- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Educational Leadership and Hannah Arendt

About this book

The relationship between education and democratic development has been a growing theme in debates focussed upon public education, but there has been little work that has directly related educational leadership to wider issues of freedom, politics and practice. Engaging with ELMA through the work of Hannah Arendt enables these issues of power to be

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Educational Leadership and Hannah Arendt by Helen M. Gunter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education Theory & Practice1

Introducing Hannah Arendt

Introduction

Hannah Arendt died of a heart attack on 4 December 1975. She was 69 years of age. She left an impressive intellectual legacy that continues to act as a provocation to think about current human predicaments in fresh and challenging ways. For example, her writings continue to speak to understandings of political protest (e.g. the Hungarian uprisings of 1956, Eastern Europe in 1989 and the Arab Spring from 2011), and so for Canovan (1998: vii) ‘Hannah Arendt is pre-eminently the theorist of beginnings. All her books are tales of the unexpected (whether concerned with the novel horrors of totalitarianism or the new dawn of revolution), and reflections on the human capacity to start something new pervade her thinking’. However, her political and historical analysis remains controversial: Miller (1995: unpaged) reports that in response to Eichmann in Jerusalem (Arendt 1963), ‘Walter Laqueur suggested that it was not so much what she had said, but how she said it: “the Holocaust is a subject that has to be confronted in a spirit of humility; whatever Mrs Arendt’s many virtues, humility was not one of them”.’

For Fraser (2004) ‘Hannah Arendt was the greatest theorist of mid-20th-century catastrophe,’ and she locates her as follows (2004: 253):

Writing in the aftermath of the Nazi holocaust, she taught us to conceptualize what was at stake in this darkest of historical moments. Seen through her eyes, the extermination camps represented the most radical negation of the quintessentially human capacity for spontaneity and the distinctively human condition of plurality. Thus, for Arendt they had a revelatory quality. By taking to the limit the project of rendering superfluous the human being as such, the Nazi regime crystallized in the sharpest and most extreme way humanity-threatening currents that characterized the epoch more broadly.

Having experienced totalitarianism, loss of freedom and statelessness as a refugee, Arendt’s political and historical analysis enables understandings of the relationship between thinking and practice. So a biographical ‘sketch’ as an opening to this book is less about a contextual vignette, or even a decorative start, and is more about how Arendt’s contribution to intellectual work is integral to a lived life. This therefore prompts myself as author and you as reader to consider how location within knowledge production is itself a political and historical issue, and how reading and engaging with Arendt’s life and work continues to resonate with ourselves nearly a century after her birth.

The aim of this book is to examine the politics of knowledge production through reading education policy and practice regarding ELMA using Arendt’s methods and ideas. In doing this I agree with Canovan (1995: 281) that ‘the most fruitful way of reading her political thought is, I believe, to treat her analysis of modernity as a context for the interesting things she has to say about the fact that politics goes on among plural persons with space between them’. The key questions to be addressed for the field of ELMA are to do with giving recognition to a plurality within field research, theory and professional practice: the type of knowledge that travels from one context to another, how particular ideas are accepted and used, the debates that take place, the existence and quality of theorising and the funding of research. In this opening chapter I intend to set the scene by introducing Hannah Arendt as a person, thinker and activist, and exploring how her approach to politics and history is useful for how the current challenges for the social sciences in general and public education in particular are debated.

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt was born in Hanover in 1906 into a well-educated left-wing home. She grew up strongly independent, relished intellectual work and she was a student of both Heidegger and Jaspers. After she married Günther Stern in 1929 she moved to Berlin, and following the Reichstag Fire she became increasingly involved in the resistance. After being arrested, inter rogated and released, she left Germany for Prague, then Geneva and finally Paris, where she met her second husband, Heinrich Blücher. They were interned as enemy aliens in France, and in 1941 they fled to the USA, where Arendt became a citizen in 1951. Consequently, there is a need to recognise, as Miller (1995: unpaged) does, that ‘Arendt’s life straddled two continents, bringing into contact two quite different intellectual cultures (and producing endless opportunities for misunderstanding)’. Scholars have provided accounts of Arendt’s life and work (see Baehr 2003, Bowring 2011, Young-Bruehl 1982, Watson 1992), so here I will draw out some important themes and messages that will both enable the reading of this book, and let us think about how Arendt’s life and work speaks to researching and conceptualising educational issues.

Education did not capture Arendt’s prime attention in regard to major writing projects but she did engage in a number of ways, not least as a school student:

Headstrong and independent, she displayed a precocious aptitude for the life of the mind. And while she might risk confrontation with a teacher who offended her with an inconsiderate remark – she was briefly expelled for leading a boycott of the teacher’s classes – from German Bildung (cultivation) there was to be no rebellion.

(Baehr 2003: viii)

During her expulsion she studied at the University of Berlin, taking classes in Greek, Latin and theology, and following the completion of school she studied at the universities of Marburg and Heidelberg (Bowring 2011). University provided her with an intellectual community and was a time when she was further politicised, not least through how she used her apartment in Berlin to hide political refugees. Just as she had faced the consequences of activism in school by being excluded, she experienced this as an adult, where she found herself variously detained and then released by the police in Berlin, transported to an internment camp in France, and then escaped to New York. This interplay between academic and political life is evident through her work as a journalist, author, editor, researcher and university teacher in Chicago and New York. Baehr (2003: vii) illuminates this by arguing that while she was a private person, she did confront issues in ways that generated controversy:

A Jew who in the 1930s and forties campaigned tirelessly on behalf of Zionism … Arendt opposed the formation of a unitary Israeli state. And how, given commonplace modes of thought, are we to cope with a theorist who documented the twentieth century’s fundamental rupture with tradition, while championing the notions of truth, facts, and common sense? Or with an author of one of the masterpieces of political ‘science’ – The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) – who expressed the strongest reservations about social science in general?

This is also evident in her writing on education, where she confronts bigger issues of the politics and history of the republic: so she articulated a Crisis in Education (Arendt 2006a) through a concern with the decline in authority; and in 1957 she wrote Reflections on Little Rock (Arendt 2003) in which she opposed the ruling by the Supreme Court on school desegregation because of the implications for the positioning of children in the political process.

So Arendt’s work is political and historical (Calhoun and McGowan 1997), with claims that she is a philosopher (Watson 1992), but she was an espoused political scientist (Kohn 1994): ‘she saw her work as directed to political decision making in the present: here, “between past and future,” all of us should be deciding how to act and how to live’ (Barta 2007: 88), and interestingly she described herself as ‘something between a historian and a publicist’ (quoted in Benhabib 2000: ix). Young-Bruehl (1982) entitles her biography For Love of the World as a means of illuminating Arendt’s ‘concerns for the world’ (1982: x), and Canovan (1995: 276) emphasises the message that people should be politically responsible in their lives: it is ‘our duty to be citizens, looking after the world and taking responsibility for what is done in our name’; she goes on to argue that if Arendt:

was a harsh critic of political irresponsibility under the conditions of pre-war Germany, it is not surprising that she had even less patience with American citizens who enjoyed the blessing of a free constitution, but who were too immersed in their private consumption to notice what use was being made of their power.

(Canovan 1995: 276)

In claiming that freedom is located in the spaces between people where political issues can be worked through, and in modelling such freedom through the debates she generated and participated in, then Arendt resisted categorisation. She has been labelled as both liberal and conservative. It seems that, as Baehr (2003: vii) identifies, Arendt ‘was a deeply paradoxical figure’, not least that ‘she was among the greatest women political thinkers of the twentieth century, yet one strikingly at odds with academic feminism’ (pvii). Her work has stimulated productive thinking and debate in education (Gordon 2001a) and genocide studies (Stone 2011), but at the same time silences (King 2011) and contradictions (Butler and Spivak 2010) have been identified in such a way that Baum et al. (2011: 7) note that Arendt was ‘viewed as a figure very much of her own time’. However, the renaissance in her work is explained by scholars because of her contribution to a range of debates about the condition of political life (Benhabib 2000), and Baum et al. (2011: 8) conclude that: ‘there are ways in which Arendt’s thought has been rehabilitated by the left in the service of a critique of the contemporary neoliberal state and its totalitarian tendencies’. This book is located in this critical tradition, as I intend to relate the growth and trends in knowledge production within ELMA to wider issues of politics and governance.

Reading and thinking with Hannah Arendt

Giving due respect to the focus on politics and the controversies that her work generated, and finding a way through her writings in order to appropriately engage with the ideas and context, is a key task of my role as an author. Following Canovan’s (1995) example I will not attempt to systemise her thinking by constructing and imposing a rationale that Arendt did not herself create. Instead I will ‘try to follow the windings and trace the interconnections of her thinking’ (Canovan 1995: 12) as a means of engaging with her ideas and methods.

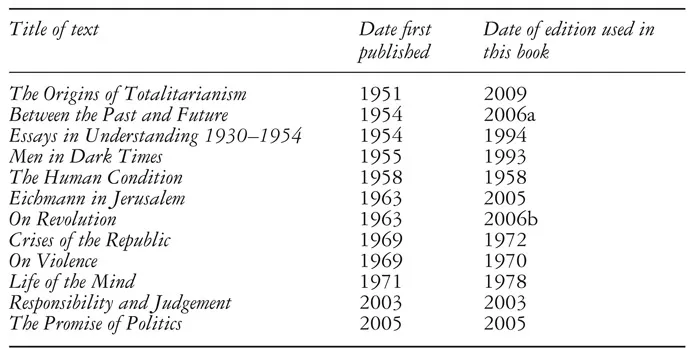

Arendt produced a body of work that is both conceptual and realistic, and can be variously and simultaneously descriptive, critical and experimental. She wrote major texts and published collections of essays, the bulk in her lifetime, but much was published posthumously, and this book will draw on a range of these works, as illustrated in Table 1.

Such a listing presents an impressive body of work but without engaged reading it is sterile, mainly because Arendt speaks to and about major issues pertinent to the social sciences. A challenge is where to start. Some writers begin with The Human Condition (Arendt 1958) and ‘this view argues that Hannah Arendt is a political philosopher of nostalgia, an anti-modernist lover of the Greek polis’ (Benhabib 2000: xxxix). However, Benhabib (2000), Young-Bruehl (2006) and Canovan (1995) all argue that

Table 1.1 Hannah Arendt’s key works used in this book

the starting point is The Origins of Totalitarianism (Arendt 2009), because ‘responses to the most dramatic events of her time lie at the very centre of Arendt’s thought’ (Canovan 1995: 7).

So in illuminating her work I will follow this approach, and re-emphasise how she worked on action and the plurality of political life. For Arendt action is political and public. Politics is space and needs space, it is where the person describes the self, where discussion happens and where the possibilities of ‘natality’ (Arendt 1958) can be realised. People are helped in this process by institutions as a legitimising, durable and stabilising framework through which the initiative and accommodation of the plural person can happen. What is needed to hold the common together are places where people can be separate but at the same time connected, like sitting at a table. When those spaces are removed, and people are essentialised into a type, then totalitarianism can be experienced. The Origins of Totalitarianism afforded Arendt the opportunity to analyse this, and while she recognised that such a regime could be defeated from external forces such as the use of military action to end the Third Reich, she struggled with the possibility that internal conditions could enable change. While she showed optimism about human capacity to do the unpredictable, it was change within the Soviet Union following the death of Stalin that led her to argue that regimes can be internally transformed. Of interest to issues discussed in this book is to develop understandings of ELMA in relation to the conditions that produce education policy, particularly about whether and how educational professionals do something new as action.

A second example comes from her attendance at and subsequent reporting of the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem (Arendt 1963), where as a journalist she sought to understand the processes that had enabled totalitarian tendencies to become a reality. Notably she argued that his actions were not based on an ideology as such but on a ‘deficit of thought’ or what she labelled his ‘banality’. Arendt gave attention to Eichmann’s careerism, and how he justified his actions on the basis of following orders. Of interest to issues discussed in this book is to develop understandings of ELMA in relation to those who practise it, and how engagement with reforms that do damage to education and children could be characterised as following orders.

In a third example, The Human Condition (Arendt 1958), she distinguishes between and examines labour, work and action. Labour is necessary to produce what a human needs to survive; work produces goods that are more durable and hence stabilise the social. Humans produce, and their products can outlast the processes that produced them and the objective for which they were produced. Humans therefore live amongst and with each other, and action with others requires the presentation and understanding of who the person is. Of interest to issues discussed in this book is to develop understandings of ELMA as labour, work and action, and I intend to examine Arendt’s (1958) contention that labour has come to dominate.

These brief encounters with just three texts show that Arendt engaged with the individual and the polity. While her writings specifically focus on Nazism, Stalinism, the Holocaust and nuclear weapons, she thought about the bigger issues of the human condition through examining the central issues of her time, and she kept on thinking about and refining her use of language and perspectives on events. It seems that she liked to watch the news and often shouted at the TV, and this is a helpful motif for understanding her approach:

it is tempting to say that she brought philosophy to bear on events; but the truth appears to have been more nearly the opposite. It was events that set her mind in motion, and philosophy that had to adjust … her thinking seems to ‘crystallize’ (the word is hers) around events, like a coral reef branching outward, one thought leading to another. The result is an independent body of coherent but never systematically ordered reflection that, while seeming to grow from within over her lifetime, according to laws and principles peculiar to itself, at the same time manages to continually illuminate contemporary affairs.

(Schell 2006: xii)

Methodologically Arendt was interested in how ideas and writing could generate understandings that could be debated in the polity; she wrote about the plurality of people and ideas, and operated on the basis that this was worth taking action for:

What is important for me is to understand. For me, writing is a matter of seeking this understanding, part of the process of understanding … what is important for me is the thought process itself. As long as I have succeeded in thinking something through, I am personally quite satisfied. If I then succeed in expressing my thought processes adequately in writing, that satisfies me also.

(Arendt 1994: 3)

Three main methods of generating understanding have been identified: first, she examined the meaning of words and the conditions to which they were applied, and so in The Human Condition she makes a distinction between labour, work and action: ‘Arendt wanted thoughts and words adequate to the new world and able to dissolve clichés, reject t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introducing Hannah Arendt

- 2 Hannah Arendt and the study and practice of ELMA

- 3 Using Arendt to think about ELMA: Politics and totalitarianism

- 4 Using Arendt to think about ELMA: The vita activa

- 5 Using Arendt to think about ELMA: The vita contemplativa

- 6 Thinking with and against Arendt

- Annotated bibliography

- References

- Index