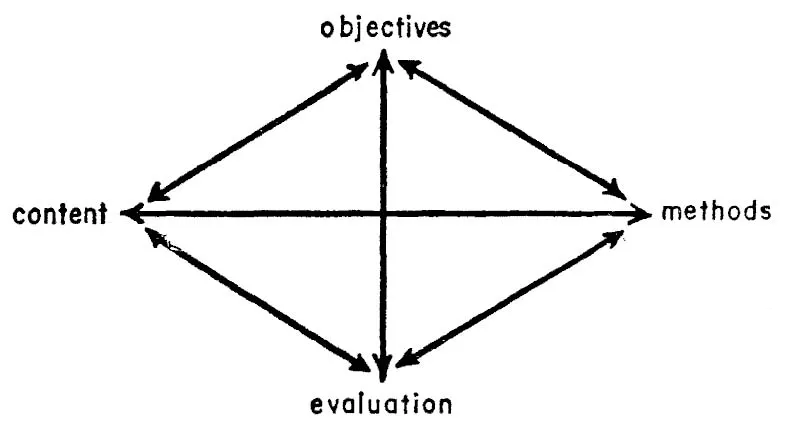

Two answers can be given to this argument. The first is that teachers tend to be practical people, very much concerned with getting on with the job of teaching the pupils in the classroom. This attitude has led them to be concerned very largely with only two aspects of curriculum development, namely those connected with content and method. Consequently, changes that have taken place have tended to be concerned with content and method although objectives are implicit in these changes. Important as these two aspects of learning and teaching are, they should not be treated in isolation from the other two aspects of the curriculum, objectives and evaluation. As we shall see later, the four aspects are closely interrelated and changes to any one aspect may affect all the others. This close relationship is illustrated in the following diagram:

Figure 2. Elements of the curriculum

The elements in Figure 2 can be compared with the diagrammatic representation of the curriculum process in Figure 1. There is a difference only in terminology: content is used instead of materials, and assessment and feedback have been put together as evaluation. Each element of the curriculum is given thorough study and attention during the process of curriculum development.

A LOGICAL PROCESS

The second answer to the argument that teachers are responding to the demands and need for change is related to the first, and the point has been made previously. It is that change should be planned and introduced on a rational and valid basis according to a logical process, and this has not been the case in the vast majority of the changes that have already taken place.

The reason for this deficiency is quite clear: the knowledge and skills necessary to undertake curriculum development in such a way have not in the past been part of a teacher’s initial training. (This situation is currently being remedied in some areas of the country.) It is well known that teachers in this country have always cherished their freedom to decide what they should teach and how they should teach it, a privilege which colleagues in other countries do not always have and which they may regard with a certain envy. However, this privilege brings with it certain responsibilities, including that of providing for pupils an education which is relevant to the society in which they live now and to the kind of society in which they are likely to live as adults. This means that teachers must acquire sufficient knowledge, skill and experience to make the kind of decisions which will enable them to do this. Such expertise and experience is not acquired overnight and there is some evidence1that continuing teacher education of this kind might best be achieved through actual participation in curriculum development activities, a setting in which theories are put to the test in a practical situation. This evidence points the way to an alternative form of in-service education for teachers, a form which would have a real influence on classroom practice.

THE PRESENT POSITION

Some teachers have always been interested in and willing to carry out curriculum change, and this is certainly true of present-day teachers. One has only to visit schools of all kinds or even to read educational journals to find evidence of the vast amount of innovation and experimental work which teachers are undertaking at the present time. The question arises, however, whether the innovations and the experimental work are being carried out for sound educational reasons or whether they are the result of some teacher’s whim or fancy, or of someone jumping on to an educational bandwagon, or of an educational ‘keeping up with the Jones’s’, or of the work of one or two highly gifted teachers developing an idea which worked for them and their pupils in their particular situation, but which might not be relevant or suitable for other teachers and pupils in other situations. Reasons such as these are not sufficiently soundly based for making curriculum change and must be replaced by reasons with a more logical and valid basis.

Other teachers might be described as traditionalists; they accept and follow the pattern that has been long established in the school without considering whether it is what ought to be offered to present-day pupils. Other traditionalist teachers offer what they themselves learned at school, in the belief that since it was all right for them it must be all right for their pupils, disregarding the fact that society today is not like the society in which they grew up.

In some cases curriculum content is determined by the interests and abilities of the teachers. Teachers in this country are in a position to inflict their own pet hobbies and interests on their pupils, should they choose to. The deep interests and outstanding abilities of teachers can frequently be used to great advantage in schools, a point which will be developed more fully later, but these sometimes cause an imbalance. Another form of imbalance which occurs in many schools comes about when new subjects are introduced into the time-table or when new sections are introduced into a syllabus. Because there is no properly established and logical basis on which to make decisions about what should be included and what could be omitted and because these decisions are sometimes emotionally based, the time-table and syllabuses become overcrowded and unbalanced.

The need to regard curriculum development as a dynamic and continuing process, which at the same time can serve as a vehicle for continuing teacher education, cannot be stated too strongly. Participation in co-operative curriculum development activities can lead to a greatly increased professionalism in teachers. On the other hand, there may be some danger that with the vast output of schemes from the national curriculum development projects, teachers using these without undertaking any curriculum development work of their own might come to be regarded as technicians rather than professionals.

SETTINGS FOR CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

The activity of curriculum development can be carried out in a variety of settings, either by an individual teacher or by groups of teachers working together. An individual teacher can undertake curriculum development for his own class in a primary school or for a subject for one or more classes in a secondary school. Obvious advantages derive, however, from either the whole staff in fairly small schools or groups of teachers in larger schools working together. There is the benefit of their joint knowledge and experience, the benefit of their complementary skills and expertise, the benefit of the ideas that are developed through interaction with each other as well as the benefit of a wider application of the results of their work than would be the case with an individual teacher. Perhaps the greatest advantage that a whole staff or a group of teachers working in their own school have is not only that they can undertake their development work with a detailed knowledge of all the relevant factors about their pupils, themselves, the school and their whole situation but also that there will be a consistency in the curriculum they plan. This point will be discussed more fully later. It will be obvious, however, that within any one school a combination of these approaches could be in operation.

In recent years large numbers of teachers’ centres have been established and these provide another setting for curriculum development activities. Work in a teachers’ centre has some of the advantages mentioned for groups of teachers working together in their own schools, together with the possibility of expert guidance in the process of curriculum development from the centre leader and the possible provision of resource materials, equipment and facilities which might not be available in all schools. Work in teachers’ centres has the advantage of wider interaction than is possible in any one school and the centre provides a setting of a non-hierarchical nature where teachers may discuss new ideas in a situation free from anxiety.

Curriculum development is also carried out at the national level under the auspices of the Schools Council and the Nuffield Foundation. The usual pattern here is for a small team of teachers and lecturers to be appointed to undertake the work on a full-time basis. Materials which they prepare are sent to a small number of schools where they are tried out and commented upon and returned. This procedure may go on several times before the materials are considered suitable for publication. At this stage induction courses are held so that teachers can learn how to use the materials and also how to induct other teachers in their own areas. The materials might be one of two kinds. They could be in the form of programmes, like the Nuffield language courses, where there is a teachers’ guide suggesting the methods to be used, and also pupils’ materials. Alternatively, they might be more in the nature of resource materials, in which case the teacher would need to incorporate them into a course which he himself would develop.

Large numbers of national projects will be publishing the res...