- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Netherlands

About this book

One popular view of the Netherlands is that of a society oriented towards agriculture and associated processing industries. But although these activities enjoy greater prominence than in most developed countries, in reality the Dutch economy is based on a broad range of manufacturing, the extent and character of which has experienced rapid evolutio

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Historical and Geographical Background

AS AN EFFECTIVE functioning political entity, the Netherlands is not yet 150 years old. The opening of the nineteenth century found the country under French rule, and at this time only the present-day eastern boundary existed as a recognised frontier. Liberation was attained with the collapse of the Empire of Napoleon I, but the country remained linked with Belgium under the rule of Willem I who had succeeded to the throne in 1813. However, the Belgian link was effectively dissolved by the Belgian Revolution of 1830, and separation was officially recognised in 1839, the present southern boundary of the Netherlands then being established along a line almost exactly coincident with an earlier frontier of 1648. In the south-east, meanwhile, the years after 1795 saw a conglomeration of principalities and lordships become amalgamated into a province known as Limburg. Yet this process of amalgamation was protracted, and it was again not until 1839 that the new province was completely incorporated in the Netherlands. Thus, it was almost the middle of the nineteenth century before the country functioned as the national unit known today1.

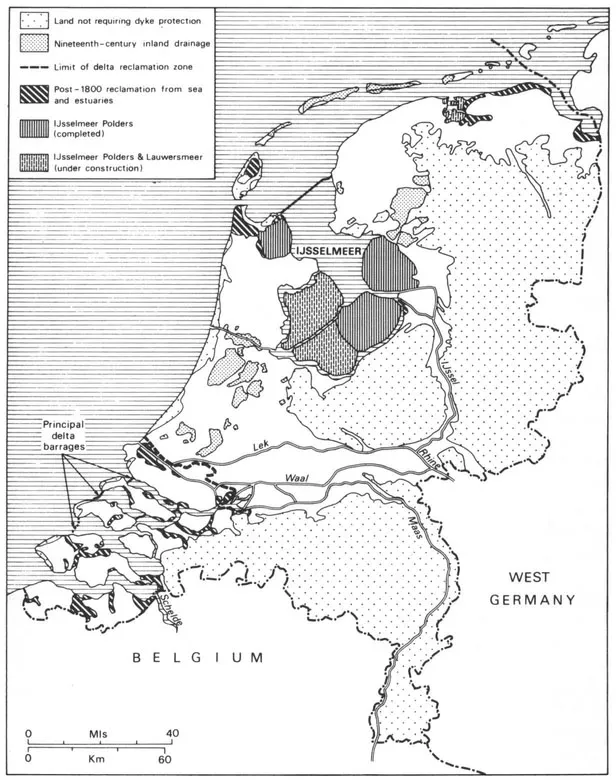

Although many areas lay at or below sea level, the territory covered by the newly emerged kingdom was not universally low-lying and subject to the danger of inundation (Fig. 1). Apart from western districts, many areas were covered by glacial material, mainly sands, gravels and, in the east and parts of the north, a veneer of boulder clay. These depositional features rarely rose above 30 metres, but over wide areas they were high enough to prevent the possibility of flooding by the sea or rivers. Consequently, the majority of the land endangered by floods was to be found in the west and south-west, where protection was

Fig 1. DRAINAGE AND SEA-DEFENCE SCHEMES SINCE 1800 SOURCE: Atlas van Nederland, VIII-4

afforded by a major belt of coastal dunes, together with extensive man-made dykes enclosing reclaimed land. In these districts, marine reclamation had progressed so far that little could be achieved by further work: in the complex delta of the rivers Rhine, Maas and Schelde, for example, only the narrow channels between islands were worthy of the effort and expense involved. As a result, during the nineteenth century the large majority of flooded land reclamation took place inland, particularly in the lake district formed by peat cutting between Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Extensive drainage work began here before 1800, but it was subsequently accelerated as drainage technology improved, and as the lakes (which tended to spread) became an increasing threat to towns and cities in the region. This phase of reclamation reached its zenith shortly after mid-century with the drainage of the Haarlemmermeer, a task only possible after the introduction of steam engines for pumping. Elsewhere in the country, however, little drainage was undertaken except in the lake region of Friesland, across the Zuiderzee. Here, too, flooded peat cuttings threatened local populations and agriculture, but the task of drainage was easier than in the west; it was undertaken, therefore, with less elaborate equipment, and with much less capital investment2.

These schemes, especially those of the west, demonstrated the ability of the Dutch to accept technological developments, to adapt them, and to apply them to their own requirements. Yet, despite this ability, and despite the early efforts of Willem I to build upon industrial reforms made in the French era, modernisation and expansion of the industrial economy remained painfully slow. To some extent this sluggishness was the result of a virtual absence of industrial raw materials within the country, but other factors also contributed. For example, a traditional reliance on waterways meant that little progress had been made towards the development of a comprehensive road network before the country achieved independence. Similarly, as late as the mid-1860s, almost no railways existed outside the western provinces. Thus many areas, some of them possessing infant industries and large labour reserves, remained relatively isolated. In addition to the isolation factor, however, national purchasing power remained low; the demand that did exist for many industrial products was easily satisfied by the import of manufactured goods, especially from Britain; and, particularly before 1850, internal economic growth was restricted by illiberal trade policies. As a result, it was not until the final quarter of the nineteenth century, following trade liberalisation and the growth and improvement of transport networks, that the Dutch industrial revolution began to accelerate3. Not surprisingly, therefore, at the turn of the century manufacturing had only recently become the principal source of national income.

In the twentieth century the Netherlands has been the scene of two major sea defence schemes and one major reclamation project (Fig. 1). The first defence works were planned early in the century when it became necessary to eliminate increasing threats of flooding around the shores of the Zuiderzee. Work on an enclosing dyke, 29 kilometres long, across the entrance to this sea began in 1923 and was completed nine years later. In this way, the Zuiderzee was transformed into a controlled-level fresh water lake, fed by Rhine water via the River IJssel, and known as the IJsselmeer. Out of part of this lake, three of the world-famous IJsselmeer Polders have already been reclaimed, while work is in progress on the remaining two. Originally conceived as a means of avoiding national food shortages such as those experienced in World War I, these polders continued to be viewed as largely agricultural investments until the late 1950s. Recently, however, the cost of reclamation relative to the return, together with increasing demands for residential and industrial space in western districts, have led to a fundamental reappraisal of the optimum rôle that can be played by this outstanding reclamation project4. Thus, although the majority of the reclaimed areas will remain, or be put to, agricultural use, the principal strategic function of the new land will be to alleviate urban-industrial pressures on the old mainland.

The other sea defence scheme is currently in progress in the Rhine-Maas-Schelde Delta. Begun in the late 1950s following severe floods in 1953, the Delta Scheme will eventually protect the deltaic islands from the effects of tides and storm surges by means of a series of barrages across the mouths of the estuaries. Almost no land reclamation is involved but, in addition to the greater security that will be enjoyed by the population, the investment will provide improved communications in the Delta and allow much closer integration with the remainder of the country. In this respect the end result is therefore likely to be similar to that in the IJsselmeer Polders, but the majority of the Delta will almost certainly be exploited for its recreational and agricultural potential, rather than for the large-scale diversion of population and employment from congested districts.

Provinces, Regions and Resources

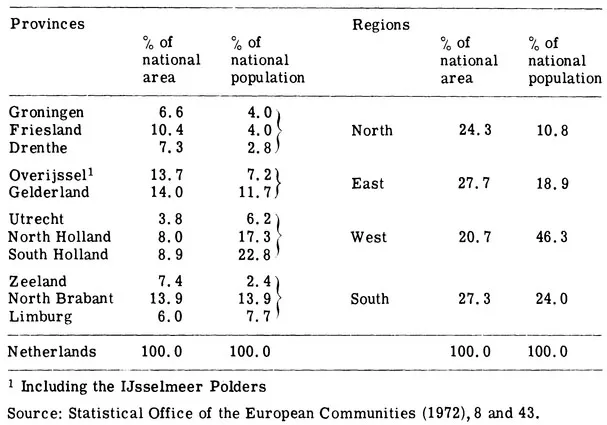

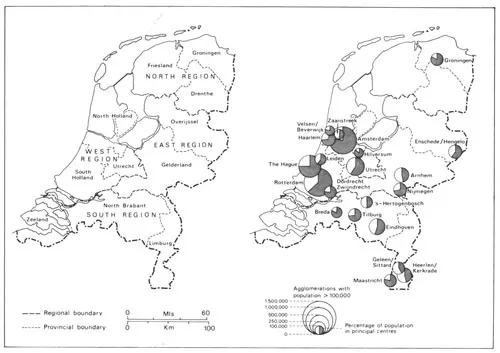

At present the country is divided into eleven provinces, although the completed IJsselmeer Polders will eventually be formed into a province in their own right (Fig. 2). A wide range of statistical data is published on the basis of this provincial framework, and the scheme is therefore referred to frequently in subsequent chapters. However, it is also common for data to be presented at two other levels. According to the first of these the country is divided into 129 Economic-Geographic Areas, data for which are particularly suitable for geographical studies of individual provinces. The second level is much more generalised, the data being presented according to a system of regions formed by the amalgamation of provinces. Occasionally this amalgamation is undesirable, for it can mask important contrasts within regions. But the use of the regional scheme is generally beneficial, mainly because its level of generalisation facilitates the identification of significant inter-regional differences. The regions and their provincial composition are listed in Table 1, which also provides details of their relative size. It should be noted that the position given to Zeeland in the regional scheme varies from source to source, some authorities preferring to place this province in the West, while others opt for its inclusion in the South5. Here, the latter solution has been adopted on the grounds that the province's historical isolation and distinctive economy separate it more clearly from the truly western provinces than from those of the South. It should be noted also that these regions are not operational units administered and planned by supra-provincial authorities. These functions continue to be performed at the provincial level, and although certain regional goals are recognised by the planning services and the Economic-Technological Institutes which exist in each province, there is little machinery designed to achieve co-ordination between authorities. We now turn to consideration of individual regions.

The West

The provinces of North Holland, South Holland and Utrecht form the West, the region corresponding most closely with the popular concept of 'Holland'. Here most of the land is below sea level and is protected in the west by the coastal dunes while, elsewhere, major dykes keep at bay waters from the IJsselmeer and the distributaries of the Rhine and Maas. Behind these natural and man-made ramparts lies the Rands tad, a discontinuous arc of towns, cities, industries and ports which form the economic heart of the Netherlands. A 'green heart' of relatively open country divides the Randstad into two 'wings', of which the more northerly begins in the province of Utrecht and curves north-westwards through the Utrecht Hills. These hills are a stretch of glacial outwash sands, pushed upwards by the bulldozing effect of readvances of the ice, and now in places heavily wooded. They are thus not-typical of western landscapes and, chiefly because of this, they are residentially highly desirable. In the province of North Holland, however, the hills die out and the complex of development around Amsterdam, Haarlem and the seaward end of the North Sea Canal spreads over low land more typical of the western Netherlands. The southern 'wing' begins at Leiden, runs to The Hague and from there turns south-eastwards through Delft and Rotterdam to the vicinity of Dordrecht. It is therefore completely contained by the province of South Holland, although in the south-east it comes close to encroaching on the territory of neighbouring North Brabant.

Table 1 PROVINCES AND REGIONS 1971

The Randstad is an example of intense urban and economic development yet, as is the case with the West as a whole, it has evolved from a base possessing virtually no natural resources. There are, it is true, clays suitable for brickworks, while the majority of the country's indigenous oil underlies South Holland6. But neither of these resources has ever maintained large-scale industrial activity, and the lead possessed by the West over other regions therefore stems directly from the exploitation of its only other natural asset, namely its location relative to the sea, major rivers and the manufacturing centres of the European hinterland. Long before the industrial revolution, this location fostered trade and, in its wake, the accumulation of wealth, population and industries. The impetus of growth failed in the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century, but it subsequently revived and has continued to the present day. Yet, during the present century, economic expansion has been distinct from that experienced earlier. In

Fig 2. PROVINCES, REGIONS AND AGGLOMERATIONS SOURCE: CBS Jaarcijfers (1972), 20-1

particular, industrial diversification has occurred as market- and labour-oriented activities have increased their significance. Also, there has been rapid development of the service sector: this has affected the region as a whole, but it has been especially important in the Randstad cities. However, growth of this nature cannot continue indefinitely in a restricted area without unfortunate consequences, and it has now led the cities to congestion point, so making urgent and effective regional planning vital. The current Randstad planning strategy involves the preservation of the region's green hear...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Historical and Geographical Background

- 2 The Developing Industrial Economy

- 3 Regional Variations in Selected Industries

- 4 Regional Policies

- 5 The Northern Randstad Wing

- 6 The Southern Randstad Wing and the Delta

- 7 North Brabant

- 8 Limburg

- 9 The East

- 10 The North

- 11 The European Dimension

- Notes and References

- Bibliography

- Appendix

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Netherlands by David Pinder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.