1 Overview of Network Neutrality

In a 2017 article from Medium, Simon reflected on the historical and current truth behind network neutrality:

The fight over net neutrality is one of the most important political debates America is facing at the moment…And yet, there is one odd thing. Type “Net Neutrality” into your search bar and you will inevitably get a variation of one particular article as a result: The ‘Why you should care about net neutrality’-piece.’1

Simon’s reflection is correct; the internet is filled with thousands of articles that attempt to convince the public that network neutrality is a critical issue for 21st-century citizens. Beyond these cries for civic attention, the articles also suggest that there is a culture and history of citizen apprehension and ambivalence toward the regulatory topic. Although there are groups of involved and engaged citizens, the overall conclusion is that network neutrality, although important, is largely removed from public attention. Perhaps this backdrop illustrates the mandate to research and understand the moments of engagement throughout the network neutrality debate. Their perceived rarity (by journalists) encourages the examination of other forces, such as organizations, regulators, journalists and elected officials, in the network neutrality debate and how they shape contemporary policy. In addition, if there is a perception of a disengaged public, this suggests a need for scholarly attention to engagement, in the form of digital dialogic communication practices. Dialogue involves a desire for communication and adjustment from both participating parties. If one party is disengaged (or perceived as disengaged), then the ability to form a true dialogue may be challenged, as sociologist Eliasoph described the hesitation of public involvement in politics or policymaking.2

A large deterrent to public engagement rests on the perception that public policy is unapproachable and largely handed down from government elites. However, as Weible, Sabatier and McQueen argue, this perception of elitism is faulty, and in reality, most public policies are co-constructed by a number of actors invested in the process, including members of the public.3 Thus, public policy is a construction of the values of government, public, media and organizational interests.4 In many ways, construction and dialogue resemble each other: they both rely upon the involvement of multiple audiences, authentic listening and the mutual adjustment of policy goals.

Construction of public policy is important for a number of reasons. First, it allows all stakeholders to provide feedback and shape policies for favorable outcomes.5 This produces greater investment in policy decision-making and implementation.6 For example, in Canada, parliamentarians allowed citizens, organizations and media outlets to provide feedback on proposed trade policies in an effort to minimize backlash when policy was finalized. For parliamentarians, the construction process gave all parties a greater sense of investment, thus improving the quality and acceptance of the finalized policy.

Second, input from various stakeholders allows policymakers to generate informed decisions with greater evidence. For example, the Netherlands and Sweden invited scientists to contribute to policy task forces before drafting and proposing policy that would regulate these industries.7 Finally, policymakers also found a greater acceptance of policies from the wider public when stakeholder input is used in the creation process. Even in countries where policy is heavily controlled by state actors, such as China, the acceptance and ease of implementation of digital policies were greatly improved when policy was formed after discussion with stakeholders.8 Even when the co-construction is an illusion, policymakers who frame policy as a product of co-construction benefit.

The “co-construction of public policy” and “public policy development theories” originate from sociological work on social constructivism.9 Within this framework, policies are the product of many voices, interests and perspectives contributing to larger discursive trends and structures.10 Public policy is not a product of one political elite making decisions but rather a reflection of many stakeholders who impact the decision-making process. For example, a policymaker might meet with members of an impacted community, lobbying groups representing affiliated organizations, media analysts, political strategists and party/political leaders all before designing, proposing or implementing public policy. DeGrasse-Johnson identified this process when examining national dance policy in Jamaica, which produced greater acceptance of the policy once it was implemented.11

Policy constructionists argue that even when policymakers attempt to build policy in isolation without the input of various stakeholders, they still rely on information and ideas discursively constructed by these parties.12 It is impossible to escape the constructed world; thus, all policy decisions reflect some input from stakeholders. The degree of this input, and who gets the most voice in the process, is dynamic and changes based on the cultural and historical contexts of an issue.13 In four decades of network neutrality policy development and evolution, various stakeholders have dominated the construction process, arguably all but controlling policy decision-making at different points in time. This chapter examines the stakeholders responsible for the policy control of network neutrality over four time periods, reflecting on the digital dialogic strategies used by each group.

Co-construction involves a dialogue between parties as they attempt to make decisions and plan strategies. Elwood and Mitchell emphasize that dialogic relations must take place in policy development, particularly when there are many stakeholders involved in the process.14 Using Habermas’s theory of the public sphere, the authors argue that the internet is a new public sphere, allowing stakeholders to engage in “autonomous rational debate about the future.”15 In the new digital public sphere, dialogic communication allows the stakeholders to present arguments that will shape a policy such as network neutrality. These arguments become the foundations for policies as they are formalized through regulatory processes, such as lawmaking.

Kent and Taylor posit that organizations benefit from digital dialogic communication because it provides feedback from stakeholders on key policy and business issues.16 Similarly, governmental and regulatory officials benefit from digital dialogic communication because it provides information from the public on proposed legislation and strategic actions. While theories of digital dialogic communication have primarily focused on the relationship between an organization and its public audience, similar dialogic tendencies are observed in other parts of the policymaking process.

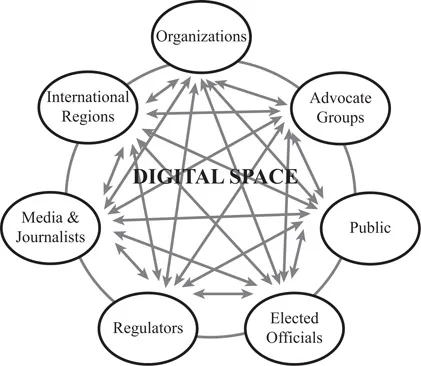

The key notion of digital dialogic communication builds from the public relations grand theory of “two-way communication” or using the internet to facilitate communication between an organization and the public. While there is some difference between dialogue and two-way communication (discussed later), this communication system appears in other places within the policymaking process, including between lobbyists and regulators/government officials, between journalists and organizations, and between countries. Two-way communication, facilitated through digital spaces, occurs between all stakeholders in the policy development process. As noted by Taylor and Kent, this communication can be a type of engagement with other stakeholders and the policy issue itself. Figure 1.1 illustrates how various stakeholders might engage each other to create policy.17

Figure 1.1 Diagram of dialogic stakeholders.

In this model, all stakeholders have the potential to engage each other, often using the digital space for this exchange. For example, the public engages in communication with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) through the online commenting system. Linklater argues that communication does not need to result in a direct reply to every online comment.18 Instead, a transformation of policy or perspective by the FCC (even the very slightest) demonstrates that dialogue occurs from digital dialogic practices. Digital dialogic communication is not just a conversation of words between an organization and an audience but part of a desire for the mutual adjustment of behavior, strategy or initiatives that includes perspectives shared during two-way communication.19 It involves listening to the other party and integrating feedback into decisions.20

There is ongoing criticism of the equation of dialogue with two-way communication (which this text aligns with).21 Dialogue requires two-way communication, but not all two-way communication is dialogue. Dialogue involves a genuine and ongoing attempt to integrate stakeholders into decision-making, while two-way communication, in public relations scholarship, requires communication to take place between stakeholders and the public.22 While this theoretical debate persists, evidence for two-way communication and dialogue as sometimes separate and sometimes overlapping systems appears throughout the network neutrality debate.

There is further ongoing debate of the value of dialogic communication and the “emancipatory potential” it provides for all stakeholders.23 Is all feedback equally valued in digital spaces? Is this a version of ethical universalism? While scholars continue to debate these questions, it is clear that the digital space provides a modern, yet complicated space for Habermas’s public sphere.24

So, who partakes in the construction process? Weilbe et al. argue that lobbying efforts by organizations traditionally hold the loudest voices in and most measurable impact on the policy development process.25 Historically, organizations paid large sums of money for lobbying firms to represent their interests to policymakers. Lobbyists have dominated the policymaking process because of their proximity to decision makers; the depth of resources at their disposal; and the success of their techniques, adapted from years of experience.26 As a result, lobbyists as extensions of organizations, are largely viewed as a dominant force in the policy development process, particularly on digital issues.27

However, a growing body of research suggests that digital technologies have greatly increased the ability of public stakeholders to participate in the policymaking process. Fung argues that digital spaces where the public can provide feedback to policymakers have improved the amount of public input in policymaking. For example, Congressional members’ use of Facebook and Twitter provides users with an opportunity to give feedback on proposed policies, answer questions, provide personal experiences and perspectives, and leave messages of dissent when opposing actions. While some scholars question the quality of this feedback and its contributions to policy development, most agree that social media and digital spaces provide unprecedented access to policymakers a...