It is not easy to reconstruct in any detail the history of recording in social work. A few studies of actual records over varying periods of time have been made, but the object has usually been to trace general changes in methods of work and assumptions rather than to describe in detail changes in the form and style of recording. Thus, Clement Brown (1939) refers to her unpublished study of eighty records compiled between 1924 and 1934. She suggests that this indicates a shift in the social worker’s attention from certain kinds of behaviour (e.g. honesty, cleanliness) to personality and a greater emphasis on the account an individual himself gives of his life and situation. Alsager Maclver (1935) makes a brief comparison of the slim records of 1899 and the much stouter volumes of 1935. In the former, ‘the consideration and discussion of underlying motives is also absent and one feels that case-work has gained by making a study of these and an attempt to fathom them before deciding on a plan of help’. More recently an impressionistic study (Timms, 1961) of sixty-eight sets of case papers from the Charity Organisation Society covering the period 1887 to 1937 concluded that

for most of the period caseworkers work on a foundation of practical theorems; they expect reasonable behaviour and the maintenance of moral standards and they show faith in the plasticity of human nature. They collect information with varying degrees of care, judge it according to the views of the ordinary practical, moralising citizen and administer with varying degrees of warmth and success routine procedures which have the authority of time and the support of cumulative but unrefined tradition.

These and other studies show that old social work records help us to see broad changes in social work but they provide only indirect illumination of changes in the theory and practice of recording. A satisfactory history of recording—as of all other aspects of social work—is still needed, and in this section we have to rely almost exclusively upon secondary sources. These sources will be used in two ways: to indicate broadly what appear to be the main changes in recording practice and in attitudes towards ‘the record’, at least so far as the social worker is concerned; and to provide a comparison of the only three texts devoted to the subject of recording in social work (Sheffield, 1920; Bristol, 1936; Hamilton, 1946). These texts are, of course, American, but British work on this subject is extremely sparse and scattered. Between 1912 and 1947, for example, the Journal of the Charity Organisation Society refers hardly at all to the subject.

Some broad changes

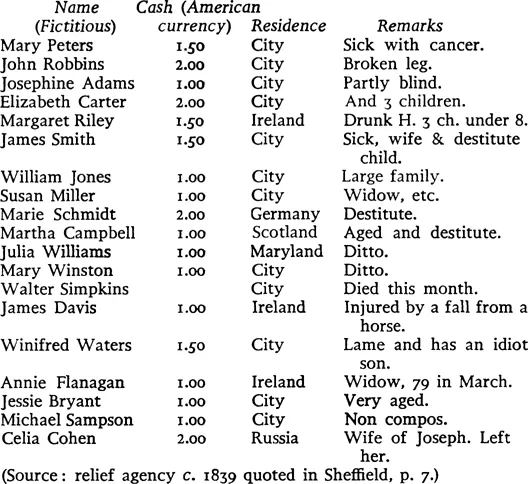

Recording in social work seems to have gone through four more or less clearly differentiated phases, though it would be difficult to associate any one phase with a defined period of time. The first phase is perhaps best characterized as that of the register-type record. In using single line entries to record the names of clients and the help given or not given, social agencies were beginning to keep records, but only just, as the following examples will indicate:

Entries of this kind must have been a feature of poor relief agencies for centuries.

The second phase of recording in social work probably began in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was characterized by more detail especially in relation to the client’s own statement of his or her problem, the verification of what were seen as certain key facts, and the recording in abbreviated diary form of business transacted with the clients or in connection with their affairs. An early study of case records noted that ‘early case-papers show that the office work and enquiries were all done by one person, a paid agent—brief and formal in his reports, much impressed with discovering the character of each applicant’ (Fifty Years Ago, 1926). The aim of the Charity Organisation Society to bring order and businesslike efficiency into the muddle of voluntary social work is very evident in the attention given to the records that the Council of the Society expected its district offices to keep. Books and Forms is the rather ominous title given to a Charity Organisation Paper first published in 1871. A Visiting Form was to be used to take down the statement of the applicant (this consisted of the applicant’s description of the problem together with some comment by the visitor; the following comment from a C.O.S. case of 1922 is atypical of a much earlier period only because of its disarming frankness: ‘Applicant is a youngish looking man and appeared respectable. I was not altogether taken with him, but this is only an impression not based on anything’). Each applicant was to be given a number to be entered in the Record Book. A Decision Book was to be used to record decisions, which later were also entered in red on the case record, Mowat (1961, p. 29) notes that besides the Visiting Form there were forms for subscribers, for reports to subscribers, for enquiries to schoolmasters and to employers.

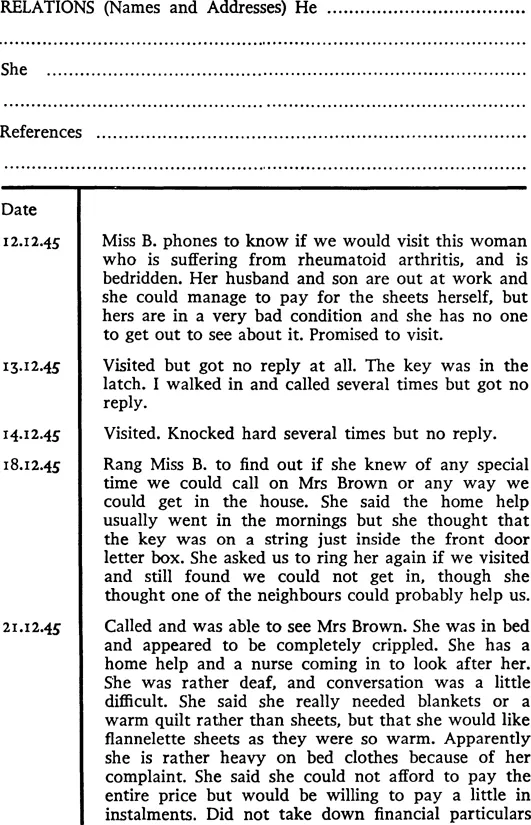

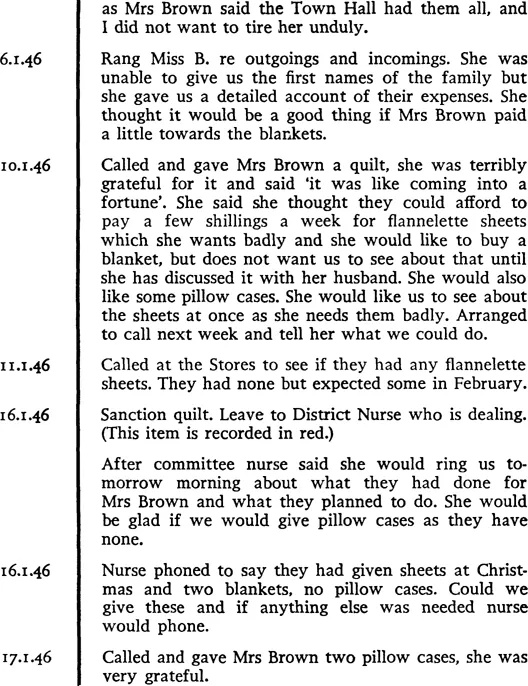

This phase—of great practical detail and of the diary-type entry—can be used to illustrate a tendency in social work recording which is not particularly confined to any one period of time, namely the description of what Sheffield has called ‘behold-me-busy details’. Some idea of the kinds of detailed records as well as the nature of a social work record in this phase can be obtained from the account on pp. 10 and 11 of an actual record taken from material collected for a study to which reference has already been made (Timms, 1961).

The case was originally referred in 1937, but the record is typical of those made in the C.O.S. in both earlier and later periods. The particular episode on which our attention will be focused concerns a further referral in December 1945 when a social worker asks the C.O.S. to help Mrs Brown with bedding. The front sheet is completed again as shown in Figure 1.

The third phase of social work recording concerns the process record. According to Hamilton this was in high favour in America in the second half of the 1930s, and it has for some time in Britain been accepted as playing an essential part in the professional education of the social worker, even though it has never been practical as a regular mode of recording day-to-day work. Its fairly widespread use owed something to psychoanalytic theory and something to the invention of the typewriter. A process record attempts to present an account of the interaction between social worker and client as this develops in the course of an interview. It differs from a verbatim record, which attempts to present a total recall of an interview, since the primary focus on the flow of the interaction entails considerable selection. The process record is often fairly lengthy since it involves reporting both sides of an interaction and the significant cues to which the worker, on the one hand, and the client, on the other, are responding. For an example of a process record see the Appendix, which contrasts three different forms of record (electric, process and summary) used for the same material.

The fourth phase of recording represents in one sense a compromise. Each phase offers some advantages, though the simple register would now be seen as the basis for some general statistical description of the agency’s caseload rather than a self-sufficient part of work with any particular client. The emphasis in the fourth phase is on differential recording. A narrative approach is usual but the liberal use of the summary makes the record more manageable. At the same time particular parts of the work can be recorded as process; for example, the first contact or any particular interview that appears particularly puzzling or fruitful. The flexible character of this phase of recording is well described by Hamilton (1946):

Applications or early interviews are often given in the client’s own words or in a selective process; later interviews, only when the interplay is subtle or unusually significant. Ability to make diagnostic and evaluation comments may provide an effective short-cut instead of full-length verbatim. A whole series of treatment interviews may be just as effectively summarised as the facts of social study. Interviews in which the emotional values are minimal, or when the anger or aggression or fears are obvious, or in which the case work relationship is not involved to any great extent, or when social resources are realistically utilised by self-directing clients, or when information is sought on a straight question-answer basis, all this and much else can be condensed, arranged and summarised ...

So far in this section I have tried to describe four phases of recording in social work. It is probably the case that examples of each phase could now be found co-existing at the same time in the same county and even in the same agency. Historical research does not help us to discern the beginnings and the ends of each phase. In so far as actual records have been studied they have been used to illustrate a type rather than prove an argument; it is, incidentally, precisely in this way that case illustrations are used in social work texts. Broadly speaking, however, the phases that have now been identified represent some important shifts in ideas about what constitutes a good record, even though existing studies are silent on the developments of recording in work other than social casework.

It is also important to attempt to view the development of recording within the context of changing attitudes to the practice of making records. These are obviously complex, but for purposes of illustration two aspects will be mentioned: changes in the social worker’s realization of the impact of investigation and changes in the value attached to recording.

The C.O.S. considered a proper investigation of a case to be of the utmost importance. The ‘facts’ of a case— and the range of significant facts appears extremely limited to modern eyes—had to be discovered to detect the undeserving and to form a possible plan of help. Ribton Turner, the first secretary of the COS. or, as it then was the Society for Organising Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicity, describes (in the Charity Organisation Reporter, 31 January 1872) an early instance of investigation after he had seen a man and woman outside his house singing.

The tune was ‘Home Sweet Home’, but he believed the words were those of a begging petition. He spoke to the girl... She said she was formerly at the York Tavern. He asked her if she was prepared to go into service again. She said ‘no’ ... He found from enquiries made that the girl had not been in the situation (at the York Tavern) for two or three years; but at the last situation she held she had been accused of theft.

In these early days of the C.O.S. the record was seen as a collection of evidence that would justify a decision and describe very briefly the way help was given. In this perspective the applicant was seen in the passive role of informant or as executor of the casework plan: only very limited aspects of his or her behaviour needed to be recorded. On the other hand, it seemed important that the applicant should know that his statements were being recorded. Mrs McCallum in a discussion of a paper prepared for the Council of the C.O.S. in 1895 (‘How to Take Down a Case’) firmly expressed the view that the case paper should not be kept out of the applicant’s sight; facts were going to be recorded and it was preferable that this should be done straightforwardly in front of the applicant. Slowly the emphasis on evidence weakened and questions of the professional relationship between client and social worker came to be considered paramount. This change of focus had a noticeable effect on attitudes to the case records. Its existence came to be experienced by the social worker as somewhat embarrassing. Thus, in 1947 a medical social worker stated that the interviewer ‘writes down nothing of intimate personal detail in his (the client’s) presence, she keeps record cards and case papers out of his sight and knowledge as much as possible’ (Snelling, 1947). Such a viewpoint raises some interesting questions concerning the client as a full participant in any helping process.

As the social work record became less valued as evidence a tendency developed to regard recording as a kind of incidental, mechanical extra. Such an attitude is not unknown at the present time, but it seems to be found first in the early years of this century. Case papers, according to one writer (Lawrance) in 1912 ‘are the mechanical side of case-work—not casework itself. At a slightly later date Attlee, when he was educating future social workers, recorded his opinion that ‘Visiting people in their own homes is a good experience ... a little general conversation before putting questions will assist in enabling the visitor to get some idea of the kind of person she is visiting ... The filling up of case-papers is merely a matter of accuracy’ (Attlee, 1920). Such a view of recording did not receive much support in the later literature which has, on the whole, repeated (rather than examined) Bristol’s view that ‘... case recording is, of course, an integral part of the case work itself. Hence, a separation of the latter from the former could not be effected even if it were desirable to do so’ (Bristol, 1936, p. viii). When later writers refer to ‘mechanics’ in recording they have in mind ‘bookkeeping’ details rather than the record as a whole (see Hamilton, 1946, p. 6).

Three texts

The three main works devoted to recording have already been mentioned. The comparison that follows in this section will be concerned with illuminating any changes in ideas on the practice and theory of recording in American social work in the period marked by the dates of first publication, i.e. 1920-46.

It is possible, of course, to compare these studies in many different ways. In terms of style, for example, neither Bristol nor Hamilton can match what to contemporary ears is the welcome stringency of Sheffield. ‘Is treatment’, she asks, ‘ordinarily furthered by the knowledge that a woman is short? Should we do something different if she was tall?’ In this section, however, attention will concentrate upon the different ways in which the authors discuss the purposes of recording and the obstacles in the way of the creation of good records.

For Sheffield the record is the social case history, and she begins by stating the crucial importance of clarity about the purpose for which such a history is compiled and kept.

The nature of a social case history is determined by the kinds of purpose it is intended to subserve. From its subject matter down to the thickness of the paper it is written on, from the facts to be selected as important to mechanical devices for convenience, all questions relating to it must be decided in this light. The first step, therefore, in a discussion of the case record is to make clear the use we expect to put this document to.

Each author attempts to meet this challenge by stating a number of reasons for recording and keeping case records. Sheffield identifies three ends to be achieved: ‘(1) the immediate purpose of furthering effective treatment of individual clients, (2) the ultimate purpose of general social betterment, and (3) the incidental purpose of establishing the case worker herself in critical thinking’ (pp. 5-6). Bristol divides the purposes of case records ‘into four main categories, namely, their use for (1) purposes of facilitating treatment, (2) study and research of social problems as a basis for social reform, (3) training of students, as well as for teaching purposes generally, and (4) educating the community as to its social needs and to the place of social case work in filling some of these needs’ (p. 5). Finally, Hamilton refers very generally to the work of Bristol and Sheffield, without attempting any cumulative assessment of their views or of any differences her own views might make to the received wisdom of the past. She acknowledges the part records might play in education and in research, but gives first importance to the fact that ‘The practitioner in any one of the humanitarian professions is obligated to improve his skill in the interest of his clients, and to make his profession as a whole increasingly effective in the public interest” (p. 3).

There is clearly no contradiction between the authors as they describe the purposes to be served by the case record, but there are differences in priority. In particular there seems to be a certain narrowing of purposes in Hamilton compared to the other two authors. This becomes more apparent if Sheffield’s third and ultimate purpose is given in a little more detail. She argues that ‘the purpose of social betterment should not be thought of as superseding this individual claim (i.e. the welfare of the client); rather should it illuminate the case problem by constantly relating the difficulties of one client to defects or maladjustments in the social order’ (p. 15). She then lists several ways in which this ulterior purpose may be served, including showing ‘the typical combinations of character traits or of circumstance and character which make for the various forms of dependency’ (p. 17). This recognition of the importance of establishing typicality (the ...