eBook - ePub

Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry

Asia, Europe, North America and Oceania

Dipendra Sinha

This is a test

- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry

Asia, Europe, North America and Oceania

Dipendra Sinha

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This title was first published in 2001. By giving long over-due detailed consideration to airline deregulation in countries other than the US, Dipendra Sinha makes a unique contribution to the literature on airline deregulation and transport economics.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry by Dipendra Sinha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technik & Maschinenbau & Luftfahrt. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

An Overview of the World Airline Industry

Introduction

Microeconomic reforms not only in the field of airline regulation but also in other fields have been experienced with a much greater pace since the late 1980s and 1990s not just in the developed countries but also in the developing countries. The economies of the former Soviet bloc have also not been immune to the changes. The question about the pace of reforms has long been debated. While some economists prefer quick and drastic changes, others prefer slow and gradual changes. In the field of airline regulation and deregulation, economists have often argued that the United States followed the policy of 'big-bang' by passing the Airline Deregulation Act in 1978. This is contrasted with what happened in Canada and the European Union. These countries are said to have followed a policy of gradualism.

This chapter will discuss a number of general issues, which are important in the context of airline regulation and deregulation. This is the only chapter in the book, which gives some emphasis on international air services. Other chapters will deal more with air services within a country.

World Air Traffic

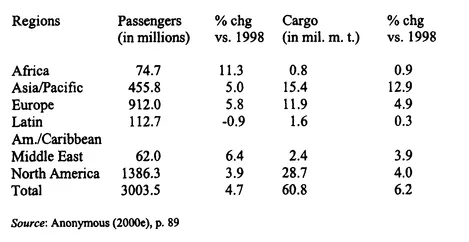

There has been a tremendous growth in air passenger and cargo traffic during the last decade. Table 1.1 gives the number of passengers in millions and cargo in million metric tonnes for various parts of the world for 1999 and the percentage changes from 1998.

It is clear from table 1.1 that North America is the most important region in terms of both the number of passengers and amount of cargo. The region accounted for about 46 percent of the total passengers. Similarly, it accounted for about 47 percent of total cargo. Africa and Asia/Pacific accounted for the highest increases in 1999 in passenger and cargo respectively compared with 1998. However, the total number of air passengers remains low in Africa. The top ten airlines and the top ten airports during 1999 in different categories in descending order were as follows. In terms of revenue passenger kilometres, these were United, American, Delta, Northwest, British Airways, Continental, Lufthansa, US Airways and Singapore. The top ten airports in terms of cargo were all in the United States - Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas/Fort Worth, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Detroit, Las Vegas, Oakland, Miami and Minneapolis/St. Paul. The same for the passengers were Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, London, Dallas/Fort Worth, Tokyo, Frankfurt, Paris, San Francisco and Denver.

Just like any other transportation activities, airline services have all the characteristics of services that have to be distinguished from goods. Air transportation creates both time and place utilities. Place utility is created by moving goods and people from the places where they are to where they need to be moved. Time utility is created when goods and people arrive in time. Delays can lead to additional costs. Also, demand for air transportation is a derived demand in the sense that the demand for these services arises from the demand for goods and the demand for being in certain places.

Even though air transportation is a service, it is much more capital intensive in nature. Aircraft, equipment, maintenance hangers, ground staff etc involve a large sum of money which are normally raised through the issue of stocks or through loans. The on-going replacement of aircraft also adds to the expensive nature of the business. Airline business is labour intensive in nature. Computers may have replaced the need for some workers, but airlines still need pilots, flight attendants, mechanics, baggage handlers, cleaners, managers, cooks, security guards, gate agents and the like.

Generally speaking, passengers account for more revenue than cargo in every country. In this book, we concentrate on air passenger service. Passengers can be divided into two types: business passengers and holiday passengers.

Another feature of the airlines is the seasonal nature of the airline business. The seasonal nature of the airline industry means that airline revenues fluctuate throughout the year. Load factor is a measure of how full an aeroplane is. Holiday seasons are marked by a tremendous increase in the load factor. A break-even load factor is the "the percentage of the seats the airline has in service that it must sell at a given yield, or price level, to cover its costs" (Air Transport Association, 2000). Naturally, rising costs increase the break-even load factor whereas rising fares lower the break-even load factor.

In the US, the break-even load factor is about 65 percent. Most airlines operate close to the break-even load factor. The number of seats in an aeroplane is a crucial determinant of per unit cost. The 'no-frills' airlines such as now defunct Peoples Express in the US used to add as many seats as possible to an aircraft to maximise revenue since it offered very cheap fares. On the other hand, some other established reputed airlines prefer to have a larger business class section with plenty of leg room and larger seats.

Overbooking is a strategy used by many airlines. Overbooking is used because the airlines expect that some ticket holders are unlikely to show up because they have changed their plans. If overbooking is equal to the number of no-shows, there is no problem. However, if overbooking exceeds the number of no-shows, passengers may need to be bumped and compensated. Airlines carefully study the history of the flight segments before deciding on the extent of overbooking.

Deregulation of airfares in many countries means that those airlines are now able to change the airfares quite frequently. The yield or revenue management is the process of finding the right mix of fares for each flight (Air Transport Association, 2000). This is a complicated process. Obviously, the aim is to maximise revenue from each flight. The airline has to carefully assess the demand for the flight before deciding how much discounting it will allow. Too much discounting will fill up all the seats quickly and may deprive an airline of the passengers who book at the last minute and are willing to pay higher prices. On the other hand, too little discounting may lead to a low load factor and thus, lost revenue. In planning such discounts, an airline has to take into account its rivals' strategies.

As Bailey, Graham and Kaplan (1985) point out, there are three categories of airline costs, namely, overhead costs, flight costs and passenger costs. Flight costs and passenger costs vary with the number of flights and the number of passengers, respectively. Unit operating costs of the airlines are affected by a number of factors. These include input prices (such as cost of labour, fuel costs, airport charges), productivity and operational characteristics (Alamdari and Morrell, 1997). Operational characteristics include length of haul, passengers or cargo, schedule or charter service and so on. Other things being equal, higher the length of haul, lower is the unit cost (i.e., cost per kilometre). Productivity is measured by per unit of the input. So far as airline costs are concerned, labour costs generally account for 25 to 35 percent of the total operating costs.

Seven Freedoms and Cabotage

International air traffic is governed mostly by the Chicago Convention (i.e., Conference on the International Civil Aviation in Chicago in 1944). The Convention set the seven freedom categories. The First Freedom refers to the right of flying over another country without landing. The Second Freedom refers to the right of a technical stop in another country for refuelling or repairs. The Third Freedom refers to the right of taking on passengers or cargo in the airline's home country and to carry them to a destination in a different country. The Fourth Freedom is just the opposite of the Third Freedom. The Fifth Freedom refers to the right to take passengers or cargo from other countries and take them to a destination, which is not the airline's home country. The Sixth Freedom is the right to pick up passenger or cargo in a foreign country and to put down the traffic in another foreign country via the home country. The Seventh Freedom is the right to pick up passenger or cargo in a foreign country and to put down the traffic in another foreign country. The first two freedoms are routinely granted by most countries.

Another important right is cabotage where an airline of one country is allowed to operate flights entirely within another country. It is interesting to note that cabotage has not generally been allowed even after deregulation of air services in many countries even though foreign equity participation has been allowed in many cases.

Privatisation

In this section, we look at privatisation of national airlines. Airline deregulation has been accompanied by privatisation in many countries around the world. The national airlines of many countries started off as state airlines.

Good, Roller and Sickles (1995) provide a number of arguments why state ownership is not desirable. First, productive efficiency is unlikely to be achieved when ownership is in the hands of an entity, which does not have the lowest monitoring cost. Second, the experience of state ownership in many parts of the world shows that access to subsidy tends to dilute the perusal of the goal of achieving productive efficiency. Third, while the objective of the private companies is to maximise profit, the objectives of the state enterprises may be many-fold. These enterprises may seek to limit competition limit with other state enterprises. Thus, the lack of competition may reduce efficiency. State enterprises may also have the additional objective of providing employment. This tends to result in a higher employment level than is desirable from an efficiency point of view.

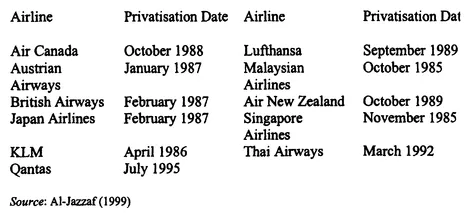

A list of major airlines that have been privatised along with their dates of start of privatisation are given in table 1.2.

It is interesting to note that there were no state airlines in the USA at any point in time. Many industrialised countries have privatised their national airlines. Many developing countries are following suit. Malaysia and Thailand have partially privatised their national airlines. Talks are underway in India for partial privatisation of the national airline - Air India. However, in many cases, privatisation does not mean that all the shares of the airlines are owned by private individuals and not by the government. For example, the major stakeholder in Malaysian Airlines is still the Malaysian government.

Al-Jazzaf (1999) examines the impact of privatisation on airline performance in ten countries. The impact of privatisation on the following six variables are studied: sales, net income, total assets, employment, capital expenditures and dividends. The study finds that net income, total assets and capital expenditures grew at a moderate rate after deregulation while sales grew quite rapidly. The increase in the median dividends is found to be not statistically significant. However, the initial period after privatisation is accompanied by administrative and financial restructuring costs (besides the increase in capital expenditure) and this tends to reduce profitability. Contrary to the popular belief, the study finds an increase in employment after privatisation.

Frequent Flier Programs

While airline deregulation tends to increase competition, frequent flier programs tend to increase brand loyalty. In a sense, this goes against promotion of competition. Those who join the frequent flier program of an airline earn points when they take flights on the airline or its subsidiaries and/or use credit cards issued by the airline or stay in hotels designated by the airline. These points can then be used to get free tickets, upgrades and in some cases, merchandise.

The alliances among the airlines for the frequent flier programs are often global in nature. The biggest such alliance is the Star Alliance initiated by the United Airlines. Many important airlines such as Singapore Airlines, Thai Airways, Cathay Pacific, Malaysian Airlines, All Nippon Airlines, Swiss Airlines and Austrian Airlines are part of the alliance. Data on the travel characteristics of the members of the frequent flier programs are often used by the airlines to obtain valuable information about the passengers. But, there is also a significant economic impact of the frequent flier programs. Frequent flier programs restrict competition by discouraging entry of the smaller operators and limiting the potential growth of the existing smaller operators. Greater the size of the alliances, higher is the adverse impacts on the smaller airlines. One of the reasons why both Ansett Airlines and Australian Airlines (which merged with Qantas in 1994) introduced frequent flier programs in 1991 was to drive Compass, the new airline, from the airline markets in Australia.

Airline Alliances

The alliances tend to foster global networks. Alliances among airlines have become an increasingly common feature among the various airlines in the world. The process of alliances started in 1990. The basic motivation behind alliances is to reap the benefits of consolidation in the absence of mergers, which are not allowed by most governments. These alliances can take many forms. These may involve joint fare determination, catering, baggage handling, flight scheduling, and frequent fliers. In some cases, it may also involve code-sharing where an airline can sell tickets for services to be provided by the partner's routes. These alliances can also be route specific or could be on a regional basis.

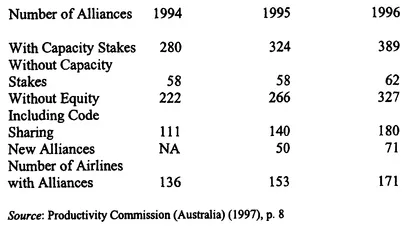

Table 1.3 looks at the growth of international alliances during the period 1994-96. The alliances are changing the character of competitiveness of the airline industry internationally. At last count, there were 579 bilateral partnerships involving the 220 main airlines. There are five major groupings at present. In addition, there are a host of bilateral joint-marketing deals. To some extent, the alliances have been undermined by deregulation, which has allowed mergers in some cases.

The first international take-over in Europe took place in 2000. The Belgian flag-carrier, Sabena was allowed to be taken over by SAir (which is the parent company of Swissair) by the European Union, Belgium and Switzerland. This merger could destabilise the Oneworld alliance of which British Airways and American Airlines are major partners (Anonymous, 2000a). Sabena has a separate bilateral alliance with American Airlines. SAir is a member of the European alliance named Qualiflyer alliance. Thus, American Airlines can now join Qualiflyer alliance. This will irritate British Airways. The proposed take-over of KLM by British Airways would mean that British Airways would be a part of the Wings alliance built around Northwest and KLM. But, such an event will make it more difficult for British Airways to continue to be a part of the Oneworld alliance.

Oum and Taylor (1995) discuss a number of advantages of such global networks. First, the potential benefits to consumers are lower joint airfares and a better quality of service due to less waiting time for connecting flights, higher service frequency, lower possibility of lost luggage and the faster accumulation of frequent flier points. Second, from the carrier's point of view, such a network is likely to increase efficiency. These include joint use of ground facilities, pooling of storage and maintenance facilities, joint buying of aircraft and other inputs and a leaner route structure made possible by the consolidation of networks by linking hubs to hubs and the avoidance of duplicate routes. These can result in a substantial increase in profit. For example, KLM announced that its alliance with Northwest would add around $150 million in additional profit. Similarly, Lufthansa gained an additional profit of $175 million in 1996 from its alliances with other airlines (Shifrin, 1997). Third, there are advantages to the carriers if we take into account the institutional and regulatory factors. The local carrier of a country has more knowledge of the institutional and regulatory arrangements as well as of the consumer preferences. In most countries, outright take-over of the airline by a foreign airline company is not allowed. Thus, networking is the next best thing.

However, as Gourdin (1998) points out, there are several disadvantages of alliances. First, some commentators have argued th...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry

APA 6 Citation

Sinha, D. (2019). Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1477820/deregulation-and-liberalisation-of-the-airline-industry-asia-europe-north-america-and-oceania-pdf (Original work published 2019)

Chicago Citation

Sinha, Dipendra. (2019) 2019. Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1477820/deregulation-and-liberalisation-of-the-airline-industry-asia-europe-north-america-and-oceania-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Sinha, D. (2019) Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1477820/deregulation-and-liberalisation-of-the-airline-industry-asia-europe-north-america-and-oceania-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Sinha, Dipendra. Deregulation and Liberalisation of the Airline Industry. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2019. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.