![]()

Part I

Laying the groundwork

![]()

1 Introduction

Risks of great power conflict in the 21st century

Harald Müller, Carsten Rauch and Iris Wurm

Introduction1

This book starts from a serious concern. We believe – contrary to John Mueller (1989) and contrary to the empirical trend (Lebow 2010; J. S. Goldstein 2011; Pinker 2011) – that conflict and war between great powers are still the most serious risk for the international community: diminishing conflict and war is not a natural law but the result of hard work and good luck. We are skeptical about the ability of current international institutions to handle the ongoing international power shifts that increase this risk. But here our pessimism ends and optimism begins because we and most of our contributors feel this situation is not beyond remedy. We specifically believe that the time-honored but not outdated concept of a concert of powers might be well suited to complement the current international order, increasing incentives for cooperation among the great powers, smoothing power shifts between countries and thus mitigating the risks that are inherent in great power relations. Concertation means a commitment by the leading powers to observe shared norms, hold regular consultations in an attempt to harmonize differing positions and develop common approaches – firstly, to avoid tensions among themselves that could escalate into military confrontation, and, secondly, to reach a consensus in multilateral institutions on issues of global interest. Such a minimum definition of “concert” allows flexibility as to the concrete shape of the institution while emphasizing its essential functions: to avoid the worst “common bad” and, over time, to create an environment conducive to working for the “common good.”

Since 2011, a research project brought together scholars from seven different countries representing the “West” and non-Western rising powers for deliberating whether and how great power cooperation might be feasible. That we could arrive at a consensus while the great powers were at loggerheads in several hot spots around the globe (Libya, Syria, South Chinese Sea, Ukraine) is a promising achievement. The collective result was the policy paper A Twenty-First Century Concert of Powers. Promoting Great Power Multilateralism for the Post-Transatlantic Era, where we delineated our agreements and strove for compromise (The 21st Century Concert Study Group 2014).2 This method ensured that the coauthors could endorse the general analysis and the core recommendations arrived at by the group, though not necessarily every single finding and advice.

This volume pursues a different objective. Here, we encouraged the contributors to emphasize the points they felt most strongly about in connection with a contemporary concert. Thus, readers will find in this volume an in-depth analysis of many issues to which the previous policy paper took a pragmatic approach, as well as chapters that are critical of either the historical concert or the concept of great power concert. Thus this volume does not promote a single position. Rather, it represents the pluralistic reasoning of some of the leading experts on contemporary global order.

This introduction will first lay out our conceptual groundwork and specify which theoretical perspectives and real-world developments inform our diagnosis that a great power concert is necessary to deal with the risks the world is facing today and expecting tomorrow. The focus in this section is on the dangers posed by ongoing power shifts among the most important great powers today and by existing hot spots. After that, we will offer a concise state of the art on the historical concert of powers and how IR theories interpret the concept. We will outline what we mean by a contemporary concert of powers. We conclude the introduction by providing an overview of the book’s sections and chapters.

Where we stand today: powers, power shifts and conflict hot spots

International power is in a state of flux concerning not only material power but the concept of power itself. There are discussions about hard and soft power (showing the importance of legitimacy in the international arena), about military and economic power and their relationship and about the power nuclear weapons afford or do not afford their possessors. These discussions contribute to the interpretation of today’s global power pattern but do not question the notion of a shift of relative power among states. While there is an impressive body of literature on the shift of power away from the state and toward organizations, NGOs and other non-state actors,3 this volume is concerned with the shift among the great powers. We claim, as a result of the changes noted in this literature, that this process has not lost relevance for humanity.

The frequently announced demise of the state is premature: First, it suffers from a distinct Western bias, which is ironic, because most functioning states are Western. True, in certain (but not all) Western states, the importance of the state vis-à-vis society is changing, and some Western states have delegated a portion of their sovereign rights to supranational bodies (e.g. the EU). However, this is only partly true for the West (witness the problems the EU is experiencing arising from nationalist populism). Soberly analyzed, the state is strong, stable and capable of delivering in the Western world. A newfound assertiveness is arising among non-Western “emerging powers.” Globalization has, at last, empowered these states to match formal sovereignty with meaningful capability. Having been colonized or otherwise subdued for the past centuries, they are keen on preserving every bit of their regained sovereignty. The same holds true for Russia, a superpower throughout the Cold War: During the Yeltsin years, the state lost some power to mighty oligarchs; under Putin, the state/government has reclaimed most of these powers. The alleged declining importance of the state actually affects a much smaller number of states than suggested by the postmodern Western bias, which is reinforced by some cases of spectacular state decay. Second, the rise of non-state actors does not affect all policy fields equally: While private actors (such as multinational corporations) might play an important role in the economic realm, and NGOs may push states and drive agendas on human rights and environmental issues, states and especially great powers are carefully maintaining their prerogative in international security. Private security companies, often regarded as signifying the decline of the state, usually are instruments used by states to economize on their monopoly of legitimate force and to exert more control over their societies (Krahmann 2010). The exceptions are transnational terrorist movements and warlordism, which pose real security challenges. While the numbers and types of actors have multiplied through globalization, great powers have retained their dominant role in the international power structure and thus in international security.

Great power relations are characterized by continuing security dilemmas and rapidly shifting global power structures. Such changes are, as history shows, dangerous but not hopeless. The first priority for global security governance is the relationship among the major powers. Whereas the capacity of great powers to provide common goods across all policy fields is limited, their capacity to produce “common bads”4 is unlimited: Just imagine the results of a war between today’s mostly nuclear-armed great powers! Even if other countries were not participating in the conflict, global streams of refugees, a breakdown of the world economy and nuclear radiation do not stop at the borders of neutral countries. Avoiding the common bad of a great power clash is our main motivation for finding a new mode for great power cooperation. If great powers cooperate, good prospects exist for security governance. If they do not work together, security governance is impossible, and a major violent conflict becomes likely. While the avoidance of a great power war is a value in itself, great power cooperation aiming at this goal might also be the precondition for producing additional common goods: States that are at one another’s throats are not inclined to cooperate for their mutual benefit. In a world where the fear of attack is strong, the problem of relative gains – who is gaining more from cooperation? – raises a substantial barrier to cooperative endeavors (Grieco 1990). Without such fear, cooperation, which serves both the common good and (consequently) the cooperating states’ own interests, represents rational behavior.

A power distribution assessment

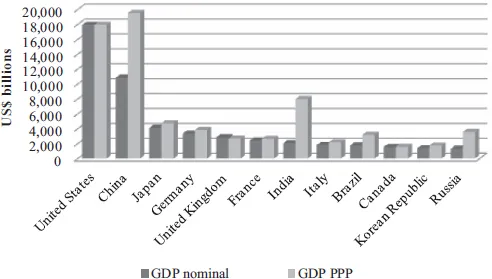

The world order has been for a long time a system of transatlantic hegemony. It started after World War II and figured prominently during the bipolar rivalry throughout the Cold War. After 1989, we left the era of bipolarity, but it is still not clear what era we have entered. Bipolarity was followed by the alleged “unipolar moment,” indicating that US preponderance would not be a lasting feature (Krauthammer 1990/1991). Realists such as John Mearsheimer (2001) or Christopher Layne (2006) expected other countries to balance US power. Others predicted lasting US hegemony (Beckley 2011; Brooks and Wohlforth 2011). In fact, US predominance proved to possess greater longevity than many expected (see figures 1–1 and 1–2). With the exception of population and territory, the US still leads in all power indicators, from GDP (gross domestic product) to military expenditure, and sits at the top of most power indices combining several single indicators.5

Political developments show, however, that US leadership is neither undisputed nor enforceable any more. Washington can manage international challenges neither on its own nor exclusively by the transatlantic framework, nor based on its increasingly disputed claim of normative leadership. The United States is also handicapped by the polarization in its domestic politics, which has displaced the bipartisan foreign policy consensus that served US leadership well during the Cold War (Fordham 1998; Trubowitz and Mellow 2011). Rising powers like China and India, in addition to Russia, advance their own preferences for managing the international system and demand a greater say in international decision making.

A power analysis that takes into account the development of GDP growth rates confirms this trend, revealing that major shifts in power are under way. While the US still has an advantage in absolute numbers, its (as well as Western European and Japanese) growth rates have been significantly lower than those of some rising powers (especially China and India) for more than two decades (see Table 1.1). Accordingly, the United States economy grew more slowly than China’s in all years between 1990 and 2015, than India in all but two years (1997 and 2000), than Brazil for 15 years, and than Russia for 13 years.

Figure 1.1 The top 12 powers according to 2015 nominal and purchasing power parity GDP rankings

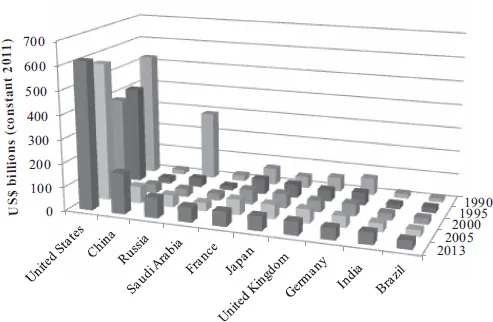

Figure 1.2 The top 10 powers according to 2013 military expenditures and the development of their spending over time

Table 1.1 GDP growth trends of important powers according to nominal GDP over time (in %) | | 1990–2015 | 1990–9 | 2000–9 | 2010–15 |

| United States | 2.43 | 3.23 | 1.82 | 2.12 |

| China | 9.72 | 10.01 | 10.30 | 8.29 |

| India | 6.52 | 5.77 | 6.78 | 7.33 |

| Russian Federation | 0.63 | −4.91 | 5.48 | 1.76 |

| Brazil | 2.51 | 1.88 | 3.39 | 2.10 |

| Japan | 1.08 | 1.47 | 0.56 | 1.30 |

| EU 4 (France, Germany, Italy, UK) | 1.47 | 1.96 | 1.16 | 1.17 |

Source: World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?view=chart, 01.10. 2016). Italics indicate powers rising in relation to the United States. Bold indicates powers declining in relation to the United States.

Projecting these GDP trends into the future indicates the establishment of some new power centers or poles and opens the possibility of a maximum power shift, a power transition, a change at the top of the international system. According to Goldman-Sachs, China’s GDP will overtake the US’s GDP by 2039, while India will be close behind (Wilson and Purushothaman 2003).

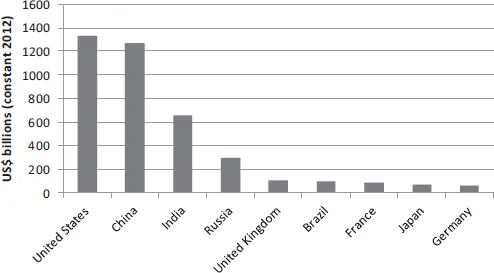

Power shifts will not be confined to the economic realm. In a 2014 study, the British Ministry of Defence forecast that by 2045 the China’s military spending will reach near parity with that of the United States, while Indian and Russian military expenditures will amount to 49 percent (2013: 8 percent) and 22 percent (2013: 14 percent) of US spending, respectively (see Figure 1–3).

Of course, these long-range projections involve many assumptions that may not hold up, but these uncertainties affect not only the trajectories of the challengers but that of the United States as well. Nonetheless, the United States remains the by far strongest power now and for the time being. Any attempt to regulate great power relations must thus take into account a dangerous triadic constellation: current US domination, power shifts already underway and a potential future power transition.

Even though power is shifting, the world is not standing still. Humanity faces global policy challenges that affect everyone. Some might still seem to allow – up to a certain point – for unilateral responses. Terrorism, for example, might be fought unilaterally, but the chances of success are higher when different countries work together. Other challenges such as climate change preclude unilateral response altogether; they will be mastered either collectively or not at all (Nye 2002). A third type of challenge, such as energy management, calls for a joint response to avoid potentially dangerous competition. The gravest risk to international society, however, remains a system-wide great power war.

Figure 1.3 Projection o...