eBook - ePub

The Sri Lankan Tamils

Ethnicity And Identity

Chelvadurai Manogaran, Bryan Pfaffenberger

This is a test

Share book

- 247 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Sri Lankan Tamils

Ethnicity And Identity

Chelvadurai Manogaran, Bryan Pfaffenberger

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Within the larger context of bitter ethnic strife in Sri Lanka, this timely volume assembles a multidisciplinary group of scholars to explore the central issue of Tamil identity in this South Asian country. Bringing historical, sociological, political, and geographical perspectives to bear on the subject, the contributors analyze various aspects of

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Sri Lankan Tamils an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Sri Lankan Tamils by Chelvadurai Manogaran, Bryan Pfaffenberger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Sri Lankan Tamils

Bryan Pfaffenberger

The chapters to follow represent the first sustained attempt to comprehend the ethnic identity of the indigenous Tamil people of Sri Lanka, as that identity has been formed, and finally forged in bloodshed and fire, through the Tamil community's years of change and crisis.

By now, certainly, there are few who have not heard of Sri Lanka's bloody and protracted ethnic war, the conflict between the Sinhalese-dominated central government and various militant Tamil groups fighting for Tamil rights in a Sinhalese-controlled nation. A highly effective militant group, known as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), fight the government in a bid to win a separate Tamil state (Tamil Eelam), comprising the present Northern and Eastern Provinces of the island country. More than 30,000 people--among them Tamil and Sinhalese innocents caught in the crossfire--have been killed since the outbreak of organized violence in 1974. The war has devastated the Tamil-dominated north and east and compelled half a million Sri Lankans, most of them Tamils, to leave the country. Seemingly incapable of resolution, the conflict has earned Sri Lanka the unenviable epithet "the Beirut of South Asia."1

A brief review of its tragic history follows, with particular emphasis on the role and the fate of the Sri Lanka Tamil community. But this book's focus is more narrow--the changing ethnic identity of the Sri Lanka's Tamils, and the role this changing identity has played in shaping the course and nature of the conflict in Sri Lanka--so this Introduction turns to an assessment of the role ethnic identities can play in conflicts of the Sri Lankan sort, and to an overview of this book's contributions.2

Dimensions of a Misunderstanding

Over the years of the Sri Lankan conflict, I have observed a depressing trend. In the early years, it took only one or two deaths to trip whatever sensor is deployed to allocate space in the Washington Posts and New York Times of the world, but soon it was a dozen, and then twenty-five, and then fifty, and now more than one hundred. Surely the explanation can be found in the fact that Sri Lanka isn't news anymore; the world has become accustomed to people dying there. (The various parties to the conflict exploit this fact without shame, out of the conviction that they possess a certain latitude within which they can operate with impunity.) But a contributing factor is the sheer amount of columnar space that must be allocated to explaining this mysterious conflict, far away in a country that few Americans have even heard of, let alone located on a map. (But then again, more than one-third of U.S. high school students cannot even locate their own country on a map--a fact that newspaper editors appreciate only too well.)

And so the tedious explanation begins, requiring a column or more. The Sri Lanka Tamils, we are told, are the descendants of racially "Dravidian" migrants from south India. They are predominantly Saivite Hindus, and speakers of the Tamil tongue of the Dravidian family, so widely spoken in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Dwelling in the dry Northern and Eastern Provinces of the island, they stand in almost perfect geographic, racial, linguistic, and religious contrast to the Sinhalese, who dwell in the lushly-watered southwest, trace their descent from "Aryan" (North Indian) immigrants more than two thousand years ago, speak the Sinhala language (an Indo-European tongue), and are predominantly Theravada Buddhists. One goes on to imagine that Sri Lanka could only be an artificial nation, one whose boundaries emerged at the convenience of the European colonial powers, and whose constituent ethnic groups had little or nothing to do with each other prior to their forced colonial unification. This was precisely the view of the early English in Sri Lanka, as evidenced by the words of Hugh Cleghorn, Colonial Secretary of Ceylon in 1799:

Two different nations, from the very ancient period, have divided between them the possession of the island: First the Cinhalese, inhabiting the interior of the country in its southern end and western parts from Wallouve to that of Chilow, and secondly the Malabars, who possess the northern and eastern districts. These two nations differ entirely in their religion, language, and manners.3

We fit Sri Lanka into a broader narrative of Balkanization, a racialist narrative in which artificial countries, held together only by force, collapse in hatred and war as soon as democracy arrives.

How can one stand in the way of a mythos of such power? And it is doubly difficult to dislodge, for the parties to the Sri Lankan conflict have themselves appropriated it, made it their own, made it a weapon of hatred and killing. But it is wrong, in virtually every respect.

"There is nothing about the traditional cultures of the Tamil and Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka that prevent them from living in amity." Far from isolated in precolonial times, the Tamil and Sinhalese peoples of Sri Lanka were in sufficiently close communication to have deeply influenced the sentence structure of each other's languages, the minutiae of their strikingly similar kinship classification systems, the structure and organization of their caste systems, and the details of village rituals. To be sure, the two groups dwelt in separate territories, as Cleghorn observed: the Sinhalese in the south and west, and the Tamils in the east and north. But it was precisely because the two groups dwelt in amity for so long that their cultures bear some remarkable similarities to one another, similarities that are lost on the likes of Cleghorn--no less than to the extremists of today--but obvious to an anthropologist. The truth is that, viewed anthropologically, the Tamil and Sinhalese peoples of Sri Lanka are much more similar to each other than either group is to any of the peoples of India, northern or southern. The similarities between the Tamil and Sinhalese peoples of Sri Lanka, unappreciated today, were not lost on previous generations of Sri Lankans, nor even on the Tamils of 70 years ago--S. Rasanayagam, in his Ancient Jaffna (1926), cheerfully propounded the notion that the Sri Lanka Tamils were more like the Sinhalese than south Indians--a view recently castigated by LTTE hardliners.

It is true that Sinhalese Buddhist texts, most notably the Mahavamsa and Culavamsa, recount a legacy of ancient hatred and struggle between the Sinhalese and conquering Damilas (south Indian Tamils), who repeatedly contested the Sinhalese for control of Rajarata, the north-central "Land of Kings." But it has only been in the last century that the Sinhalese started to draw a connection between the detested Damilas of the texts and the Tamils dwelling peaceably in the north and east. As against those who would read these texts to infer a deep-seated Sinhalese hatred of all Tamils, it is apparent from recent scholarship--admirably summarized by S.J. Tambia4--that the connection between the Damilas of the text and the Tamils of the north had to be deliberately and repeatedly constructed, and this took place within the last century. Indeed, the history of Sri Lanka throughout the colonial period is remarkable for the absence of ethnic conflict qua ethnic conflict,5 with the notable exception of the 1915 Buddhist-Muslim conflict--in which, to testify to the newly-constructed character of Sinhalese-Tamil conflict, the Tamil leadership took the side of the Sinhalese.6 As outrageous as it may seem to those who, whether Sri Lankan or not, have taken sides in this conflict, it is reading history backwards to suppose that today's problems stem from yesterday's divisions. They are of recent origin.7

The Tamil Speakers of Sri Lanka: Fragmented and Peripheralized in a Centralized State

When the European colonial powers contacted Sri Lanka in the sixteenth century, they found three indigenous kingdoms: a Tamil Hindu state in the Jaffna peninsula, a Sinhalese kingdom in the central highlands at Kandy, and a second Sinhalese kingdom near the western coast. With kings claiming descent from the Brahmans of Rameshwarem, the Jaffna kingdom received a visit from the famed Arabian explorer Ibn Batuta, who wrote of the king's overlordship of the pearl fisheries of Mannar.8 In the vast north-central plains and along the eastern coasts, chiefs called Vanniyar held sway, playing off the various kingdoms to their advantage.

The Tamil kingdom was among the first to fall to European colonial initiatives, which were to dominate the island's politics for more than three centuries. The Portuguese (1505-1638) effectively converted many of the coastal fishing peoples, who had low status in traditional Hindu and Buddhist ranking systems, to Catholicism, and brought down the last Hindu king of Jaffna in 1619, Following on their heels were the Dutch (1638-1796), who strengthened indigenous labor exploitation to favor the development of plantation agriculture. By 1815, the British (1796-1948) had subdued the sole remaining indigenous kingdom, the Kandyan kingdom, and imposed a colonial administration on the entire island. Ceylon, as it was known then, became a Crown Colony, a model colony in many respects, and thousands of Englishmen settled In the central highlands to grow coffee and, later, tea. In the twentieth century, remittances from profitable tea exports allowed Ceylon the luxury of financing an extensive rural welfare system which, in tandem with an exceptionally late start on industrialization, resulted in one of the twentieth century's lowest rates of rural-urban migration.

With the exceptions of a significant increase in the proportion of Sinhalese residing in the Eastern Province and the rise of a large Tamil settlement in Colombo, Sri Lanka's ethnic geography has not changed appreciably since colonial times. The Sinhalese, mainly Theravada Buddhists and speakers of the Sinhala language, related to languages of north India, dwell in the southwest, while the indigenous Ceylon Tamils, mainly Saivite Hindus and speakers of the Tamil tongue widely spoken in south India, dwell in the Northern and Eastern Provinces. A group of Tamil-speaking Muslims, the Ceylon Moore, comprise about half of the indigenous Eastern Province population but has strong ties to trading communities situated throughout Sinhalese towns and cities. The one major exception to the preservation of the precolonial pattern is the presence in the central highlands of a large community called the Indian Tamils, descendants of agricultural laborers imported by the British to work in the tea plantations. The citizenship of the Indian Tamils has long been an issue between Sri Lanka and India and agreements to repatriate

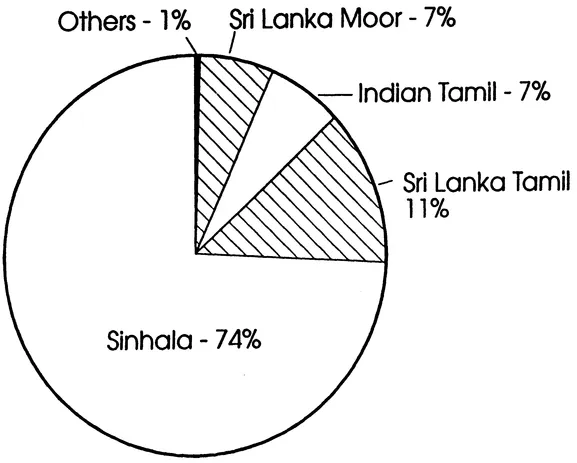

FIGURE 1.1 Ethnic Divisions of Sri Lanka

TABLE 1.1 Ethnic Divisions of Sri Lanka, 1993 (in percentages)

| (in percentages) | |

| Sinhala | 74 |

| Sri Lanka Tamil | 11 |

| Indian Tamil | 07 |

| Sri Lanka Moor | 07 |

| Burgher, Malay, Vedda | 01 |

Source: CIA World Fad Book, 1993

some Indian Tamils to south India while granting others Sri Lankan citizenship have been implemented only slowly.

Speakers of the Sinhala language are overwhelmingly predominant numerically; they constitute 74 percent of the island's population (See Figure and Table 1.1). If one adds together all the speakers of the Tamil tongue in Sri Lanka, fully one-fourth of the population speaks Tamil--but there are several Tamil- speaking communities with conflicting interests, and Tamil speakers in general had never until the passing of the Sinhala Only Act in 1956 attempted to unify themselves in defense of the rights of speakers of the Tamil language in Sri Lanka. The Tamil-speaking peoples of Sri Lanka are officially categorized as follows:

- - The Sri Lanka Tamils, descendants of the indigenous Tamil settler the north and east, comprise approximately 11 percent of the population. However, this group is subdivided into two traditional groupings, the Jaffna Tamils (the Tamils of the Jaffna peninsula and of the Northern Province) and the Batticaloa Tamils (the Tamils of the eastern coastal region). Intermarriage was traditionally not usual between the two communities unless the parties concerned belonged to the same caste group. Like the natu regions of Tamil Nadu, the contrasting regional identities of Jaffna and the eastern coastal region can be attributed to the integrating influence of differing dominant castes: the Jaffna Tamil social structure is focused on the preeminence of the Vellalar caste, while the east coast region's markedly different social structure revolves around the dominant Mukkuvar. In kinship and marriage, too, the regions differ. In Jaffna, kinship is traced bilaterally, while the eastern coastal region retains one of the world's most interesting matrilineal kinship structures (a structure shared with the Tamil-speaking Muslims of the eastern coastal region). In 1977, Sri Lanka Tamil voters in the north and east strongly supported candidates of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) in what that party described as a referendum on the peaceful partitioning of Sri Lanka, with the current Northern and Eastern Provinces forming an independent Tamil nation called Tamil Eelam. Support was very strong in the Northern Province, but somewhat less so in the East, where Batticaloa Tamils have occasionally expressed concerns that they would suffer discrimination in a state controlled by the Tamils of Jaffna. In addition to the northern and eastern Sri Lanka Tamil communities, there is a large Sri Lanka Tamil neighborhood in Colombo, in Wellawatta, the residents of which would almost certainly suffer if partition were to occur.

- - The Indian Tamils, descendants of Indian plantation workers brought to the island's central highlands by British tea plantation owners, comprise approximately 8 percent of Sri Lanka's population. The citizenship of the Indian Tamils has long stood as an issue in Sri Lankan-Indian relations; a series of bilateral agreements calls for the repatriation of some Indian Tamils to south India, with others receiving Sri Lankan citizenship, but implementation of these agreements has been slow. With no real ties to the indigenous Tamils of the north or east, the Indian Tamils concern themselves w...