- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1987, Regenerating the Inner City looks at the changes to Glasgow's East End and how industrial closures and slum clearance projects have caused people to leave. This is reflected across the western world, and causes severe blows to cities where these industries are located. The book draws on Glasgow's Eastern Area Renewal Scheme, the first big urban renewal project in Britain. The contributors to the volume come from a range of disciplines and form practical conclusions for policy-makers, and community activists. The book uses door-to-door surveys in Glasgow's east end, and interviews with community groups to gain an authentic understanding of the issue.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Regenerating the Inner City by David Donnison,Alan Middleton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Setting

1 GLASGOW AND ITS EAST END*

Introduction

Glasgow, still the largest city in Scotland, was once the second city of the British Empire: producer of coal, steel, textiles, ships, railways and armaments; headquarters of firms trading throughout the world; a workshop in which skilled workers by the thousands were trained – men and women who were capable of mobilising to demand social and political changes which left a lasting mark upon their country’s history.

That was the Glasgow of between sixty and a hundred years ago, now receding from living memory. Since then the city has lost one-third of its population – and an even larger proportion of its younger and more skilled workers. More than one-fifth of its labour force is unemployed, and only one-third of those still at work are producing manufactured goods; its mortality rates are high and its educational attainments low; its social classes live in separate neighbourhoods, segregated from each other to an unusually high degree … in short, it is a city in trouble.

But in recent years this has also become a city which has shown itself to be capable of healing the wounds of economic and social change: it has rebuilt itself on a bolder and larger scale than any other city in the world has attempted (attempted, that is to say, as a deliberate act of policy – not in the aftermath of destruction); it has created, in the process, a larger stock of publicly owned and subsidised housing, allocated on grounds of need, than is to be found in any other city in the market economies; it has rescued and repaired a marvellous heritage of Victorian parks, public buildings, houses and tenements, and enabled working people and pensioners who live in these buildings to stay there and enjoy the transformation; it has gone a long way to shed and surmount its reputation – only too well deserved – for drunken violence; it has become a thriving centre – second within Britain only to London – for music, drama and the arts; and it has launched more innovative social projects, more imaginative new experiments in public enterprise, than are to be found in most cities of its size and character.

The story we are going to tell deals only with one part of this city and one aspect of these developments – Glasgow’s east end and the scheme for renewing it. But the east end and its people stood once at the heart of the city’s economy and its political life. This then became the most derelict and devastated quarter of the city. The same kind of thing has happened in many other big, old cities. In Glasgow, as in other places, the attempt to rebuild the city and the morale of its people had to begin here: a broader renewal programme which neglected the east end would carry no conviction. So our story has a significance which extends far beyond Glasgow. It must start, however, with a brief description of this city and its east end. Unless we understand the origins of the problems to be discussed, we will not understand their solutions.

Glasgow and the decline of urban Britain

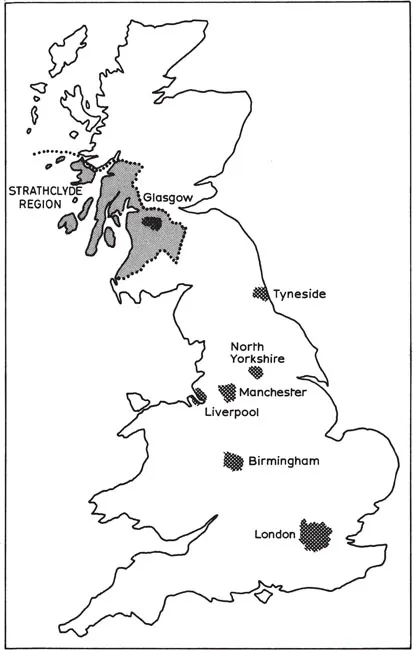

Glasgow is the principal city in the west of Scotland, standing at the centre of a group of smaller industrial towns around the mouth of the river Clyde (Figure 1.1). It has an elected District Council which is responsible for housing, environmental health, local planning, city parks and other services. Of these, housing is the most important politically and in the scale of the resources it deploys. More than half the city’s population live in public housing.

The Strathclyde Regional Council (SRC), covering the much larger area shown on our map, is another elected authority providing an upper tier of local government. It is responsible for strategic planning, education, personal social services, regional parks, major roads and other services. Of these, education is the most important in terms of the resources it wields, and probably in terms of its political significance.

Both these authorities are completely dominated by the Labour Party which in 1986 held fifty-nine of the sixty-six seats on the Glasgow District Council (GDC) and eighty-seven of the 103 seats on the Regional Council. Their similar political complexion does not prevent these authorities from quarrelling fiercely when their interests conflict, and both quarrel from time to time with the central government, even in periods when Labour holds a majority there too.

Figure 1.1 Britain’s conurbations and Strathclyde Region

Much of the central government’s powers have been devolved to Ministers, accountable to the Cabinet and Parliament in London, who operate from the Scottish Office in Edinburgh. Central powers in fields such as planning, housing, education, social work, the courts and prisons are administered in this way, often under separate Scottish laws. Social security, tax collection and defence are the main central functions for which control remains in London.

The central government has set up various agencies with powers to promote development in particular fields. Of these, the most important for our purposes are the Scottish Development Agency (SDA), with powers to promote industrial development and urban renewal; the Scottish Special Housing Association (SSHA), with powers to build and subsidise housing with the agreement of the local authorities concerned, both to meet special needs and to support local economic development; and the Scottish branch of the Housing Corporation which has powers to fund and regulate voluntary housing associations. More will be said about these bodies in later chapters.

Table 1.1 provides an approximate comparison of the scale on which the two local authorities and the three central agencies operate. It should be remembered, however, that the impact of their expenditure upon Glasgow cannot be read off from this table because they operate over different areas: the Housing Corporation and the SSHA operate all over Scotland, the SDA over urban Scotland, the Region over the area shown in Figure 1.1 (in which 46 per cent of Scotland’s 5.1 million people live) and the District within the Glasgow city limits (where 744,000 people live – 31 per cent of those in the Region).

Glasgow’s main features can be described by comparing them with those of other large British cities. Tendencies already beginning to appear between the wars set in more powerfully after the Second World War. They produced a shift in population and employment from the centres of big, old cities to their suburbs, from larger conurbations to smaller free-standing towns, and from the north towards the south. The main result has been a decline of the older northern conurbations and growth of free-standing towns and suburbs of the southern half of England (Hall, 1981, p. 66). There has also been a smaller shift from the west to the east, due perhaps to the decline of ship-borne commerce with America, and the growing importance of trade with the continent and of development associated with North Sea oil and gas.

Table 1.1 Current and capital expenditure of some public authorities, 1985–6 (£millions)

| Current | Capital | |

| SRC | 1,600,0 | 156.0 |

| GDC | 403.2 | 114.9 |

| SDA | 91.9 | 37.2 |

| SSHA | 89.4 | 45.3 |

| Housing Corpn | 1.9 | 104.2 |

By the 1970s it was clear that local authorities forming the central cores of conurbations in Britain with populations over one million had declined dramatically since 1951. The rate of decline for the first decade was only 3.7 per cent; but between 1961 and 1971 these urban cores lost 9 per cent of their populations (Hall, 1981, p. 15). By 1971 inner Liverpool had lost 400,000 people in fifty years (a decline of 57 per cent); inner London had lost 1.5 million since 1951 (–30 per cent). The same patterns were to be seen in the USA, but although the American and British definitions of inner areas are not strictly comparable, we can safely say that the scale of the loss has been much greater in Great Britain (Kirwan, 1981, p. 72). Within Britain, during the next intercensal period, 1971–81, it was Glasgow which suffered the greatest percentage decline of population of all the major conurbations (Table 1.2).

The loss of population from central areas by itself need not present problems. Policies for slum clearance and the building of new towns and peripheral housing estates have actively promoted this since the end of the Second World War. The loss of population can mean a fiscal crisis for metropolitan government, but this too can be accommodated by adequate centrally planned redistribution of funds. More important are questions about those who are left behind and their prospects of obtaining a reasonable standard of living. Any migration is likely to draw off the younger, the more skilled and the more enterprising people, and policies for dispersal often reinforced these effects. Meanwhile, private sector investment policies, motivated by technological change, the need to redeploy workers, and hence a search for cheaper and more docile labour, led to the decline of manufacturing employment in the inner areas, growth at the periphery and in the new towns, and an increasing regional imbalance as profits were reinvested in southern parts of the country.

Table 1.2: Population of Britain’s major cities

| Total 1981 000s | Change 1971–81 % | |

| Glasgow City | 766 | −22.0 |

| Greater London | 6713 | −9.9 |

| Birmingham MD | 1007 | −8.3 |

| Liverpool MD | 510 | −16.4 |

| Manchester MD | 448 | −17.5 |

| Newcastle MD | 228 | −19.9 |

Source: Census 1971, 1981; CURDS, Functional Regions Factsheet. No. 9, p. 1 (1984)

The outward flow of industrial investment and jobs from the centres of cities is now an accepted fact. Although Fothergill and Gudgin, for ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Plates

- Figures

- Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- PART I The Setting

- 1 Glasgow and its East End

- 2 Continuity, Change and Contradiction in Urban Policy

- PART II The GEAR Project

- 3 Urban Renewal and the Origins of Gear

- 4 Jobs and Incomes

- 5 Public Housing

- 6 Rehabilitating Older Housing

- 7 New Owner-Occupied Housing

- 8 Some Environmental Considerations

- 9 Access to The Health Services

- 10 Leisure and Recreation

- 11 Transport and Communications

- 12 The Management of Gear

- PART III Wider Perspectives

- 13 Lessons for Local Economic Policy

- 14 A Strategy for Education

- 15 Conclusions

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index