Introduction

In all societies, irrespective of their system of organization, or location in time and space, there are three basic modes by which conflicts are handled. These are; (a) violence and coercion, (b) various forms of bargaining and negotiations, and (c) the intervention of a third party. Third party intervention may be (i) binding, or (ii) non-binding. In the former case parties become merely petitioners or supplicants attempting to persuade a third party to give a favourable decision, in the latter they are assisted by a third party in the process of seeking a jointly acceptable decision.

Although the practice of third party intervention is probably as old as conflict itself, the subject has only very recently been studied systematically. Social scientists scarcely looked beyond detailed descriptions of single cases of intervention. The range and implications of third party activity were more often assumed rather than disclosed. Third parties, or mediators, as they are often called, have been depicted as being neutral and somewhat ineffective, or powerful individuals or states acting in a dictatorial manner. Both images haunted students of third party activity for far too long a time. Both are unsatisfactory images which need to be discarded or revised.

This book purports to take some steps toward developing a more accurate and relevant perception of the strengths and limitations of third parties in conflict situations. It approaches third party intervention with a broad, exploratory design. Its primary purposes are the presentation of a set of ideas about third party intervention, the evaluation of these ideas, and an examination of third parties’ behavior in several conflict systems, representing a wide variety of the forms of human existence. Although the book is concerned with providing knowledge that might later be applied, it does not carry with it a prescriptive label. It clarifies some aspects of a particular conflict management mechanism. It does not, though, offer a solution to the problems of social conflict, nor is it concerned with improving all systems for resolving conflict.

The main interest of the book - third party intervention in conflict situations - can be justified by (a) the paucity of such investigations and the lack of systematic knowledge concerning effective interventions, (b) the growing dissatisfaction with other, and costlier, forms of conflict management and, most significantly, (c) the need for innovative techniques of conflict management. The number of lethal conflicts and the extent of violence and destruction are on such a scale that unless we make some progress toward understanding conflict and the factors which can influence its course and outcomes, we may well fail to ensure the survival of homo sapiens.

We find ourselves today in a maze of conflicts; between individuals, groups, societies, and religions. Some of these conflicts may have a revitalizing effect, others may precipitate a confrontation with consequences which are too horrendous to contemplate. Some follow definite rules, others involve irrational and violent behavior. We can, at any rate, no longer remain impervious to the experience of conflict or the reality of human existence. “Ours is a dangerous age in which the race between creative knowledge and destruction is closer than ever before. Destruction has not yet arrived and knowledge still has a chance. Those of us who have scientific training and ability should do everything in our power to speed up creation and slow down destruction.” (Scott, 1958: 134).

With this in mind, the book is conceived as an effort in generating socially useful knowledge, in particular knowledge about the nature, role, and functions of third parties. I do not assume that such knowledge will enable us to move apparently intractable conflicts toward a solution. It should, though, help us to move toward a better understanding of the third party process. Knowledge of conflict management, it is true, does not guarantee successful experience; lack of knowledge, on the other hand, probably precludes such experiences.

Knowledge of the many roles and functions that third parties provide and the factors that contribute to their effectiveness can be, and hopefully will be, instrumental in promoting the values of peace, balance and conflict resolutions. These values are central to the whole approach. For this reason they are articulated explicitly, rather than allowed to creep in stealthily.

A precondition for such an approach is conceptual clarity and a measure of verbal precision. If we seek to describe a range of behavior, we must begin by observing the obvious need to distinguish it from other phenomena. This is particularly important in the case of conflict, for as Boulding reminds us, conflict “is found almost everywhere. It is found through the biological world, where the conflict both of individuals and of species is an important part of the picture. It is found everywhere in the world of man and all the social sciences study it.’ (Boulding, 1962:1). What, then, is conflict? What are the factors which affect it, and what is the place of third parties in the management of conflict?

The Nature of Conflict

In everyday language conflict denotes overt, coercive interactions in which two, or more, contending parties seek to impose their will on one another. Fights, violence, and hostility are the terms customarily employed to describe a conflict relationship. The range of conflict phenomena is, however, much wider than that implied by its physical connotation. It is used to describe inconsistencies as well as the process of trying to solve them; it has physical and moral implications; it embraces opinions as well as situations and a wide range of behavior. Conventional usage of the term is inconsistent with the full range of conflict phenomena.(1)

In attempting to analyze conflict phenomena, particular attention has to be paid to the term itself, to the explicit and implicit judgements that are made about it (e.g. is it ‘good’ or ‘bad’?) and to efforts to distinguish it from related, if distinct, events (e.g. tension, war, hostility, etc.). Most perspectives on social conflict are etymological, or they may be classified as either ‘actor-oriented’ or ‘system-oriented’. From an actor-oriented perspective conflicts are necessary, indeed inevitable; from a system-oriented perspective conflicts may be undesirable (because they may interfere with the goal of system maintenance). Combining these perspectives provides a useful context for my own approach to conflict.

Narrow Approaches

Park and Burgess (1924) offer a definition of conflict which identifies it as a conscious, intermittent struggle for status. Lewis Coser (1956), who offered one of the most influential definitions of conflict, regards it as a struggle over values, entailing behavior that is initiated with the intent of inflicting harm, damage, or injury on the other party. Although the interests of actors have not been foresworn, both these definitions are essentially within the system orientation.

The conception identifying conflict with violent interactions in which behavior and perceptions are in opposition has remained a basic conception in conflict studies. Mack and Snyder (1957), without offering a specific definition, identify the distinguishing characteristics of the range of conflict phenomena as:

- the existence of two or more parties

- their interaction arises from a condition of resource scarcity or position scarcity

- they engage in mutually opposing actions

- their behavior is intended to damage, injure or eliminate the other party

- their interactions are overt and can be measured or evaluated by outside observers

Conflict, within this approach, is contrasted with cooperation. It denotes not only differences of opinion, but the demonstrable coercive means utilized by parties with a difference of opinion.

Wider Approaches

The narrow, and more precise, approach to conflict is not shared by all researchers. If we are interested in the relationship between social systems and social conflicts, we have to adopt a much wider focus and study those structures or situations which promote mutually incompatible interests or values. Dahrendorf (1959), for instance, suggests that conflicts are present whenever people have differential access to power and authority. Curie (1971) widens the conception of conflict phenomena by asserting its presence in any situation where human beings are being impeded from realising their potential (however that may be defined).

Wider approaches to conflict are not so much concerned with the disruptive features of conflict as they are with the dimensions of a social structure and the conditions which give rise to parties with incompatible goals. They study the nature of resources and the structure of their distribution. Wider approaches to conflict do not assume that a given system’s survival is necessarily beneficial, nor do they refer to conflict as deviation, unhealthy, or pathological. Conflict calls attention to the latent problems of a system.(2)

A strong case can be made for either conception. Whether we discuss conflict in terms of behavior, or in terms of a situation, whether we analyze it empirically, or write about it metaphysically, is ultimately dependent upon the purposes and epistemology of the analyst. Values affect the labels we give and determine the ‘facts’ we select. Conflict can be most profitably examined only when we are aware of the different perspectives and the fundamental assumptions that dominate each perspective.

Subjective Approaches

A question which has preoccupied conflict researchers for some time, and one to which no clear answer has been given, concerns the extent to which conflict can be understood as a subjective or objective phenomenon. Subjective approaches to conflict assert that, at the most basic level, conflicts are about values and values are ultimately dependent upon perceptions. Hence, conflicts are subjective and the parties’ perception of the values in conflict is, in the final analysis, all that counts.(3) The parties’ perception transforms a situation into a conflict situation, and it can also transform a conflict from one of violence and coercion into one with mutually beneficial outcomes (Burton, 1970a).

The view that conflicts are primarily subjective (i.e. perceptual) is tenable if we accept that disputed values are not absolute or in fixed supply. That they may be increased, changed, redefined, or transformed in the course of conflict interactions. If conflict actors could somehow be brought, through a third party perhaps, to a greater awareness of their perceptions and predispositions, then opposed values may well change to collaborative values. Subjective approaches to conflict are concerned with the parties’ orientation and with devising tools and strategies for rectifying conflict-producing misperceptions.

Given this approach, a situation may be regarded as a conflict situation if, and only if, the adversaries perceive that they are in conflict. From a concern with underlying structural relations, we have moved to a concern with the parties’ awareness and definition of a situation.

Objective Approaches

Opposed to this view is the approach which asserts that conflicts exist whenever there are incompatible interests, irrespective of whether or not the actors are aware of these interests. Where subjective approaches to conflict emphasize motivational and attitudinal factors, objective approaches stress structural and predispositional factors. With a different focus on conflict phenomena, it is not surprising to note that each approach offers its own mode of conflict resolution. The former sees conflict resolution as entailing a change in perceptions, the latter argues for a fundamental restructuring of social situations (see Schmid, 1968).

This kind of approach takes on normative elements or implications. The scholar, analyst, or observer defines, in his own terms, the existence of a conflict situation (‘the happy-slave syndrome’). An ‘objective’ conflict is said to exist when actors find themselves in a situation which engenders mutually incompatible goals (e.g. labor-management). Neither conflict behavior nor hostile attitudes need be present (the actors may, after all, suffer from ‘false consciousness’). The existence of a presumed goal incompatibility is, according to this approach, a sufficient reason for defining a social situation as a conflict situation.(4)

An objective approach to conflict defines a conflict in the analyst’s own terms, not the parties. It is an approach which is concerned with the contradictions contained within any social structure and the extent to which distinct groups develop incompatible goals as a result of these contradictions.

Toward a Conception of Conflict

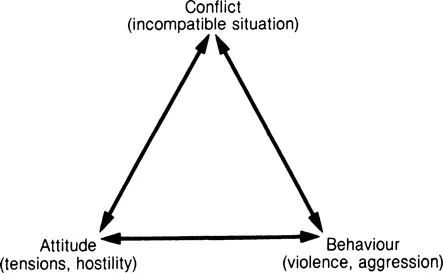

This short, and far from comprehensive, exposition serves to show us just how ambiguous, and complex, the concept of conflict can be. The conceptual division along the objective v. subjective and narrow v. wide dimensions is but one of few possible divisions. In an effort to synthesize the different strands and components of a conflictual relationship, we draw upon Galtung’s conflict triangle (see Galtung, 1971:125). This, to my knowledge, offers the only satisfactory formulation of conflict which allows us to examine (a) a specific conflict situation, (b) motives and the parties’ cognitive structure, and (c) the behavioral-attitudinal dynamics of a conflict process.

Instead of a simple definition of conflict, Galtung offers us a format of three inter-related conflict elements, which can be considered jointly or separately. These elements can be illustrated by a simple triangle as in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Galtung’s Conflict Triangle

A conflict situation, corresponding to the wider or objective approaches to conflict, refers to a situation which generates incompatible goals or values among different parties. Conflict attitudes are closer to the subjective approach to conflict, consisting of the psychological and cognitive processes which engender conflict or are consequent to it. And conflict behavior consists of actual, observed activities undertaken by one party and designed to injure, thwart, or eliminate its opponent (this corresponds to the narrow approaches to conflict).

The conception of conflict in terms of its three interrelated components clarifies the term, directs our attention to the various conflict sources (e.g. frustration as a source of conflict attitudes), makes it apparent that a wide variety of situational factors (e.g. norms, rules, constituents etc.) affect conflict behavior and attitudes and, more importantly for our purposes, it encourages us to propose better schemes of conflict management. Unless we are clear about confli...