eBook - ePub

The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990

Profits, Populism and Petroleum

Steve Isser

This is a test

- 486 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990

Profits, Populism and Petroleum

Steve Isser

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, originally published in 1996, traces the development of US government policy toward the oil industry during the 1920s and 1930s when the domestic syustem of production control was established. It then charts the deveopment and collapse of oil import controls, and the wild scramble for economic rents generated by Government regulation. It discusses the two oil crises and the 'phantom' Gulf War crisis, and the importance of public opinion in shaping the policy agenda. It also provides an in-depth study of Congressional oil votes from the 1950s to the 1980s and the formation of oil policy, beginning with theories of economic regulation, the role of interest groups in developing the policy agenda and the role of money in politics.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990 an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990 by Steve Isser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Industria energética. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Development of the System of Control

The US Oil Industry after World War I

The roots of the struggle over oil imports in the 1950s can be found in the emergence of the modem US oil industry in the 1920s. Independent producers had been at the heart of the industry from its beginnings in Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century, but the economics of petroleum led to the growth of large integrated firms, especially after the break-up of the Standard Oil Trust. After WWI the major oil companies became international, integrated giants (Exxon, Mobil, Texaco, Chevron, and Gulf), while a second tier of major companies emerged during this period. It would be these second tier companies who would undermine attempts at accommodation during the 1950s between the Majors and the independents. Finally, the cycle of recurring gluts on the market during the 1920s, by driving prices down and stocks up to the point where even the integrated firms wanted regulation, would result in the formation of the prorationing system. It was the need to protect this system of production control, and those interest groups whose fortunes were tied to it, that would prompt the Eisenhower Administration to establish restrictions on the importation of oil.

From the beginning the industry was characterized by a cyclic pattern of boom and bust, with most of the risks incurred by producers, especially independents. The producers’ weakness was due to a combination of physical and legal factors. Oil in a reservoir usually flows under pressure partially supplied by associated gas. When a well is drilled oil flows to it from regions of higher pressure in the reservoir. At the same time the land above most oilfields is owned by numerous landowners. Given the ease of obtaining leases and the low cost of drilling in the shallow oilfields which were the first to be discovered there were few barriers to entry for oil producers. Once the producer had purchased a lease or the landowner realized that he had oil under his property he was obliged to drill and produce oil as quickly as possible since otherwise it would flow to competitors’ wells. The courts made this situation a permanent feature of the industry with a number of rulings in the 1880s and 1890s establishing the “rule of capture.” This doctrine of property rights made petroleum analogous to wild game, granting ownership to the landowner or lessee who produces the oil regardless of its point of origin.1

The rule of capture would have a strong influence on the structure of the producing sector of the petroleum industry. The basic pattern was a spasm of overproduction in newly discovered fields, followed by a rapid decline in output as reservoir pressure was depleted. The reason for this production cycle was twofold: the common-property nature of oil reservoirs under the rule of capture and the lack of available credit for the small producer. Under the rule of capture the firm is affected three ways: (1) the value of a unit of reserves declines since if it is not produced today it may not be available tomorrow; (2) there are rapidly increasing marginal costs of production as other firms deplete the reservoir, independent of the individual firm’s production decision; (3) given the surge in production, unless the reservoir is amply served by suitable transportation (i.e., pipelines) the high marginal cost of transporting surge production to markets will cause the price at the wellhead to decline even when this additional production is insufficient to effect market price.

The first two factors encouraged each firm to maximize its short-run level of production, usually at the expense of long-term production from the reservoir and certainly with regard to the optimal path of production. The third factor left the small producer at the mercy of the larger companies. Most small producers had limited capital and no collateral and were unable to invest in storage facilities. The larger companies, aware of the inability of the small producer to transport his production to markets, would invest in storage facilities near the newly discovered fields, buy oil at depressed prices, and wait until the production surge ended with the drop in reservoir pressure. The cost of storage was usually far less than the eventual rebound in prices, providing a handsome profit without incurring the risks of exploration. These companies would also buy out producers during the period of lowest prices, obtaining producing properties at bargain prices.

The low cost of drilling wells to the shallow depths of the early fields allowed the small wildcatter to survive during this period. In 1922 wells were commonly drilled at a cost of $40, 000 to $60, 000. Lifting costs were around $0.16 per barrel in 1919, though they were considerable less for wells in flush production. The first wildcatters in a field could make a considerable amount of money with limited capital if they received the market price (which varied between $1–2 per barrel during the 1920s). The trick was to finance additional wells with the revenue from the initial well, produce oil as fast as possible, sell out once the price dropped and use the proceeds to finance the search for another field. The large companies took advantage of the independents’ lack of risk aversion through two leasing strategies. In checkerboard leasing companies would purchase 10-year leases scattered in a checkerboard pattern over wide areas of prospective oil country. Spread plays were used by independents or promoters to finance test wells by selling leases surrounding the hole, allowing the large companies the opportunity to purchase protection leases in areas of special interest.2 The major companies let the independents take the risks and then moved in once oil was found.

The small producer was still prominent during this period in the US, though his role would steadily decline. In 1919 there were 9, 814 producers, with an average capitalization of $246, 737, and annual production of 35, 674 barrels. In the same year however, the 32 largest firms produced almost 60 percent of total output, of which 35 percent was produced by 15 integrated firms. Only a thousand firms in that year had revenues exceeding $100, 000, but they accounted for 96 percent of the value of the oil produced.3

The genesis of the companies which would dominate the industry was in the discovery of oil in Texas, which resulted in the emergence of Sun Oil, Texaco and Gulf Oil, and the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust. The Standard Oil Trust had been under constant attack in state courts since 1904 when the federal government filed a bill in equity in the US Circuit Court for the Eastern district of Missouri against the holding company, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. The defendants were charged with violations of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890. In November 1909, Standard was found guilty as charged and in 1911 the decision was upheld by the Supreme Court. The Court ordered Jersey Standard to transfer to stockholders a prorata share of stock in each subsidiary. Jersey Standard and California Standard were the only two subsidiary companies which were fully integrated from pipeline to marketing. During the 1920s and 1930s the remnants of the Standard Oil empire as well as the newly emergent oil companies scrambled to integrate either forward and backward. Integration was accomplished by investing in facilities and purchases of existing companies. Most of the companies purchased were in the second rank of firms in their sector of the industry.4

The emergence of new technologies for finding and refining oil was partially responsible for the growth of these newly integrated companies. The shallow, easily noticeable fields had been found and new discoveries would require systematic and deeper exploration. Drilling capability increased rapidly with wells drilled to previously inaccessible depths of 5, 000 to 10, 000 feet. The rotary drill provided means for controlling the higher pressures encountered with deep wells, increased drilling times, and improvements in sampling quality, furnishing reliable data for subsurface analysis. Introduction of geophysical techniques, gravimetric, seismic and magnetic, along with the acceptance of geological methods, reduced risk in exploration.5 The new techniques improved the competitive position of the major integrated firms since only a large company could afford the staff and equipment required to make use of these techniques. Coordinated use of aerial photography, surface data, core drilling, micropaleontology, and geophysical techniques required a large staff of professionals and competent managers. Exploration by small operators concentrated on stratigraphic traps difficult to detect with the new techniques or small fields and extensions. Table 1.1 illustrates this trend.

Table 1.1 Discovery of Major US Oil Fields

| Period | Independent Producers | Major Companies | ||

| # of fields | million bbls | # of fields | million bbls | |

| | ||||

| 1871–1900 | 9 | 4,086 | ||

| 1901–1910 | 17 | 4,898 | ||

| 1911–1920 | 17 | 4,082 | 16 | 6,276 |

| 1921–1925 | 9 | 3,258 | 9 | 2,348 |

| 1926–1930 | 21 | 8,980 | 30 | 6,694 |

| 1931–1935 | 10 | 2,791 | 17 | 3,765 |

| 1936–1940 | 10 | 1,820 | 33 | 9,137 |

| 1941–1945 | 3 | 516 | 19 | 3,279 |

SOURCE: Owen, Trek of the Oil Finders, p. 472

Control of International Oil

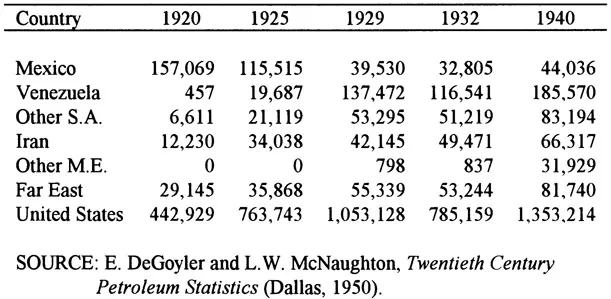

In the Middle East Anglo-Persian (British Petroleum) was becoming a major power in world oil due to its Persian oilfields while the Iraq Petroleum Company had commenced development by the end of the 1920s. In the Far East the Dutch East Indies were responsible for 75 percent of the region’s production. Control of world supplies was firmly in the hands of the International Majors, sometimes referred to as the “Seven Sisters” (the five American Majors plus BP and Shell) by the end of this period. Although Mexico had been open to all comers because of private ownership of mineral rights, its production peaked early in the 1920s (see Table 1.2). Mineral rights were obtainable in the rest of South America, but they were relatively expensive and the Majors were able to purchase the rights directly or indirectly from local actors. In the Middle East the mineral rights were owned by governments, allowing the Majors to obtain total control of exploration over vast regions. In the Far East and Africa colonial powers controlled access to potential oil lands, which gave a significant advantage to BP and Shell.

Competition for control of world oil became intertwined with national policy in the aftermath of World War I. The importance of petroleum for supplying fuel oil for the fleet, aviation fuel for the air force, and gasoline for motorized vehicles made access to crude oil a military necessity. While the British and French governments were well aware of their dependency on external supplies, the existence of large domestic supplies had caused the US government to be complacent with regard to supporting American oil companies in their attempts to gain access to foreign oilfields. The perception of shortages after the war resulted in a temporary change in the government’s attitude, persisting long enough to apply sufficient pressure to enable the American companies to enter the Middle East fields. The publication of the Edgar statement in May 1920, gloating over British control of world oil, combined with the Polk Report to the United States Senate, documenting the exclusion of American companies from various countries, motivated the Congress and the State Department into action. The State Department protested the exclusion of Standard Oil from the former Ottoman Empire and Dutch territories. Congress moved to bar foreign citizens from acquiring oil leases on public lands. Between the application of diplomatic pressure and the realization by Shell that it was risking large American investments for wildcat territory of uncertain value, entry of American companies into British and Dutch territory was accomplished.6

Table 1.2 Foreign Oil Production by Region (thousand barrels)

Seven American companies expressed interest in Mesopotamian oil, but due to the extended negotiations and financial pressures only three companies joined the Iraq Petroleum Company, Jersey and Socony each with 9.9 percent and Gulf with 3.96 percent of ownership. The “self-denying clause” prohibited any involvement in crude oil production in the Ottoman Empire by the owners of the IPC outside the auspices of the company. The final agreement of July 31, 1928, became known as the “Red Line” agreement because of a red line on a map delimiting the area of the self-denying clause.7

The Middle East was dominated by the Majors from the beginning. Major Frank Holmes, operating through the Eastern and General Syndicate, acquired an option on oil rights in Saudi Arabia in 1923, the Saudi-Kuwait Neutral Zone in 1924 and on Bahrein Island in 1925. The Syndicate sold their rights to Gulf in 1927, which, bound by the Red Line agreement which included Bahrein and Saudi Arabia, allowed Socal to take over the Bahrein commitments in 1928, and oil was found in May 1932. Bahrein Island had similar geo...

Table of contents

Citation styles for The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990

APA 6 Citation

Isser, S. (2016). The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990 (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1478345/the-economics-and-politics-of-the-united-states-oil-industry-19201990-profits-populism-and-petroleum-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

Isser, Steve. (2016) 2016. The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1478345/the-economics-and-politics-of-the-united-states-oil-industry-19201990-profits-populism-and-petroleum-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Isser, S. (2016) The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1478345/the-economics-and-politics-of-the-united-states-oil-industry-19201990-profits-populism-and-petroleum-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Isser, Steve. The Economics and Politics of the United States Oil Industry, 1920-1990. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2016. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.