- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biosensor Principles and Applications

About this book

Considers a new generation of sensors for use in industrial processes, which measure the chemical environment directly by means of a biological agent mainly enzymes so far. Various specialists from Europe, the US, and Japan identify the device's place in their disciplines; review the principles of m

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Biotechnology in Medicine1

What Is a Biosensor?

Pierre R. Coulet

CNRS-Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1

Villeurbanne, France

Villeurbanne, France

DEFINITION AND BACKGROUND

The abundant literature that can be related to the keyword Biosensor proves without doubt that the field is attractive. It is an interdisciplinary area for which sharp limits cannot be defined easily. The concept of biosensor has evolved; for some authors it is a self-contained analytical device that responds selectively and reversibly to the concentration or activity of chemical species in biological samples. No mention is made here of a biologically active material involved in the device; thus any sensor physically or chemically operated in biological samples can be considered a biosensor. This definition is obviously too broad but may involve, for instance, microelectrodes implanted in animal tissues, like brain. For most of the authors in this book the association of a biological sensing material with a transducer is compulsory, and even if different definitions are given, a biosensor can be simply defined, in a first approach as a device that intimately associates a biological sensing element and a transducer.

The first biosensor described, even if the term was not used at the time, was the combination of the Clark amperometric oxygen electrode serving as transducer and the enzyme glucose oxidase as sensing element for glucose monitoring. In 1962 Clark and Lyons (1) took advantage of the fact that an analyte like glucose could be enzymatically oxidized with, in parallel, consumption of the coreactant O2 or the appearance of a product, H2O2, which could be electrochemically monitored. The enzyme, retained by a perm-selective membrane, thus added to the amperometric detector a high selectivity that could not be obtained without the bioelement.

During the following decade a lot of effort was devoted to obtaining bioconjugates for enzyme immunoassays. Various methods for enzyme immobilization were also described, including adsorption, entrapment in a gel lattice, covalent binding trough activated groups on the support, or the use of a cross-linking reagent (2).

In 1967 Updike and Hicks (3) gave the name enzyme electrode to a device comprising a polyacrylamide gel with entrapped glucose oxidase coating an oxygen electrode for the determination of glucose. Besides amperometry, potentiometric electrodes were also proposed by Guilbault and Montalvo in 1969 (4).

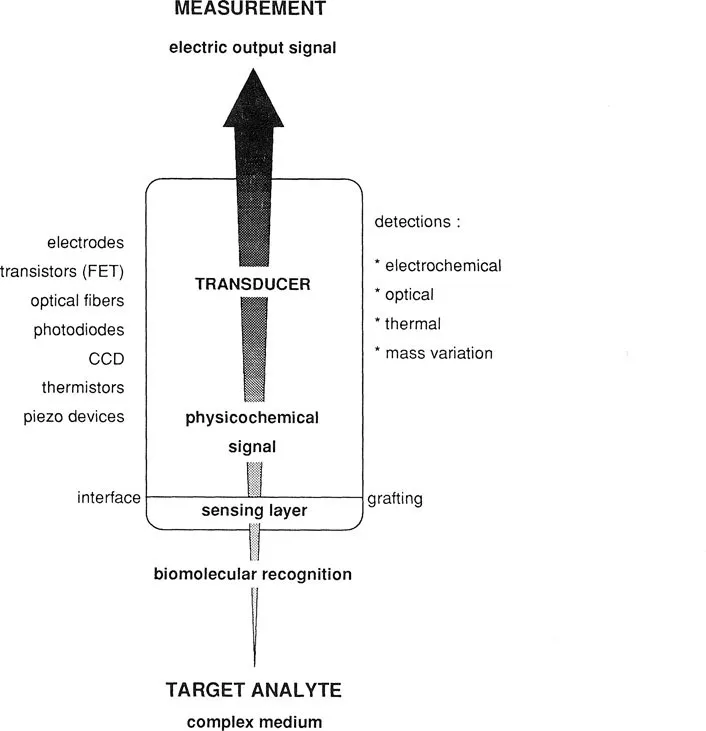

Since the early 1970s various combinations of biological material associated with different types of transducers gave birth to the larger concept of “biosensor.” As a matter of fact, as exemplified in Figure 1, a biosensor associates a bioactive sensing layer with any suitable transducer giving a usable output signal. Biomolecular sensing can be defined as the possibility of detecting analytes of biological interest, like metabolites, but also including drugs and toxins, using an affinity receptor (enzymes being the simplest and historically the first employed), which can be a natural system or an artificial one mimicking a natural one, able to recognize a target molecule in a complex medium among thousands of others.

To obtain a usable output signal that can be correlated with the amount or concentration of analyte present in the medium, multiple events must take place sequentially. Briefly, a first chemical or physical signal consecutive to molecular recognition by the bioactive layer is converted by the transducer into a second signal, generally electrical, with a transduction mode that can be electrochemical, thermal, optical, or based on mass variation. The selective molecular recognition of the target molecule can theoretically be achieved with various kinds of affinity systems, for example (but not exclusively),

Enzyme for substrate

Antibody for antigen

Lectin for sugar

Nucleic acid for complementary sequence

The first problem we must face is the degree of bioamplification obtained when molecular recognition occurs. If the bioactive molecule present in the sensing layer is a biocatalyst a reaction takes place in the presence of the specific target analyte, and a variable amount of coreactant or product may be either consumed or produced, respectively, in a short time depending on the turnover. Biocatalysis thus corresponds to an amplification step generating a chemical signal.

In contrast, the use of antibodies for the detection of antigens is not normally a biocatalysis phenomenon, and different approaches can be considered. A bioconjugate involving a bound enzyme can be prepared, and the presence of the target antigen is determined through the related enzyme reaction. Conventional detection has already been described with enzyme electrodes. New approaches are now being intensively explored, and antibody-antigen binding can be sensed directly through transducers sensitive to mass variation for example.

Another key point to which attention must be paid is the intrinsic specificity of the biological material involved in the recognition process. Some enzymes, for instance, may be strictly specific, like urease, or highly specific, like glucose oxidase. Others, like alcohol oxidase or amino acid oxidases, recognize a large spectrum of alcohols and amino acids, respectively. This intrinsic specificity is difficult to modify, and problems of interferences may arise. For antibodies the specificity can be strongly enhanced by using the monoclonal antibodies now widely produced in many laboratories.

Numerous attempts to find a universal transducer that matches any kind of reaction have been reported. Heat variation, for instance, appears as a signal following practically any chemical or biochemical reaction. Mass variation, consecutive to molecular recognition, also appears very attractive as a universal signal for transduction, especially for antigen-antibody reaction in which no biocatalysis occurs. Piezoelectric devices sensitive to mass, density, or viscosity variations can be used as transducers. The change in oscillation frequency can be correlated to the change in interfacial mass. Quartz-based piezoelectric oscillators and surface acoustic wave-detectors are the two types currently used.

IMPORTANCE OF THE BIOLOGICAL SENSING SYSTEM OPERATING CONDITIONS

Operating Conditions

It must be kept in mind that most of these biological systems have extraordinary potentialities but are also fragile and must be used under strictly defined conditions. For instance, most enzymes have an optimal pH range in which their activity is maximal; this pH zone must be compatible with the characteristics of the transducer. Except for rare enzymes capable of undergoing, for a short period, temperatures higher than 100°C, most biocatalysts must be used in a quite narrow range of temperature (15–40°C).

There is also a demand for measurements in gaseous or solvent phases, however, and until now biosensors work mostly in aqueous media.

Immobilization of the Biological System: Role of the Sensing Layer

The simplest way to retain bioactive molecules on the tip of a transducer is to trap them behind a perm-selective membrane. This has been mainly used in addition to embedding procedures, in polyacrylamide gels for the design of enzyme electrodes. The trend now is to use disposable membranes with bound bioactive material. The availability of preactivated membranes suitable for the immediate preparation of any bioactive membrane thus appeared as a real improvement.

The removal of interference is a prerequisite for the wide use of biosensors in industrial processes. This can be achieved by using multilayer membranes, such as those developed by Yellow Springs Instrument Co. (for glucose or lactate enzyme electrodes), with the enzyme sandwiched between a special cellulose acetate membrane and a polycarbonate nucleopore membrane. The main role of this membrane is to prevent proteins and other macromolecules from passing into the bioactive layer. Cellulose acetate membrane allows only molecules of the size of hydrogen peroxide to cross and contact the platinum anode, thus preventing interference by ascorbic acid or uric acid, for example, at the fixed potential.

For miniaturized biosensors different methods for selectively depositing bioactive layers have been described, and details can be found in corresponding chapters in this book.

WHAT ARE THE CRITERIA FOR BELONGING TO THE BIOSENSOR FAMILY?

A biosensor should respond selectively, continuously, rapidly, specifically, and ideally without added reagent, and then different criteria must also be considered.

What about vicinity? The biosensing element must be either intimately connected to or integrated within a physicochemical transducer. In most cases the systems described fulfill this requirement, but more and more systems are composed of microcolumn on which molecular recognition occurs and of transducer separated from the column for different reasons, mainly the incompatibility of the biosensing reaction (pH for urease in the urea detector) and of the detector itself (pNH3 sensor). Microcolumns can sometimes be replaced by nylon coils, especially in luminescent reactions, with the luminescence enzyme system bound onto the internal wall of the tube, allowing the reaction medium containing the sample to flow through.

Generally a biosensor is described as a small probe or pen-sized device. This is true for a few, but generally the probe must be connected to a signalprocessing system for the readout of results. A question then arises, where does the sensor stop and the instrument begin? Can we consider, for instance, a spectrophotometer operating an enzyme-based fiberoptic probe as a biosensor, or is this simply remote analysis that can be performed outside the standard cuvette?

What is rapidly? For enzyme electrodes a short response time may be between a few seconds and 30 sec, for instance. For immunosensors 15 min is acceptable and considered short compared to alternative techniques that are far more time consuming. For microbial sensors 20–30 min is very short, if we understand that biological oxygen demand (BOD) measurements, for instance, may last 5 days using conventional microbiological methods.

The problem of specificity has already been addressed, but we must keep in mind that interference may occur on the sensing element or on the transducer as well.

It is often claimed that a biosensor must ideally work without added reagent, but what is the exact meaning of a reagentless technique? If we are very dogmatic this means that the biosensor tip can be placed directly in contact with crude samples, undiluted and not pretreated, a drop of whole blood for biomedical analysis or a few milliliters of fermentation broth or raw sewage, for example.

More generally the sample is injected into a reaction medium in contact with the bioactive tip. Do we then consider the buffer used an added reagent, or are only cofactors or coreactants, if required, concerned? Indeed, it is possible to imagine a system with cofactors or coreactants entrapped within the sensing layer with a slow release, allowing the reaction to take place when the target analyte is present. In this case the property of reversibility is still questionable since a system of regeneration in situ must be conceived.

What about reusability? If a disposable sensing tip for a one-shot determination is considered, what is the difference, in terms of cost and efficiency, when taking into account the preparation of the bioactive part, from a device in which reagents must be added for each measurement?

In fact, the design of a biosensor depends mainly on the area in which it operates. To be reliable and of practical use there may be no need for all the qualities of the ideal biosensor. Finally, only one criterion can be retained: convenience.

The following chapters deal with the main types of biosensors based on the concept and principles evoked here. What appears the most difficult but also the most promising is the interdisciplinary aspect of this field and the competency associated with designing these new analytical tools, which are capable of working in real and practical conditions and thus able to challenge well-established methods.

Undoubtedly, the extraordinary capabilities of biomolecules in selective recognition allied to the still advancing evolution of electronics or optics will lead in the near future to unexpected breakthroughs in the analytical field.

REFERENCES

1. Clark, L. C. Jr., and Lyons, C. (1962). Electrode systems for continuous monitoring in cardiovascular surgery, Ann. NY Acad. Sci., 102:29.

2. Silman, I. H., and Katchalski, E. (1966). Water-insoluble derivatives of enzymes, antigens and antibodies, Annu. Rev. Biochem., 35:873.

3. Updike, S. J., and Hicks, G. P. (1967). The enzyme electrode, Nature, 214:986.

4. Guilbault, G. G., and Montalvo, J. (1969). A urea specific ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series Introduction

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- 1. What Is a Biosensor?

- 2. Amperometric Enzyme Electrodes for Substrate and Enzyme Activity Determinations

- 3. Development of Amperometric Biosensors for Enzyme Immunoassay

- 4. Potentiometric Enzyme Electrodes

- 5. Enzyme Thermistor Devices

- 6. Analytical Applications of Piezoelectric Crystal Biosensors

- 7. FET-Based Biosensors

- 8. Chemically Mediated Fiberoptic Biosensors

- 9. Fluorophore- and Chromophore-Based Fiberoptic Biosensors

- 10. Bioluminescence- and Chemiluminescence-Based Fiberoptic Sensors

- 11. Immunosensors

- 12. Microbial Biosensors

- 13. In Vivo Biosensors

- 14. Trends and Prospects

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Biosensor Principles and Applications by Blum, Pierre R. Coulet,Loïc J. Blum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Biotechnology in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.