- 712 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hepatotoxicology

About this book

This book is destined to serve as a classic reference source to which researchers can turn for a historical perspective and basic information on the physiology, biochemistry, and pathology of the liver. Major areas covered in the book include histological organization, classification of chemical-induced injury, stages of cellular injury, and xenobiotic metabolism. Chapters discussing the use of biochemical methods to determine liver damage, the effects of various chemical agents of the liver, and hepatocarcinogenesis are also presented. Toxicologists, physiologists, physicians, biochemists, industrial hygienists, and others interested in the effects of chemical agents on the structure and function will find this book to be an indispensable source of information.

Information

Chapter

1

Structural Organization of the Liver

Katsumi Miyai

University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine Department of Pathology La Jolla, California

INTRODUCTION

The structural organization of the liver reflects its function that is to serve as a guardian situated between the digestive tract and the rest of the body. Because of this interposition, it receives large amounts of nutrients and noxious substances entering the body through the digestive tract and portal vein. Hence, a major hepatic function involves efficient uptake of amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids and vitamins and their subsequent storage, metabolic conversion, and release into the blood and bile. Biotransformation is another major hepatic function. This process converts hydrophobic substances into water-soluble products that can be excreted into the bile or urine. Although the biotransformation system is also present in other organs (e.g., kidney, small intestine, and endocrine organs), that of the liver is most important quantitatively.

Formation of bile requires the liver to have an exocrine gland structure. In addition, the liver also plays an important role in the body’s defense against macromolecules and particulate materials such as bacteria. Hepatic sinusoid-lining cells are quantitatively the most effective site of phagocytosis of particulate materials. Finally, the liver’s large vascular capacity serves as a reservoir in the regulation of blood volume and flow through the body (Jones and Schmucker, 1977; Jones and Spring-Mills, 1984; Miyai, 1979).

Therefore, the structure of the liver is adapted to meet the functional requirements and has the following characteristic features. (1) The liver has a dual blood supply (portal vein and hepatic artery), and the splanchnic blood from the portal vein undergoes a second interaction with cells in a microvascular system. (2) The organization of the hepatic parenchyma and the microvascular system is highly efficient for exchange between the blood and hepatocytes, that is, (a) hepatocytes usually form single-cell-thick plates so that they have at least two surfaces exposed to the blood, (b) sinusoid-lining cells are highly porous and, unlike ordinary capillaries, are not lined by a continuous basement membrane, and (3) the hepatocyte excretes its products into blood as well as bite. Morphologically, this is expressed as the separate compartmentalization of the cell surface of hepatocytes into vascular and biliary spaces.

The large cell mass of the liver is supported by two tracts of connective tissue, the portal tract and that surrounding the branches of the hepatic vein. The former encloses afferent blood vessels (portal and hepatic arteries), bile ducts, lymphatic vessels, and nerves, whereas the latter surrounds tributaries of the hepatic vein. The two connective tissue tracts interdigitate but do not connect with each other, being separated by the intervening parenchyma. The terminal branches of portal veins and hepatic arteries are connected with a highly porous microcirculation system (sinusoids) traversing the parenchyma. Portal tracts and tributaries of hepatic veins serve as important landmarks to understand the microstructure and function of the liver (Elias, 1949; Healy, 1970; Jones and Schmucker, 1977; Jones and Spring-Mills, 1984; Miyai, 1979; Rappaport, 1980).

CELLULAR COMPOSITION

The liver constitutes approximately 2–5% of body weight in the adult man (1400–1600 g) and 5% at birth. Hepatocytes, estimated to number 250 billion in normal adult human liver, comprise about 80% of the total cellular population (Table 1–1) (Gates et al., 1961) and 80% of hepatic tissue volume (Rohr et al., 1976). In the rat, hepatocytes constitute about 60% of the total cellular population (Table 1–2) (Daoust, 1958) and 80% of hepatic tissue volume (Table 1–3) (Blouin et al., 1977; Weibel et al., 1969). Cells lining the sinusoid in the rat are estimated to be about 30% of the total cellular population (Table 1–2) but comprise only 6.3% of tissue volume (Table 1–3) (Blouin et al., 1977). Other cell types constitute small proportions of the cellular population and tissue volume. Biochemical studies have shown that, in normal human liver, 4% of the total protein is collagenous (Seyer et al., 1977). Normal rat liver contains less collagen than does human liver, with only 0.55% of the total protein being collagenous (Seyer, 1980). Thus, despite its size, the liver normally contains relatively little connective tissue which provides an internal supporting framework for the parenchyma, and ensheathes blood and lymphatic vessels, bile ducts, and nerves.

Needle Biopsies (Germany) | ||

|---|---|---|

Cell Types | Apparent Distribution (% ± S.E.) | True Distribution (%) |

Parenchymal | 84.2 ± 2.7 | 86.0 |

Sinusoidal | 14.7 ± 2.2 | 14.0 |

Bile duct | 0.6 | |

Connective tissues | 0.2 | |

Blood vessel | 0.3 | |

Cell Types | Surgical Biopsies (Michigan)* Distribution (%) | |

Parenchymal | 79.8 | |

Sinusoid lining | 16.6 | |

Others | 3.6 | |

Binucleate parenchymal | 7.8 | |

*Figures are mean of four specimens.

Source: Modified from Gates et al. (1961).

BLOOD SUPPLY

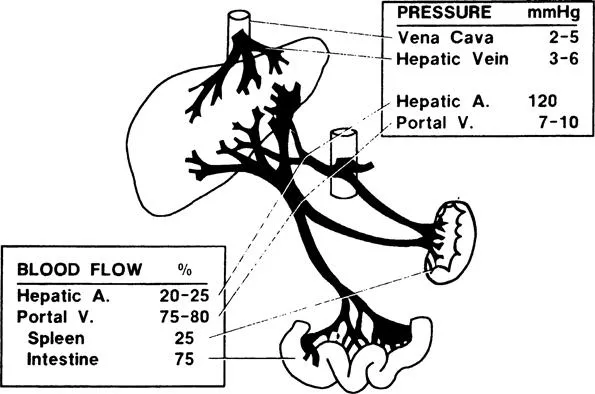

The liver receives blood through the portal vein and hepatic artery. The former accounts for 75–80% and the latter 20–25% of the total hepatic blood flow (1500 ml/min), which is about one-quarter of cardiac output (Figure 1). The portal vein conveys products of digestion to the liver after collecting the venous blood from the intestine. It also provides the liver with the venous return from the spleen. It is called a portal system because it conveys blood directly from one capillary bed (the intestine) to another (the liver) (Brauer, 1963; Healy, 1970).

Cell Types | Apparent Distribution (% ± S.E.) | True Distribution (% ± S.E.) |

|---|---|---|

Parenchymal | 68.8 | 60.6 |

Sinusoid | 26.4 | 33.4 |

Bile Duct | 1.7 | 2.0 |

Connective tissue | 1.7 | 2.2 |

Blood vessel walls | 1.4 | 1.8 |

Source: Modified from Daoust (1958).

Hepatocytes | 77.8 ± 1.15 |

Nuclei | 7.6 ± 0.50 |

Cytoplasm | 70.2 ±1.13 |

Sinusoidal cells | 6.3 ± 0.49 |

Endothelial cells | 2.8 ± 0.19 |

Nuclei | 0.44 ± 0.08 |

Cytoplasm | 2.36 ± 0.08 |

Kupffer cells | 2.1 ± 0.31 |

Nuclei | 0.39 ± 0.07 |

Cytoplasm | 1.71 ± 0.07 |

Fat-storing cells | 1.4 ± 0.19 |

Nuclei | 1.12 ± 0.04 |

Cytoplasm | 1.12 ± 0.04 |

Spaces | 15.9 ± 0.75 |

Disse space | 4.9 ± 0.35 |

Sinusoidal lumen | 10.6 ± 0.45 |

Bile canaliculi | 0.43 ± 0.05 |

*Data from Blouin (1977). Values are percentages % S.E.

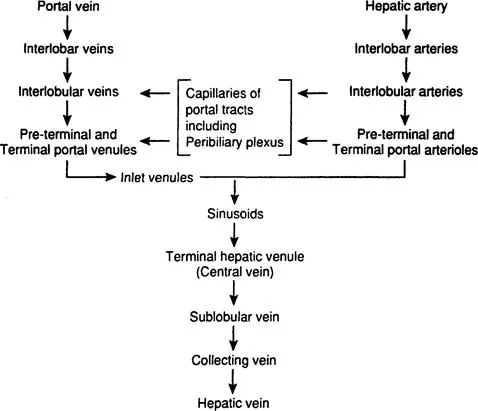

The portal vein enters the liver at the porta hepatis and divides into interlobar and subsequently into interlobular branches that run in the connective tissue of the portal tracts. There is no valve anywhere in the portal vein. Interlobular portal veins branch repeatedly into smaller terminal divisions that eventually become continuous with sinusoids. Preterminal portal branches lie in small triangular portal tracts. Terminal portal venules are seen in the smallest round or oval portal tracts and form the vascular axis for simple acinus (see Hepatic Acinus). Terminal portal venules connect with sinusoids by way of short perpendicular inlet vennules, which pierce through the limiting plate of hepatocytes and lead directly into sinusoids (Figure 2). These terminal segments lack a muscular coat (Burkel, 1970; Healy, 1970). In certain species, inlet venules may contain contractile endothelial cells, showing sphincter activity that regulates portal blood flow into the sinusoids (McCuskey, 1966; Rappaport, 1972, 1980). The sinusoids converge towards a terminal hepatic venule (central vein). As the terminal hepatic venules run through the parenchyma, they receive sinusoids from all sides (Burkel and Low, 1966). They unite with other hepatic venules to form a sublobular vein. The sublobular veins join to form one of the hepatic veins that empty into the inferior vena cava (Healy, 1970).

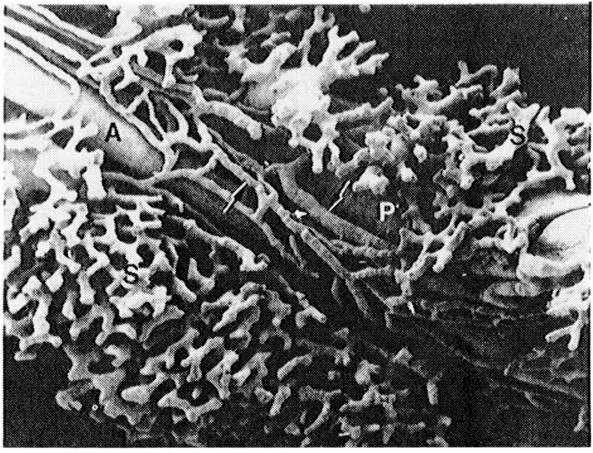

The hepatic artery accompanies the portal vein. One to five arteries of variable sizes may be seen within a portal tract, anastomosing with one another. In their terminal portions, hepatic arteries branch to form arterioles (50–100 μm in diameter) with the media consisting of a single layer of smooth muscle cells and precapillaries arising from the terminal arterioles in the larger portal tracts, which constitute a transitional vessel encircled at their origin by cuffs of smooth muscle, and capillaries (less than 10 μm in diameter) forming a network within the portal tract (Burkel, 1970). These terminal branches of the hepatic arterial system form (1) general plexus within the portal tract, (2) peribiliary plexus surrounding bile ducts, and (3) arterial capillaries emptying directly into the sinusoids (Rappaport, 1980) (Figure 3). The general plexus supplies the structure within the portal tract other than the bile ducts, sending terminal branches into sinusoids. The peribiliary plexus plays an important role in secretion, absorption, and concentration of bile (Rappaport and Schneiderman, 1976). Terminal branches forming this plexus pass into the sinusoids or join the terminal portal venules (Rappaport, 1980).

Some authors maintain that terminal hepatic arterioles and capillaries traverse the hepatic parenchyma to join sinusoids near the terminal hepatic venules (central vein) (Elias, 1949; Wakim and Mann, 1942). This concept has not been supported by observations by others who have not found such an anastomosis (McKuskey, 1966; Nakata and Kanbe, 1966; Rappaport, 1980). However, a recent study using scanning electron microscopy of corrosion casts has shown branches of intralobular arterioles terminating in the vicinity of the central veins, suggesting the presence of the aforementioned anastomosis (Kardon and Kessel, 1980). It seems that this controversy has not yet been settled.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 STRUCTURAL ORGANIZATION OF THE LIVER

- Chapter 2 A HISTOPATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF CHEMICAL-INDUCED INJURY OF THE LIVER

- Chapter 3 PATHOLOGY OF THE LIVER: FUNCTIONAL AND STRUCTURAL ALTERATIONS OF HEPATOCYTE ORGANELLES INDUCED BY CELL INJURY

- Chapter 4 XENOBIOTIC BIOTRANSFORMATION

- Chapter 5 LIVER FUNCTION TESTS IN THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF HEPATOTOXICITY

- Chapter 6 THE ISOLATED HEPATOCYTE AND ISOLATED PERFUSED LIVER AS MODELS FOR STUDYING DRUG- AND CHEMICAL-INDUCED HEPATOTOXICITY

- Chapter 7 BIOCHEMICAL METHODS OF STUDYING HEPATOTOXICITY

- Chapter 8 BIOCHEMICAL ASPECTS OF FATTY LIVER

- Chapter 9 FREE RADICAL DAMAGE AND LIPID PEROXIDATION

- Chapter 10 DRUG-INDUCED ABNORMALITIES OF LIVER HEME BIOSYNTHESIS

- Chapter 11 ALCOHOL-INDUCED HEPATOTOXICITY

- Chapter 12 MECHANISMS OF CHOLESTASIS

- Chapter 13 HEPATOTOXIC AND HEPATOCARCINOGENIC EFFECTS OF CHLORINATED ETHYLENES

- Chapter 14 ASSESSMENT OF HEPATOCARCINOGENESIS BY EARLY INDICATORS

- Chapter 15 TOXICOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF PEROXISOME PROLIFERATION

- Chapter 16 A POTENTIAL ROLE FOR IMMUNOLOGICAL MECHANISMS IN HALOTHANE HEPATOTOXICITY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hepatotoxicology by Robert G. Meeks,Steadman Harrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Toxicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.