eBook - ePub

Social Justice In A Diverse Society

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Justice In A Diverse Society

About this book

Issues of social justice have been an important part of social psychology since the explosion of psychological research that occurred during and after World War II. At that time, psychologists began to move away from earlier theories that paid little attention to people's subjective understanding of the world. As increasing attention was paid to people's thoughts about their social experiences, it was discovered that people are strongly affected by their assessments of what is just or fair in their dealings with others. This recognition has led to a broad range of studies exploring what people mean by justice and how it influences their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Justice In A Diverse Society by Tom Tyler,Robert J Boeckmann,Heather J Smith,Yuen J Huo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Social Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Introduction

Issues of social justice have been an important part of social psychology since the explosion of psychological research that occurred during and after World War II. At that time, psychologists began to move away from earlier theories that paid little attention to people's subjective understanding of the world. As increasing attention was paid to people's thoughts about their social experiences, it was discovered that people are strongly affected by their assessments of what is just or fair in their dealings with others. This recognition has led to a broad range of studies exploring what people mean by justice and how it influences their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

1

The Psychology of Social Justice

Justice as a Philosophical or Theological Concern

Throughout history, the writings of philosophers, theologians, and social theorists as diverse as Aristotle, Kant, Marx, Plato, and Rawls have been shaped by efforts to define how individuals, groups, and societies should or ought to behave. Although diverse in many respects, all of these efforts have in common the argument that both people and societies should be governed by standards of conduct beyond simple deference to the possession of power and resources. The use of terms such as "right and wrong," "ethical and unethical," "moral and immoral," and "just and unjust" connotes that conduct ought to be influenced by justice criteria derived from logical analysis; the works of religious, political, or legal authorities; and many other sources. In other words, there is a widely shared belief that societies ought to be constructed in ways that reflect what is just, and social theorists have devoted considerable energy to defining what is just in objective terms.

Consider the work of Rawls (1971) on moral philosophy. Rawls argues that justice is the first virtue of social institutions. In other words, in designing social institutions, it is important that criteria of fairness be considered. Rawls suggests several such criteria. For example, he argues that principles of justice suggest that social allocation rules should not injure those within a society who are the most disadvantaged. This is an example of an objective normative principle. Rawls does not argue that everyone will necessarily agree with this principle, but he does suggest that it is the just or fair principle to use on philosophical grounds.

Another example of an objective normative statement of justice is the pastoral letter of the United States Catholic Bishops (1986) entitled "Economic Justice for All." This letter speaks to issues of social obligation in economic settings from the perspective of a "long tradition of thought and action on the moral dimensions of economic activity" (p. 410). For example, the bishops argue that "Every economic decision and institution must be judged in light of whether it protects or undermines the dignity of the human person" (p. 411). Why? Because, they say, human dignity develops from people's connection with God and should be served by economic institutions and practices. Again, these arguments depend on having an independent perspective—in this case, religious writing—from which to view social rules and institutions. Throughout history, religious authority has provided an important alternative perspective on social justice to the rules and norms articulated by political, legal, and managerial authorities (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989).

Justice as a Subjective Issue

Justice is not just a set of principles derived from objective sources, such as religious authorities. It is also an idea that exists within the minds of all individuals. This subjective sense of what is right or wrong is the focus of the psychology of justice. Unlike the objective principles of justice discussed earlier, subjective feelings about justice or injustice are not necessarily justified by reference to particular standards of authority. Our concern in exploring subjective justice is with understanding what people think is right and wrong, just or unjust, fair or unfair and with understanding how such judgments are justified by the people who hold them.

The primary argument made in this book is that it is important to pay attention to people's subjective judgments about what is just or fair. One reason is that justice matters to people within social groups. People's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors have been widely shown to be influenced by their judgments about the justice or injustice of their experiences. Hence, people's feelings about justice are an important basis of their reactions to others. This assumption has led social scientists to try to understand how people decide that justice has or has not occurred.

Because justice is important to individuals in organized groups, the deliberations and actions of social actors—that is, both leaders and followers in political, legal, religious, and business settings—are also shaped at least in part by the belief that moral ideals of rights and entitlements are distinct from the mere struggle for possession of power or resources. In other words, justice is not merely a concern of philosophers and social theorists. It is an important issue in interactions among people. Authorities in all types of societies and groups shape their actions to fit their judgments about what people will feel is just.

The United States Catholic Bishops' (1986) statement can be contrasted to a statement made at approximately the same time by the White House Office of Policy Information (H. C. Gordon & Keyes, 1983). This statement addresses the same subject addressed by the bishops—economic policy. And it invokes the same issues of justice and fairness. In fact, the report is entitled Fairness II: An Executive Briefing Book. In contrast to the bishops' statement, however, the White House statement is political in character. It attempts to tap into people's values about justice without presenting some objective philosophical or religious criteria for defining justice issues and concerns. The report assumes that how people react to proposed changes in aid to families, food stamps, and job training will depend upon their views about fairness.

Consider the specific example of proposed changes in programs for the poor (H. C. Gordon & Keyes, 1983, pp. 24-25). The policy book asks, "Why is it fair to make any cuts in programs for the poor?" (p. 24). Three reasons are given for why such cuts are fair: (1) many programs for the needy give money to people who are not needy; (2) the cuts will primarily deny benefits to those who do not deserve those benefits; and (3) the program changes influence inefficiencies and errors, not basic benefits. Further, the report asks, "What is fair about inflation" (p. 25) that hurts the disadvantaged? In other words, the report assumes that when people consider proposed changes, they will wonder if those changes are fair. It is based upon the assumption that people care about what is fair.

Understanding people's subjective judgments about fairness is different from determining objective standards of justice—either by reference to universal moral principles, as Rawls (1971) suggests, or by reference to people's relationship to God, as the United States Catholic Bishops (1986) suggest. The psychological study of social justice involves efforts at understanding the causes and consequences of subjective justice judgments.

The study of subjective justice also can be illustrated by efforts to examine how people feel about the philosophical principles of justice articulated by Rawls (1971). For example, political scientists have examined whether people actually feel that principles of justice, such as those articulated by Rawls, are fair or unfair (Frohlich & Oppenheimer, 1990). They do so by having people participate in groups that are governed by varying types of justice rules. The people who are in such groups are then given the opportunity to evaluate the rules they experience. Their evaluations usually reflect their subjective assessments of the justice of these rules—that is, what they think is fair or unfair.

Efforts to explore what people think is fair address a variety of questions that arise in studies of people's thoughts and behaviors in social settings. Why, for example, do people view unequal treatment as being fair in some cases and not in others? Why do people accept decisions they view as fair even if those decisions are costly or create disadvantages? How do people react to collective injustice? These questions cannot be answered using a single objective definition of justice. Instead, they require a psychological approach to justice.

What Is the Psychology of Social Justice About?

Social psychologists have long been interested in the bases of people's cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors in social interactions. Why does a concern about people's feelings and actions in social settings lead social psychologists to study social justice? They study it because people's feelings about what is just or unjust are found to have important social consequences.

Studies show that judgments about what is just, fair, or deserved (or about what one is entitled to receive) are at the heart of people's feelings, attitudes, and behaviors in their interactions with others. Perceptions of injustice are closely related to feelings of anger (Montada, 1994; P. Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, & O'Connor, 1987) and envy (R. E. Smith, Parrott, Ozer & Moniz, 1994), to psychological depression (Hafer & Olson, 1993; I. Walker & Mann, 1987), to moral outrage (Montada, 1994), and to self-esteem (Koper, Van Knippenberg, Bouhuijs, Vermunt, & Wilke, 1993), Furthermore, judgments of fairness are related significantly to people's interpersonal perceptions (Lerner, 1981), political attitudes (Tyler, 1990; Tyler, Rasinski, & McGraw, 1985), and prejudice toward disadvantaged groups (Lipkus & Siegler, 1993; Pettigrew & Meertons, 1993).

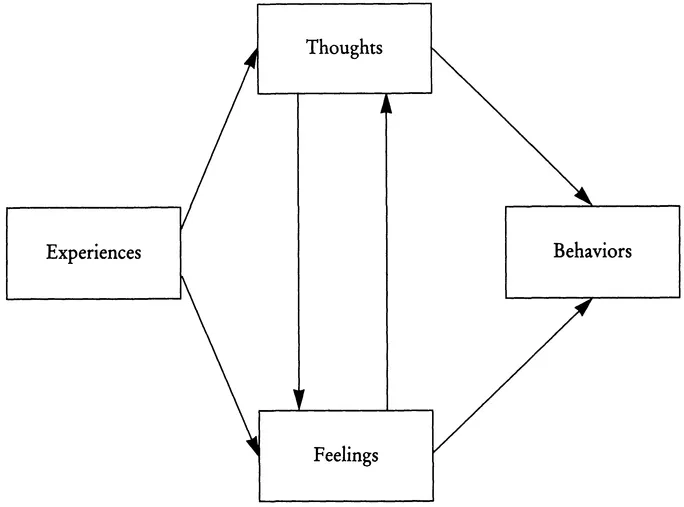

People's behavior also is strongly linked to views about justice and injustice. A wide variety of studies have demonstrated links between justice judgments and positive behaviors such as willingness to accept third-party decisions (Lind, Kanfer, & Earley, 1990; Tyler, 1990), willingness to help the group (Moorman, 1991; Organ & Moorman, 1993), and willingness to empower group authorities (Tyler & Degoey, 1995). Conversely, other studies have shown links between a lack of justice and sabotage, theft, vigilantism, and on a collective level, the willingness to rebel or protest (Greenberg, 1990a; Huggins, 1991; B. Moore, 1978; Muller & Jukam, 1983). In other words, how people feel and behave in social settings is strongly shaped by judgments about justice and injustice. This framework is shown in Figure 1.1.

Such justice judgments are of special interest to social psychologists because justice standards are a socially created reality. They have no external referent of the type associated with physical objects. Instead, they are created and maintained by individuals, groups, organizations, and societies. Justice judgments are central to such a social reality because they are the "grease" that allows groups to interact productively without conflict and social disintegration. Rawls (1971), taking a philosophical perspective, calls justice the "first virtue of social institutions." Behavioral scientists accord feelings about justice and injustice a central role in the ability of groups to maintain themselves.

The key argument is that judgments about justice mediate between objective circumstances and people's reactions to particular events or issues. Consider a specific case, examined at length in Chapter 3. Pritchard, Dunnette, and Jorgenson (1972) hired workers to work in a fictitious factory. These workers were led to believe that they were either fairly paid, overpaid, or underpaid. Those who believed they were fairly paid were the most satisfied. Other studies have shown that fairly paid workers are the most likely to stay on the job. In other words, workers' feelings and behaviors are shaped by what they think is fair.

FIGURE 1.1 Overall conceptual model

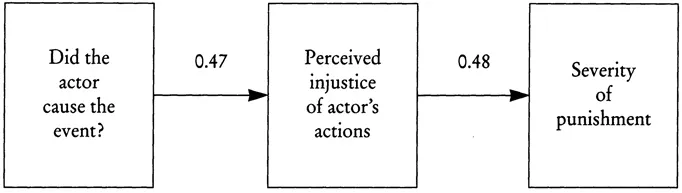

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that the impact of experiences is actually mediated by (i.e., flows through or is caused by) justice judgments. For example, Shultz, Schleifer, and Altman (1981) studied reactions to rule breakers. They demonstrated that there is no direct correlation between the characteristics of rule-breaking incidents and the magnitude of punishment responses following the rule breaking. Instead, as shown in Figure 1.2, it is the perceived injustice of a person's behavior that directly influences people's judgments of how severely the person should be punished, not whether the person actually caused the negative event.

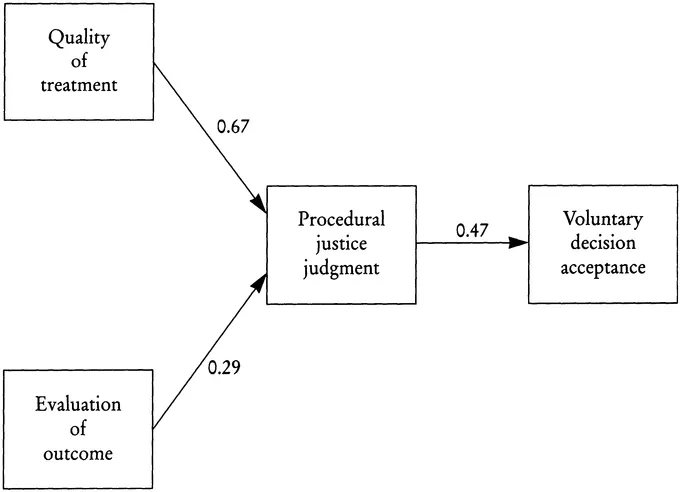

A similar example is found in a recent study by Lind, Kulik, Ambrose, and de Vera Park (1993) of disputants' reactions to awards in federal courts. This study examines why people voluntarily accept the awards they receive in pretrial mediation sessions instead of going on to formal trials. The quality of the outcome has no direct effect on such decisions. Instead it is people's judgments of the fairness of the mediation procedure that is directly related to willingness to accept (see Figure 1.3). In other words,

FIGURE 1.2 Reactions to rule breaking. SOURCE: "Judgments of Causation, Responsibility, and Punishment in Cases of Harm-Doing," by T. R. Shultz, M. Schleifer, and I. Altman, 1981, Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 13, 238-253. Copyright 1981 Canadian Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

FIGURE 1.3 The effect of justice on willingness to accept dispute resolution decisions. SOURCE: "Individual and Corporate Dispute Resolution: Using Procedural Fairness as a Decision Heuristic," by E. A. Lind, C. T. Kulik, M. Ambrose, and M. V. de Vera Park, 1993, Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 234. Copyright 1993 by Cornell University. Reprinted with permission.

they find that fairness mediates the relationship between decision favorability and the willingness to accept decisions.

Figures 1.2 and 1.3 are path analyses, which illustrate the causal relationship among a set of variables. The arrows presented show the influence that the variables on the left have on variables on the right. This direction of influence is indicated by the arrows and flows from antecedents to consequences. The absence of an arrow indicates no direct relationship. The value of a path analysis is that it can show influence that occurs through an intermediate variable (known as a mediating variable). For example, in Figure 1.2, judgments about an event's cause could potentially influence one's judgments about appropriate punishment either directly or by influencing one's judgments of moral responsibility. Although either type of influence is possible, the results presented in Figure 1.2 indicate that causal judgments have no direct effect on judgments about appropriate punishment. Instead, all of the influence of causal judgments flows through judgments about moral responsibility. Hence, judgments about causality only affect views about appropriate punishment to the degree that they shape judgments about moral responsibility.

Path diagrams also indicate the strength of the association between two variables. For example, in Figure 1.2, the numbers on the lines between variables indicate the strength of the association between two variables; higher numbers indicate greater influence. These numbers represent standardized coefficients (beta weights) adjusted to correct for differences in the scales used to measure different variables. Thus, the magnitude of different paths can be directly compared. The numbers range from zero (reflecting no association, as in the relationship between gender and the number of fingers a person has), to one (suggesting that one variable explains all of the variation in another, as in the relationship between gender and the ability to have children).

The examples given here focus on political and social issues. However, our concerns about social justice will be much broader. In many interpersonal situations, ranging from negotiating with parents to friends or lovers, people have been found to be very sensitive to issues of justice. Our goal is to consider the broad range of settings within which justice issues have been explored. As our review will show, this includes almost all settings in which people interact with one another, either as individuals or in groups.

Self-Interest, the Instrumental Model, and the Image of Human Nature

In addition to being important because it addresses central social psychological questions, social justice is important because its predictions are counterintuitive and contrary to the prevailing self-interest models that dominate the social sciences. The "rational" view of personal motivation that currently informs and influences much of social science and public policy assumes that people are motivated by self-interest, not by concerns about justice. Therefore, any departures from this rationality are both theoretically and socially important.

The dominance of the self-interest image of human nature within Western culture is striking. One example of this dominance is found in novels and films about situations in which people are stripped of their civilized facade by ex...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Part 1 Introduction

- Part 2 Is Justice Important to People's Feelings and Attitudes?

- Part 3 Behavioral Reactions to Justice and Injustice

- Part 4 Why Do People Care About Justice?

- Part 5 When Does Justice Matter?

- References

- About the Book and Authors

- Index