- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Space Stations: International Law And Policy

About this book

This book explores the international law and policy relating to space stations in terms of specific barriers to utilization and considers methods or policies designed to overcome perceived barriers. It deals with the institutional possibilities and alternatives for space station ownership.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Space Stations: International Law And Policy by Delbert D. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Space Stations

Over the past several decades the term "space stations" has developed a number of connotations. To the science fiction enthusiast or to those interested in promoting the habitation of outer space, the term implies a manned facility orbiting the earth. The design described for such a facility usually involves a relatively substantial population of men and women living and working in a simulated earthlike environment complete with artificially induced gravitational forces. This concept of a "space station" is the one popularly held in the United States and espoused in fiction and nonfiction literature.1

In Europe the term "space station" refers to any facility, manned or unmanned, that is larger than a conventional satellite and located in outer space. Even in the United States, different interpretations of the term are made by relevant government and aerospace industry officials. Manned experimental space facilities, such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Skylab and the Soviet Salyut-6, despite their relatively small size in comparison to the popular U.S. concept of a "space station," are referred to as such.2 In addition, numerous governmental and industry designs for unmanned, automated facilities stationed in earth orbit are referred to as "space stations."

Due to the existence of these different connotations it is useful to derive a working definition of the term "space station" in order to proceed with descriptions of the variety of these objects as well as an analysis of the law and policy relative to them. In this volume the term "space station" means a man-made object or facility in outer space established with a purpose, such as to provide goods or services. In addition, in this volume the term is applicable to a space facility that is larger than a conventional space satellite and that is intended to be stationed in outer space for a relatively long-term period of use. Such a facility may or may not provide for human habitation, and it is apparent that most space stations, in the near future, will be unmanned. Therefore, the term "space station" should not be restricted to any one type of outer-space facility, nor should it, in the context of this volume imply any specific connotation of design or habitability.

General concepts of international law and policy will apply to all types of space stations. Hence, a broad, generic definition of "space station" that includes all such facilities is not only appropriate but necessary as well for a comprehensive review of applicable law and policy. Particular legal and policy determinations relative to certain types or categories of space stations will subsequently be derived from these general law and policy concepts.

The Variety of Space Stations

An understanding of the concept of "large space structures" is a fundamental prerequisite to any review of the variety of space stations. This, in general, refers to facilities constructed in outer space from equipment and materials that are inserted into orbit. Conventional space satellites are launched into space as one completed unit, and, although particular satellites may have deployable antennas, solar panels, and other equipment that must be extended, they do not require actual construction in space. Thus, construction in space is one distinctive feature that characterizes "large space structures" and distinguishes them from conventional satellites or objects in space.

A second distinction is that such space structures are conceptualized as much larger pieces of equipment than conventional satellites. The magnitude of the structures may range from that of several scores of meters to several kilometers, depending on the design and intended utilization of the structure.

Most space stations will be "large space structures" in that they will be constructed in space, as opposed to inserted into orbit as one unit. These stations will also be larger than conventional satellites. However, some facilities that are known as space stations are not "large space structures." For example, Skylab was inserted into orbit as one unit rather than constructed in orbit. Thus, Skylab is not a "large space structure," even though it is a facility that is significantly larger and heavier than a conventional satellite and is considered by many as a "space station."

Utilization of space stations that are launched as single units will probably diminish in the future. This decrease will be caused through advances in space construction technology and the need for space facilities larger than those that can be launched as single complete units. Among the current plans, there is no space station contemplated that will not be constructed in space as a "large space structure," although some of the component parts of such stations may be launched into orbit as complete units and subsequently attached to the station.

The realization that space stations of the future will be "large space structures" has led many to consider these two terms as synonymous. Strictly speaking, however, they are not synonymous because the term "large space structure" refers to size of the facility and the mode of construction, whereas the term "space station" is an indication of the purpose of the facility. Even though there is a distinction between the terms, they are often used interchangeably.

The variety of space stations is limited only by the number of different practical uses, or applications that can be performed in outer space. Theoretically, space stations could each be designed to perform a single application, or mission, and thus there would be a different design or type of station for each application. In addition, there could be different designs for the performance of a single type of application. What may be more prevalent than single-purpose stations are multipurpose stations designed to perform a variety of missions, applications, and services.

When considering the potentially numerous types of space stations, it becomes helpful to classify and review them categorically. In this way the variety of space stations can be comprehended and discussion of relevant law and policy will be more meaningful. For purposes of this review, space stations have been classified into four areas: stations designed to obtain, process, and transmit information; stations designed to produce power; stations designed for specific applications, such as space science or materials processing; and large space stations, intended as population centers or colonies.

Space Information Stations

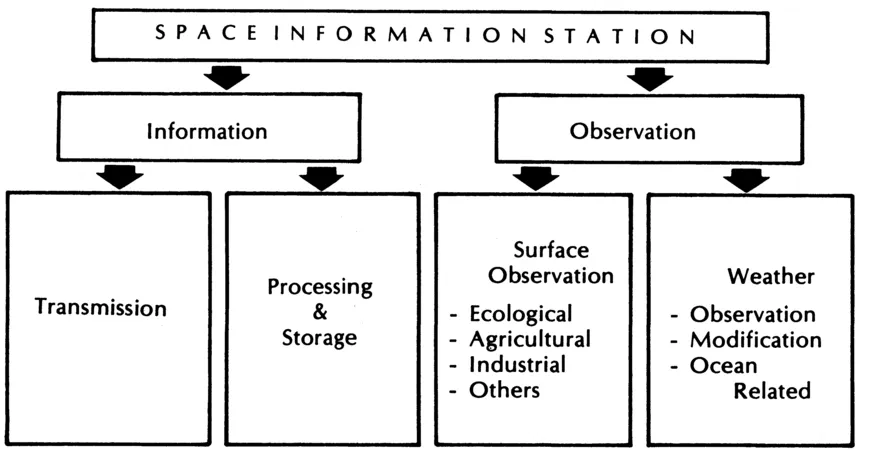

At present, the primary category of space applications involves the gathering, processing, transmission, and dissemination of information. Numerous earth satellites and systems are dedicated to the provision of these information services. Applications range from the relay of telecommunication signals for telephony, radio, television, and data to the collection and dissemination of earth, ocean, or meterological information observed or sensed from the remote synoptic vantage point of a satellite in space. Figure 1.1 illustrates application areas that could be performed on a space information station.

To understand the nature of a space information station it is necessary to know the basic attributes of conventional artificial space satellites and their orbits around the earth. As early as 1869, the notion that an artificial satellite could be used to transmit information was introduced in fiction literature by Boston clergyman, writer, and editor Edward Everett Hale in the "Brick Moon."3 Seventy-five years later, the idea that three artificial satellites, or "rocket stations," could provide worldwide communication coverage was presented by an electronics engineer and writer, Arthur C. Clarke.4 Clarke's proposition was that at an alti

FIGURE 1.1. Multiple applications possible on space information stations.

tude of 23,000 miles the rocket-station orbit could be made to coincide with the earth's rotation and thus remain stationary or fixed over one point on earth. Clarke's proposition is precisely the basis for the vast majority of space satellites that gather and transmit information.

The words "geostationary or "geosynchronous" are used to describe the types of earth orbit that Clarke earlier had postulated. A geostationary orbit occurs above the earth's equator, and a satellite placed in such orbit will remain fixed or stationary relative to any point on the earth's surface.

Microwaves, which are used in the transmission of signals to artificial space satellites, travel in straight lines or beams for relatively long distances. Hence, the microwave signals are aimed at the satellite in order to transmit to it. Thus, the geostationary orbit has proved ideal for communications satellites because it eliminates the need to track the satellite from the earth's surface when attempting to aim an antenna at the satellite to transmit or receive signals. In other words, since the satellite location is fixed in the sky, the ground-based antenna need only be aimed once to provide continued radio contact with the satellite.

However, not all information-related satellites utilize the geostationary orbit. At least one communications satellite system, the Molniya System developed by the USSR, utilizes an elliptical orbit around the earth at an angle to the plane of the equator, referred to as "inclination to the equator" of 62.5 degrees. This orbit is utilized so that, most of the time, the individual communications satellites remain in view of the far northern reaches of the USSR.5 Tracking earth stations that follow the movement of these satellites across the sky are necessary to remain in contact with them. In addition, periodic "hand-over" of comnication signals from one satellite to the next is necessary as each satellite is moved out of view of the ground stations.6 This system has been replaced by the Soviet Statsionar system, which utilizes the geosynchronous orbit, but it still serves as an example of a system that some observers think will be utilized in the future as the geosynchronous orbit is filled.

Other information-related satellites utilize orbits other than geostationary orbits. For example, NAVSTAR, a global system designed to provide extremely accurate instantaneous position, velocity, and time information for air, ground, and sea military units, is planned to utilize twenty-four satellites in three nongeostationary orbits.7 Seasat, an experimental ocean-sensing satellite designed by NASA, was designed for nongeostationary orbit due to the necessity for it to travel over the ocean regions of the world.8 In the area of meterological sensing, the National Environmental Satellite Service (NESS) employs a polar-orbiting satellite series, called TIROS-N, that is non-geostationary due to the necessity for meterological observation and sensing of the polar regions.9 These regions are difficult to view from NESS's geostationary series of satellites, called the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) series, located above the earth's equator.10

Although various types of orbits are used for information-related satellites, most plans for space information stations require placement of such structures in geostationary orbit. It would seem, therefore, that applications requiring orbits other than geostationary orbits could be without the benefit of space stations. Fortunately, this need not be the case, due to the capability for remote information-gathering.

Presently, certain information-gathering applications, performed by satellites in such areas as earth sensing and meteorological sensing, use sensors or monitoring devices that are not attached to the satellite itself. These remote devices, called remote data platforms, are positioned at locations where the monitoring is needed, and the information that is gathered is transmitted from these multiple points to one central point, the satellite, and subsequently relayed to a central processing facility.11 The remote-data-platform type of system, which naturally could be continued with geostationary space information stations, provides an analogy that clarifies the means by which applications requiring various types of orbits can be serviced by a geostationary space station. Satellites that operate in various orbits could become the remote appendages of central space information stations located in geostationary orbit.

Some plans, however, would require large space structures, which could be considered space stations, to be placed in nongeostationary orbits. For example, one design for an orbital microwave radiometer designed to perform combined earth, ocean, and meterological sensing would require an orbit of high inclination or, in other words, one that would cross the plane of the equator at a numerically high degree angle due to the need to view certain portions of the earth to obtain the desired information.12 Nevertheless, most of the space-information-station designs are for geostationary space stations.

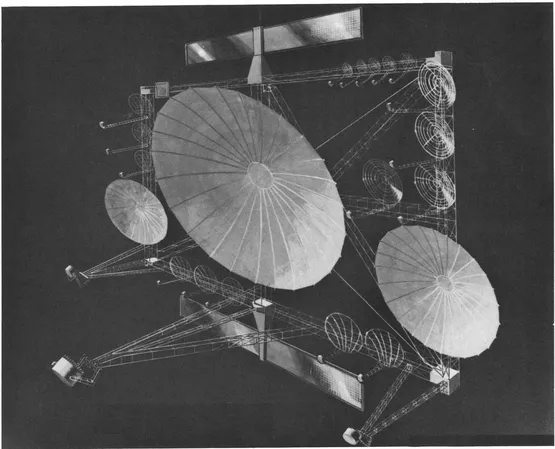

There are several plans, designs, and concepts for space information stations, including the following from the United States: the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's Geostationary Communications Platform;13 the COMSAT Laboratories' Orbital Antenna Farm (OAF);14 the Rockwell International's Electronic Mail Satellite;15 the General Dynamics Corporation's Convair Geo-Truss Antenna;16 the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Mobile Communications Satellite;17 the Grumman Aerospace Corporation's Public Service Platform;18 the NASA Langley Research Center's Soil Moisture Spacecraft;19...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Plates

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Space Stations

- 2 The Concept of Space Utilization via Space Stations

- 3 Institutional Alternatives for Space Stations

- 4 Applicable International Agreements

- 5 Legal Issues

- 6 The New Era in Space

- Appendixes

- Notes

- Index