- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book traces the historical background of the Seychelles from their first settlements through independence from Britain in 1976 and into the early 1980s. It focuses on the issues of environment, social and race relations, economic and strategic forces, and domestic and international politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Seychelles by Marcus Franda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica africana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

History

The Republic of Seychelles is one of the tiniest nations in the world. The total area of all its lands is no more than 171 square miles (444 square kilometers), about one and a half times the size of Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts. According to the 1977 census, the population of the entire country was 61,898, slightly less than Kalamazoo, Michigan, or Troy, New York. Like many other small countries, Seychelles has a romantic appeal, particularly to those who value the intimacy and individualism usually associated with small geographical size, but the islands are being challenged by a number of problems resulting from their past parochialism and their diminutive world stature.

How can a tiny country like Seychelles survive economically? Where can it mobilize the human and other resources to make itself viable in a world of rapid change? How can it preserve its distinctive national identity and cultural values? Is it possible to maintain anything resembling its past peacefulness and unspoilt beauty? What is to prevent it from being overwhelmed by the massive world forces of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries?

These questions are perhaps felt a bit more intensely in Seychelles than in other small territories because the country was historically far more isolated than other lilliputian states and yet now finds itself in the midst of a destabilized ocean area of considerable strategic importance. Completely uninhabited until two hundred years ago, and then only sparsely populated by ex-slaves, European adventurers, and Asian traders, the country was suddenly opened up to major influences from the great powers with the building of a U.S. satellite tracking station in the 1960s and construction of a first-rate international airport in 1971. A massive boom in international tourism has since proceeded apace with conflicts over conservation, fishing rights, and oil exploration. Strategic and commercial factors have stimulated the interests of, among others, the Soviet Union, China, France, India, Tanzania, Kenya, and the United States, as well as a number of Arabs and South Africans. The coup d'etat that took place on 5 June 1977, and the abortive coup attempt of November 1981 are only indications of the turbulence that stirs beneath the calm and breathtaking beauty of this idyllic group of islands.

Physical Features

There are ninety-two named islands in the Republic of Seychelles, plus a number of smaller unnamed bits and pieces.1 These islands are geographically located in four major clusters-commonly called the Seychelles, Amirante, Farquhar, and Aldabra groups-with four small solitary islands (Denis, Bird, Platte, and Coetivy) having been included in the country along with these four main groups because of their proximity. The largest of the islands in terms of land area are Mahé, Praslin, Silhouette, Aldabra, and Cosmoledo, but 97 percent of the population lives on only three islands (Mahé, Praslin, and La Digue). Only these three islands and Silhouette have enough people to have schools. The distance between Mahé, the major island, and Aldabra, the most remote, is more than 700 miles (1,100 kilometers). With 200-mile (320-kilometer) zones of economic rights around each of its islands, the government of Seychelles estimates that it has jurisdiction over some 400,000 square miles (1 million square kilometers) of the Indian Ocean, more than any nation other than France and India (see Figure 1.1).

Unlike other islands in the Indian Ocean, forty-two of the Seychelles islands are geologically distinguished by the fact that they are granitic rather than coralline or volcanic. Recent theories of plate tectonics and continental drift-developed in part by international Indian Ocean expeditions in which scientists from Wood's Hole, Scripps, the Smithsonian and other U.S. institutions participated in the 1960s-have lent credence to the theory that the Seychelles were once, millions of years ago, part of a massive continent known as Gondwanaland, in which India and Africa may have been joined. According to this theory, the Seychelles represent "a continental fragment left during the widening of the Indian Ocean."2

Theories of continental drift have been bolstered by the fact that the granitic islands of the Seychelles are among the few granitic oceanic islands in the entire world, a freak of nature that produces a truly unusual and breathtaking landscape. Massive granite mountains and peaks rise dramatically from long coastal beaches; exposed rock surfaces have been beaten and pounded by the surf into a beautiful assortment of shapes and textures. The highest peak on any of the islands is Morne Seychellois, on the main island of Mahé, which towers 2,990 feet (920 meters) above sea level, but all the granitic islands have surprisingly rugged small mountains or peaks that boom up from the ocean and the sand. Although there are no large rivers in the Seychelles, numerous mountain streams and waterfalls cascade down rocky slopes, fed almost daily by a bountiful rainfall, varying on the average between 50 and 120 inches (130-300 centimeters) per year from the driest to the wettest islands.

As the Seychelles lie only 4° to 11° south of the equator, they are distinctly tropical, but the climate of the islands is moderated considerably by the calm seas that surround them. As the noted botanist Jonathan Sauer has put it, the equatorial, oceanic climate of the Seychelles has an "unearthly mildness."3 All the islands, with one or two minor exceptions, lie outside any cyclone or hurricane belt. They are influenced primarily by trade winds that tend to blow from the southeast during the months of April to October and from the northwest during May to November. Average wind speeds are only 10 to 18 knots per hour, depending on the time of year, which means that a damaging storm is an exceedingly rare event (the only known hurricane to strike any of the inhabited islands occurred in 1863). The northwest winds bring rains that are known as the monsoons, but they are also so tame as to seldom cause any damage. Actual rainfall is rather evenly spread throughout the year (it usually rains a bit every second or third day, with rare exceptions) so that relative humidity is always quite high (75 percent or more all year round). Temperatures seldom fall below 70°F (21°C) and never rise above 90°F (32°C) even on the hottest day of the year. Light and constant cool breezes from the sea tend to make the climate idyllic throughout the year and at any time of day.

The coralline islands are quite different from the granitic islands in several important respects. They were originally formed by the activities of a small sea animal called the coral polyp, which usually anchored itself onto some of the rocks or mountain peaks below the ocean's surface and then sucked in seawater as a means of extracting the nutrients with which it built coral reefs. All the Seychelles islands have many coral reefs off their coastlines, but fifty of the largest coral accumulations have themselves become named islands. The coralline islands are remarkably flat, rising barely a few feet above sea level, and none of them are nearly so lush and teeming with vegetation as the granitic group. Few of the coralline islands have any permanent population because they lack drinkable water; those that do have settlers have only a handful. The largest coral island is Aldabra-one of the largest atolls in the world-which is essentially a massive lagoon encircled by coral land barriers. Aldabra itself is 22 miles (35 kilometers) long and 8 miles (13 kilometers) wide; its lagoon is almost large enough to contain every one of the islands of the Seychelles if placed side by side.

Figure 1.1. Seychelles Exclusive Economic Maritime Zone. Map drawn by Ministry of Works and Port, Survey Division, government of Seychelles, Victoria, Mahé, and published in the 5 June 1978 issue of The Nation, Seychelles' only daily newspaper. Published by permission.

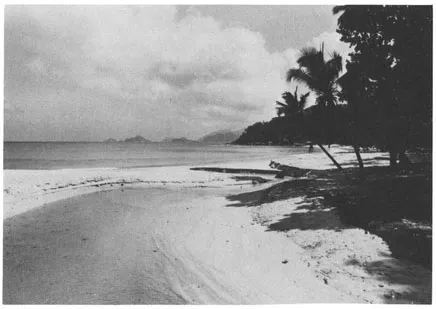

Figure 1.2. A view of one of the thousands of wide and unspoiled beaches on the islands. Author's photo.

Early Exploration

It is primarily the distance of the Seychelles fragments from other land masses-Mahé, the main island, is 980 miles (1,568 kilometers) from Mauritius, 1,748 miles (2,800 kilometers) southwest of Bombay, 990 miles (1,584 kilometers) east of Mombasa, and 1,410 miles (2,256 kilometers) south of Aden —that produced the extremely isolated conditions in which the islands existed until recently. Isolation was also encouraged because the routes of pre-European seafarers on the Indian Ocean-Arabs, Persians, Indians, and Chinese-followed a monsoon arc that brought them up the coast of Africa and then across to India, far to the west and north of the Seychelles.4 There are old Arabic manuscripts (dated 810 and 916 A.D.) describing voyages to islands that sound remarkably like the Seychelles, and marks resembling Arab inscriptions have been found on rocks on Frigate and North islands, both in the Seychelles group. A.W.T. Webb, one of the most reliable historians of the Seychelles, speculated that Polynesians "from some place around the Bay of Bengal" may have stopped on the Seychelles in 200-300 B.C. on their way to Madagascar, where they eventually settled.5

Despite these early hints of human contact, however, it is clear that the first permanent human settlement on any of the islands took place in 1771, when fifteen "blancs" (whites) and seven slaves, along with a slave commander named Miguel, five South Indians, and a Negress, came from Mauritius and Réunion, settling first on St. Anne and later on Mahé. Those who immediately followed these first settlers were either Frenchmen who had fled France when revolution threatened, Frenchmen who had quit India earlier when the French had failed there, or, in far greater numbers, African slaves accompanying their masters. In most instances the white men in the new colonies were trying to make or recoup fortunes by establishing a new trade in tortoises and timber. By 1789 it was estimated that more than 13,000 giant Galapagos-type tortoises had already been shipped out from Mahé, and the population of the colony had grown to 591 people (of whom 487 were slaves). In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries a number of British people-primarily from India, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Kenya, and other former British colonies-settled in the Seychelles, either to retire or for commercial purposes, but this influx was surprisingly small considering that the British had ruled the colony for more than a century and a half.

The earliest settlers in the Seychelles did not denude the environment, but they did alter it considerably and rapidly. Before they arrived, hundreds and thousands of years of tropical growth, unmolested by man, had produced a rare ecological wonder, sometimes described as the last truly virgin territory in the world. The first well-documented description of the Seychelles archipelago was by an English expedition known as the Fourth Voyage of the East India Company, which visited Mahé, North Island, and Silhouette in January 1609. An Englishman from that expedition, John Jourdain, then described dense black forests with floors of guano a foot deep and a wealth of sea and bird life. Jourdain's description of the area around what is now the main port of Victoria is as follows:

... there is as good tymber as ever I sawe of length and bignes. and a very firme timber. You shall have many trees of 60 and 70 feete without sprigge except at the topp, very bigge and straight as an arrowe. It is a very good refreshing place for wood, water, cooker nutts, fish and fowle, without any feare or danger, except the allagartes [alligators], for you cannot discerne that ever any people had bene there before us.6

Perhaps the first Europeans to discover the Seychelles were the Portuguese, who explored a number of the islands around Mahé between 1501 and 1530 and named them the Seven Sisters (Sête Irmanas). Both Vasco da Gama and Sebastian Cabot were among the early explorers who visited some of the islands and made charts, and there was a small Dutch settlement that reportedly struggled along on some of the smaller islands from 1598 to 1712. From the time of Jourdain's visit until the first permanent settlements, the Seychelles provided refuge for a number of pirates and privateers.

The most legendary of all Seychelles pirates was Olivier le Vasseur, better known as "La Buze" (the buzzard), who in the 1720s joined with another pirate, John Taylor, and terrorized French and British shipping in the Indian Ocean. Le Vasseur was captured by the French and hanged on 7 July 1730, but just as he mounted the scaffold he is reported to have thrown a piece of paper at the crowd and yelled: "My treasure to he who can understand!"7 The paper contained a map and a cryptogram, copies of which still exist. From 1948 to 1970 a man named Reginald Cruise-Wilkens spent a small fortune in funds collected from speculators, trying (in vain) to find the Buzzard's treasure on the north coast of Mahé, in a honeycomb of man-made tunnels that may or may not have been constructed by Le Vasseur.

The first Americans to become involved in the Seychelles were a group of successful pirates who operated in the Indian Ocean in the late eighteenth century. The most noted of these was Captain Nemesis, a man born on Pimlico Sound in Carolina Colony who went to England and bought himself a commission in the Royal Navy in the mid-eighteenth century.8 In 1762 Nemesis was cashiered on a charge of theft and deported to Australia, but he led a mutiny en route to Australia, took over the ship, and eventually acquired a pirate fleet of fifteen vessels, many of which were based in the Seychelles. A number of historians have reported that Nemesis enjoyed considerable success in part because he was quietly respected and encouraged by the French-because he reserved most of his hatred for the British.

American merchants from Salem and New Bedford, Massachusetts, tried to open up an extensive Indian Ocean trade in the 1780s by selling salted cod to Madagascar in exchange for zebu, the Malagasy cattle. In 1782 Americans constructed an abattoir in Morondava (Mauritius) where zebu were slaughtered, salted, dried, and loaded as beef jerky for eventual sale in the United States and South America. George Davidson reported that 197 ships of U.S. registry were logged in the books at Port Louis (Mauritius) between 1797 and 1810, at a time when Port Louis was a free port. Most of these ships belonged to U.S. privateers buying goods from Mauritian pirates who had in turn robbed them from British ships returning from India. Such practices were helped along by Secretary of Stat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 History

- 2 People

- 3 Politics

- 4 Economy

- 5 Change

- Selected Bibliography

- Index