- 102 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

While it is increasingly clear that adult obesity begins in childhood, preventing this condition is a major challenge for the pediatrician.

Adult Obesity: A Paediatric Challenge highlights the causes and consequences of obesity, bringing a modern understanding to the treatment of a heavily stigmatized problem. This collection of essays, base

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adult Obesity by Linda Voss,Terry Wilkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Nutrizione, dietetica e bariatria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The issue

1 Obesity: a global problem

Philip James

Introduction

The first ever report on obesity by the World Health Organization (WHO) was published in December 2000 (World Health Organization, 2000). It was based on an expert technical consultation, which convened in 1997, after a draft report had been produced by the International Obesity TaskForce (IOTF) with its eleven subcommittees of experts from across the world. Originally, WHO had not considered obesity important because its role, in particular, was to help the developing world, and it was assumed that obesity only affected affluent societies. The prevailing prejudice that individuals were to blame for over-indulging themselves or being slothful clearly influenced WHO officials’ rejection of the problem. This approach was in no way unusual. Obesity has long been considered of little importance by doctors, who usually find their obese patients difficult to manage and concerned about what seems to be a cosmetic problem. In practice, it has now become clear that we are in the middle of a global epidemic of an important disease affecting both children and adults. The challenge now is to produce coherent data to highlight the problem and seek solutions for its prevention and management.

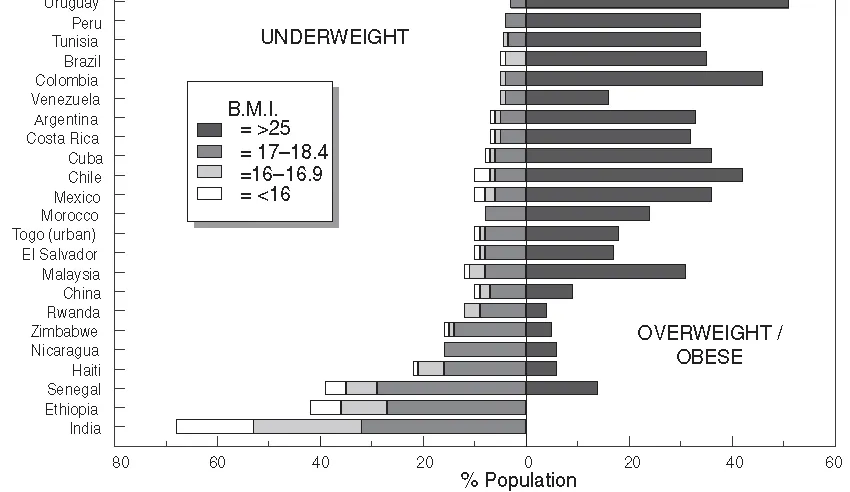

In the mid 1990s, WHO undertook an evaluation of underweight and overweight in both children and adults (World Health Organization, 1995). At that stage the problem of chronic energy deficiency in adults was being recognized for the first time (James et al., 1988), but when representative data were obtained from a number of countries it soon became evident that underweight or ‘chronic energy deficiency’ of adults was comparatively unusual and that many developing countries had a far greater problem of excess weight (Figure 1.1). For this analysis the standard measure of body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was used and, in order to accommodate the problem of underweight in adults, it was recognized that the lower limit of the normal range of BMI should be extended to 18.5 (Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 BMI distribution of adult population from surveys worldwide. Reproduced with permission from WHO (2000).

Table 1.1 WHO classification of obesity (BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2)

The problem with only worrying about individuals categorized as overweight if their BMI is over 25.0, and coping medically with patients as ‘obese’ once they have a BMI of 30.0 or more, neglects the fact that there is a distribution of BMIs within the population and that, as the epidemic grows, the whole population’s distribution of BMIs is shifting upwards. Thus there is an extraordinary increase in obesity rates with seemingly modest increases in the average BMI of a population (Rose, 1991). In the early 1980s, China had a beautiful gaussian distribution of BMIs with an average of about 21, and only a small proportion of underweight and overweight adults. Compare this with the United States, where the average BMI of the population is over 25 and obesity rates are currently 30 per cent or more. These countries display the two extremes of a spectrum, but it is now clear that a dramatic shift to the right is occurring with escalating obesity rates throughout the world.

The disease burden of obesity

The hazards of a weight increase have been underestimated because, traditionally, epidemiologists have simply regarded weight gain as one of the risk factors affecting blood pressure, the propensity to diabetes and dyslipidaemia. Thus the risks of cardiovascular disease were ascribed to hypertension and dyslipidaemia, rather than to an underlying driver, that is, unhealthy weight gain. What is now evident is that, even within the so-called normal range of BMI, there is a markedly increased risk of type 2 diabetes as BMI rises. The risk is minimal when BMIs are held at about 20 and with no weight increase in adult life. By the time adults have reached a BMI of 25, both men and women have a five- to six-fold increased risk of diabetes and this risk escalates further at higher levels of BMI (Willett et al., 1999). The risk of hypertension also rises rapidly but one of the most intriguing features is the progressive reduction in blood high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels once the BMI starts rising above about 20. A low HDL cholesterol is one of the most powerful predictors of the risk of coronary heart disease and Shaper and colleagues, conducting the British Regional Heart Survey (Shaper et al. , 1997), found marked falls in HDL with substantial increases in total cholesterol, serum triglycerides and blood pressure in adult men even before they were outside the normal BMI range. By the time British middle-aged men reach BMIs of 30, a third of them have hypertension.

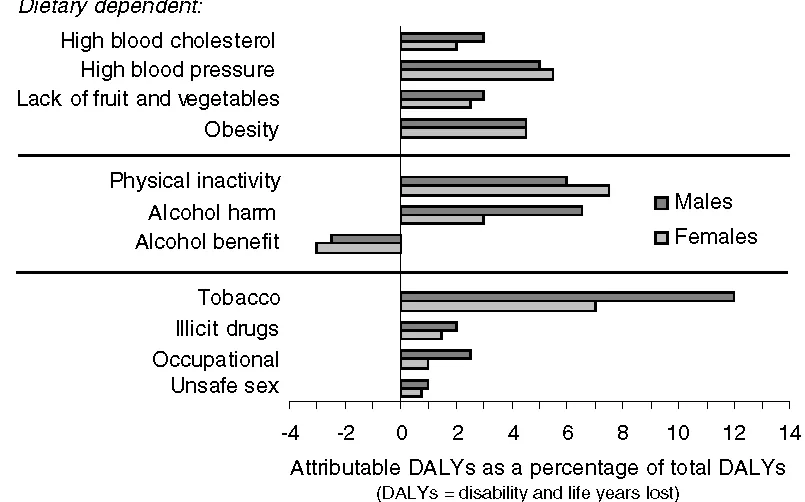

New approaches to assessing the burden of disease linked to obesity are now being published. A recent Australian study (Mathers et al., 1999) assessed the total burden of disease in terms of the number of years of life lost and the number of years lived in a disabled state (disability adjusted life years or DALYs), and assessed the likely contributors to the major diseases affecting Victoria state in Australia. Figure 1.2 reveals that diet and physical inactivity account for a greater burden than that imposed by tobacco and, even in these analyses, the burden from obesity was arbitrarily halved to take account of the potential impact of physical inactivity in precipitating overweight and obesity. The same study also showed that the burden of disease expressed in DALYs increased with age and became substantial in middle-aged women.

Martorell et al. (2000) recently assessed the overall prevalence of overweight and obesity in women from different parts of the world, and the extent of the global epidemic is very clear. Although North American women have major problems of obesity, to everyone’s surprise, the overall figures are matched by those from the ex-command economies, that is, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, and exceeded by the rates of overweight and obesity in women living in the Middle East. The IOTF has been conducting similar analyses on men as well as women, and estimates that there are about 315 million obese adults in the world and about three-quarters of a billion who are overweight. This therefore represents an extraordinary disease burden.

Figure 1.2 Proportion of total burden of disease attributable to selected risk factors, by sex, Australia 1996 (Source: Mathers et al., 1999).

Asian sensitivities to obesity-related morbidity

Although Asians are classified, using standard WHO criteria, as not having an appreciable problem of obesity, a group of experts led by Professors Zimmet and Inoue from Australia and Japan, met in Hong Kong under the auspices of WHO, the International Association for the Study of Obesity (IASO) and the IOTF. On the basis of their assessments of preliminary data from Hong Kong and Japan, they suggested that adult Asians could no longer be classified in BMI terms in the same way as the rest of the world (WHO/IASO/IOTF, 2000). They proposed that in people of Asian origin the upper limit of a normal BMI should be 23, and that a BMI of 25 should trigger the diagnosis of obesity. This new development is obviously contentious because, hitherto, when dealing with children’s growth, the WHO has studiously avoided considering local growth standards, particularly when it became evident that Third World children brought up in a hygienic, well-fed and nurturing environment grew at rates equivalent to WHO standards.

The question, therefore, is whether people of Asian origin are genetically different, or whether they simply display an unusual sensitivity to diabetes and hypertension because of some prevailing nutritional or other environmental problem. It is clear, however, that there are differences between ethnic groups in their susceptibility to diabetes. This could reflect not only the impact of environmental factors such as diet on insulin resistance, but also the effects of dietary and other factors which alter the pancreatic capacity to secrete insulin. Type 2 diabetes emerges when the pancreatic capacity is unable to meet the long-standing demands made when overweight and obese adults develop insulin resistance and require a far greater endogenous output of insulin from the pancreas as it ages. Comparable data on the propensity to diabetes in adults with measured glucose intolerance have now shown that Scandinavian Caucasians have a rate of developing type 2 diabetes of about 5–6 per cent per year. In China, however, the comparable value, despite lower BMIs, is a 15 per cent conversion rate per year (Pen et al., 1997) These differences are mirrored by clear evidence that Mexican Americans and Hispanics have much greater prevalences of diabetes at the same body weights as white Americans living in the United States (Edelstein et al., 1997).

Early influences on adult disease

It has been well recognized that adults are much more liable to develop diabetes if they were already obese in childhood and entered adult life in an obese state. Further weight gain in adult life, which is then likely, amplifies the risk and it becomes 80- to 100-fold greater than that observed in adults who mature with a BMI of 20 and gain no further weight. This is a clear demonstration of the importance of early adiposity in precipitating the onset of type 2 diabetes (Colditz, 1995). Earlier risk factors are also evident: babies born to diabetic mothers tend not only to be larger than normal, but also to have a much greater propensity to developing type 2 diabetes, even in adolescence.

More intriguing, however, is the increasing evidence that fetal exposure to poor maternal nutrition may alter the pancreatic capacity of the child to cope subsequently. Barker (1994) has developed an hypothesis, based on very coherent experimental animal data, showing that animals born to mothers whose diet has been restricted in protein have pancreatic changes which reduce their capacity to generate insulin, and hepatic structural alterations which change gluconeogenesis and cholesterol metabolism. In primates as well as rodents it has been clearly demonstrated that the maternal diet and/or immediate post-natal diet can permanently alter the sensitivity of the offspring in terms of cholesterol metabolism and long-term body size. Barker proposed that analogous conditions occurred in man, and that babies born small were particularly likely to display higher blood pressure, a propensity to diabetes and coronary heart disease some 50 to 60 years later. This hypothesis was considered controversial because it might wrongly be implied that the children were doomed to chronic adult disease when in fact the experimental data suggest that the fetal changes mainly affect the propensity to respond to dietary and other changes in late life. Nevertheless, in his original studies of Hertfordshire men, Barker showed a progressive increase in the risk of abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome of diabetes, high blood pressure and abnormal lipids, the lower the weight of the men at birth.

There is also increasing evidence of an association between small babies and stunted growth in early childhood (James et al., 2000) and stunting has now been clearly linked to a greater likelihood of developing abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome in later life (Schroeder et al., 1999). A plausible hypothesis is that poor fetal nutrition limits the placenta’s capacity to metabolize circulating maternal cortisol. This then passes to the fetus, thereby amplifying fetal cortisol levels and resetting the fetal hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis. Thus there may be subtle hypercorticolism induced by fetal experiences which, as seen in clinical Cushing’s disease, alters the distribution of fat, channelling it to the abdomen. Here, it is considered to be particularly hazardous perhaps, in part, because a large release of fatty acids then enters the portal circulation which normally does not carry an excess to the liver.

Data from India now reveal that although about a third of babies are born small with low birth weight (<2.5 kg), they have an additional handicap in that they already have, probably because of poor maternal diets, less lean tissue and more body fat than normal. If they subsequently grow well, these small babies, by the age of 8 years, already display higher blood pressures and insulin resistance than normal children (Yajnik, 2000). Indians, whether in India or the UK, have a greater propensity to abdominal obesity, and 12 per cent of Indian adults in the Indian slums are diabetic, with a further 18 per cent glucose intolerant. This extraordinary epidemic of diabetes is occurring when adults have BMIs of only 23 or 24.

Among a total of some 400 million Indian city dwellers there is already a massive, largely unrecognized, public health problem. Glucose-intolerant and diabetic young women are, in turn, likely to ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I The issue

- Part II Nature and nurture

- Part III Opportunities and threats

- Part IV The challenge