eBook - ePub

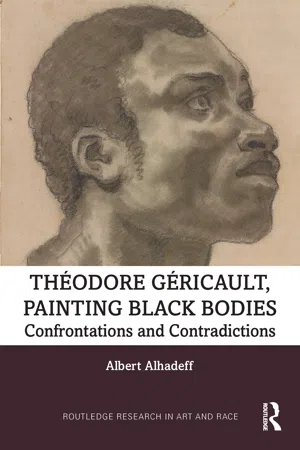

Theodore Gericault, Painting Black Bodies

Confrontations and Contradictions

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book examines Théodore Géricault's images of black men, women and children who suffered slavery's trans-Atlantic passage in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including his 1819 painting The Raft of the Medusa.

The book focuses on Géricault's depiction of black people, his approach towards slavery, and the voices that advanced or denigrated them. By turning to documents, essays and critiques, both before and after Waterloo (1815), and, most importantly, Géricault's own oeuvre, this study explores the fetters of slavery that Gericault challenged—alongside a growing number of abolitionists—overtly or covertly.

This book will be of interest to scholars in art history, race and ethnic studies and students of modernism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theodore Gericault, Painting Black Bodies by Albert Alhadeff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Black Bodies

An Ignoble Body, A Black Body

“... pas un trait d’héroisme et de grandeur ... rien d’honorable”1—“nothing memorable, heroic or honorable” in this canvas was the Gazette de France’s indignant dismissive response to Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (Plate 1).2 For the Gazette and the press in general, Géricault’s oil, a canvas of grand dimensions on view in the late summer of 1819 in the Louvre’s impressive Salon carée, was shorn of all redeeming and uplifting qualities. Depicted in a scene of men lost at sea on a makeshift raft, Géricault’s exhausted survivors, mired in hopelessness, lacked all moral fiber. Unable to transcend their plight, they deserved their fate.3 However, few if any of the Salon’s visitors studying the Raft observed that far from jettisoning art’s traditional tropes of heroism and honor, Géricault had vested them in a different guise, an unfamiliar face to Géricault’s cohorts and one they could neither discern nor accept. Indeed, if the Louvre’s visitors could not see the Raft’s challenge it was because its moral fiber was couched in a black body, one they deemed ignoble.

The black body they could not see was the signaling black, a dark-toned muscular figure set at the forward-most end of the raft (Plate 2). Capping a pyramidal rise of desperate figures clustered about his person, Géricault’s apical black waves a scrap of cloth before him hoping to attract a passing vessel that appears on the far horizon. With several of the raft’s survivors at his side echoing his stance, he faces the sea, perched precariously on an upright barrel, drawing attention to himself with his ragged bunting. Clearly visible to us, he was evidently invisible to the Gazette and to the other papers who reviewed the Raft—invisible, that is, in that he does not find a place in their accounts of the Salon,4 an omission that may have its roots in the waver’s color. Black, a slave or perhaps a former slave, surely an Other, he needs to be discounted.5 This in effect is the problem we face—namely, to understand the racial divide that distanced the races as whites enjoyed the fruits of their chatelled-slave labor. Indeed, the many visitors milling about the Raft were hardly aware of the system’s extreme brutalities to acknowledge them.6

With blacks reduced to chattel, it was all but impossible to assign a trait d’héroisme et de grandeur to a man of color. In the rare instance when Géricault’s “hailer” is cited, as in the Journal de Paris’ review, he is dismissed as “that man” (cet homme),7 a bland moniker insuring his anonymity. In effect, the Journal de Paris’ man could be any man on the Raft, he could be either “white” or “black.” But black he is! And that fact is fortuitously forgotten. Thus, by denying his color, that which indelibly isolates him from the other naufragés (shipwrecked survivors), his signal role is denied … a denial which in turn denies Géricault’s focus on blacks, a central tenet of his grand canvas.

Indeed for the Journal de Paris “the man’s” efforts will get him nowhere—“useless and exhausting,”8 is how the paper phrases it. As those who repudiated people of color never tired of saying, blacks can never amount to much. Surely, their endeavors are doomed to failure. Not only for the Journal but for Géricault’s peers in general, failure was synonymous with people of color. Thus, Géricault’s apical figure had to be demeaned, downgraded. Hear for instance the voice of one such critic—Antoine-Hilarion Kératry’s is speaking. The year is 1820:

Two or three sailors, worn out, climb atop a barrel, and held by other wretches, themselves fainting with weakness, strive to wave a few ragged cloths before them signaling their distress.

Deux ou trois matelots exténués de fatigue, montés sur une tonne, et qui soutenus par d‘autres malheureux, eux-mêmes défaillans, éssaient d’agiter, dans les airs, quelques lambeaux en signe de leur détresse.9

Deux ou trois matelots exténués de fatigue, montés sur une tonne, et qui soutenus par d‘autres malheureux, eux-mêmes défaillans, éssaient d’agiter, dans les airs, quelques lambeaux en signe de leur détresse.9

Hence Kératry’s pathetic image: Exhausted, expiring wretches massed about the Raft’s pinnacle. “[W]orn out,” sailors too weak to stand—a moving scenario, indeed, but it is not Géricault’s. Where Kératry focuses on exhaustion, Géricault focuses on elation; and where Kératry’s sailors barely stand, Géricault’s apical black surges forward, invigorated by hope, inscribed with life.

With Kératry replacing Géricault’s signaling figure with two or three sailors (deux ou trois matelots), one might suppose that Kératry saw what he saw because he could not entertain the thought that a canvas of such magnitude could be capped with a man of color—and just one man at that! Clearly, Kératry felt he had to down-play the latter’s importance—he had to lose him in a larger crowd, depict him (and the men gathered about him) as spent, drained of life. By emphasizing the hailer’s “weakness” Kératry undercuts his agency. Indeed, how can a man deemed hopeless lead a surge of hope—a question that for Kératry and for those who shared his racial biases was more than rhetorical.

Kératry’s sense that Africans were incapable and could not possibly take a leading role in any undertaking, not just in the Raft, needs to be underlined, for negrophobia was part of the temper of the day. A case in point is a text from 1819 and one contemporary with the Raft. A seemingly judiciously tempered tract on the Negroid race, it is in effect a thinly disguised biased surge of anti-black sentiment. Addressed to a professional audience of eminent medical practioners, and published in the Sociéte des médecins et de chirurgiens’s journal, its author, J. J. Virey (1775–1847), a doctor of note, bases his arguments—or rather, his racial theories—on a host of past and present scientific profiles by physiologists, anthropologists and other men of learning. Buttressed by numerous scholarly pronouncements and by impressive Latin sources, Virey launches into a long disquisition (it runs for more than fifty pages, one we will often return to in these pages) denigrating blacks, arguing that there “are two distinct and principal species that comprise humanity: the white species and the black species” (l’espèce blanche et l’espèce nègre)10—a clear division that demarcates the races, with the latter, as Virey goes on to argue, forever indulging in “the most dissolute excesses; his soul … wrapped up in gross animal appetites.”11 Hence Virey’s conclusion: with its “superior intelligence,”12 it is only natural that l’espèce blanche “govern all creatures.” And

as the God-head has willed that the weak and doltish submit to those more powerful … just as women submit to men, and youth to old age, likewise le nègre, less intelligent than whites, must bow down (doit se courber) and submit to his [the white man’s] presence—just as the ox or the horse, in spite of all their strength, heed man’s will; thus has it been proscribed by destiny.

si l’ordre éternel a voulu que les faibles, les incapables d’esprit se soumissent aux plus forts, aux plus intelligens … comme la femme à l’homme, le jeune au plus âgé; de même le nègre, moins intelligent que le blanc, doit se courber sous celui-ci, tout comme le boeuf ou le cheval, malgré leur force, deviennent les sujets de l’homme; ainsi la prescript une éternelle destineé.13

si l’ordre éternel a voulu que les faibles, les incapables d’esprit se soumissent aux plus forts, aux plus intelligens … comme la femme à l’homme, le jeune au plus âgé; de même le nègre, moins intelligent que le blanc, doit se courber sous celui-ci, tout comme le boeuf ou le cheval, malgré leur force, deviennent les sujets de l’homme; ainsi la prescript une éternelle destineé.13

Virey’s voice (just one learned voice among many spearheading an objective analysis of le nègre) was heard well into the nineteenth century14—and with it a damning view of black people, one that reverberated in response to Géricault’s Raft. Mid-nineteenth-century appraisals therefore did not just disparage Géricault’s signaling black, they were averse to his presence, to his race. Ernest Chesneau’s essay of 1861 on Géricault and the modern movement for the Revue européenne illustrates the problem. Abiding by tradition, Chesneau (1833–1890) reminds his readers that canvases of grand scale (pompiers) favor a centre moral, a moral center that holds the picture together. The Raft, says Chesneau, has such a unifying focus, a pivotal point: The centre moral de son [Géricault’s] tableau, c’est l’Argus15 (The moral center of his canvas is the Argus). But the Argus, the rescue vessel, is far away, a speck on the horizon. Barely visible, its presence is in doubt. Even the Raft’s naufragés questioned its presence. Given its elusive station, might not Chesneau’s central focus better fit a tangible body, a corporeal entity that caps the composition: Géricault’s impressive black? Still, in spite of his seeming indifference, Chesneau never denies the latter’s presence. Hence Chesneau:

There, a black (un nègre), held by his fellow castaways, has raised himself up on an empty barrel; he waves a ragged cloth against the ocean’s winds in a desperate attempt to signal the crew of the brick [l’Argus], whose hazy silhouette those among the least forsaken naufragés have discerned on the horizon.

Là, un nègre, soutenu par ses compagnons de détresse, s’est hissé sur un tonneau vide; il agite au vent de la mer un lambeau d’étoffe. C’est un signal désepéré adressé à l’équipage du brick, dont les moins défaits d’entre les naufragés ont distingué la grise silhouette à l’horizon.16

Là, un nègre, soutenu par ses compagnons de détresse, s’est hissé sur un tonneau vide; il agite au vent de la mer un lambeau d’étoffe. C’est un signal désepéré adressé à l’équipage du brick, dont les moins défaits d’entre les naufragés ont distingué la grise silhouette à l’horizon.16

True, although Chesneau concedes the hailer’s presence and his color—a concession that borders on confession—he will not give him pride of place, the Raft’s centre mo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Black Bodies

- 2 Prurient Bonds

- 3 Editing and Emendations

- 4 Parity

- 5 Fabricating Blacks

- 6 Deference and Decorum

- 7 Empathy

- 8 Quotidian Portraits

- 9 Epilogue

- Selected Bibliography

- Index