![]()

1 Introduction

Research problem

This book seeks to assess the extent to which individuals and corporations wishing to invest in the agricultural and mining sectors of the Federated Malay States (FMS) from 1896 to 1909 were affected not only by the policies of the Colonial Office,1 but also by the varying attitudes and decisions made by the Residents,2 the Resident-Generals3 and the High Commissioners.4 There had been in fact a serious adversarial relationship between these local administrators and investors that obstructed potential capital investments in the Malay States.

This argument raises further contention that although the British administration of the FMS deemed capital inflow to be crucial, commercial elites had to face obstructions in their ventures due to excessive bureaucracy. As a matter of fact, investment procedures in the agricultural and mining industries involved high degrees of hierarchical discretion within the colonial administration. Typically a top-down approach, investment policies were first developed by the official mind in London (Colonial Office), to be eventually carried out by the ‘man on the spot’, who was the British administrator of a particular state. The business community had indeed been instrumental in the policy-making process, but was not on every occasion a successful lobbyist. These three groups did, however, play direct and indirect roles in regulating the activities of both local and foreign investors in the Malay States of Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang.

Before the 1870s, the Colonial Office opposed British investment as business turnover resulting from the transaction was bound to strengthen the position of the Sultans.5 There were certain quarters that supported British investment and others who were against it. This premise is spelt out clearly in Sinclair’s article titled “Hobson and Lenin in Johor: Colonial Office Policy towards British Concessionaires and Investors 1878–1907”, which shows that conflicts arose among officials at various levels of colonial administration in economic matters. The view often expressed was that increasing prosperity of the state and the strength of the Malay polity would not have justified British intervention (Sinclair, 1967a: 336). However, the governors of the Straits Settlements desired British capital penetration into the Malay States for the reason that they personally had a lot to gain from such a move. This was evident when Sir Charles Clifford, the Chairman of the Malay Peninsular Agency Limited, who was the cousin of Governor Frederick Weld, was given a concession. Sir Frank Swettenham, the ex-Governor who retired in 1903 had also acquired several concessions from the Sultan of Johore (Sinclair, 1967a: 343). The above cases, which happened in the ‘Unfederated’ Malay State of Johore, provide examples of the kinds of conflict and varying attitudes among British officials; between the Colonial Office and British officials; between investors and British officials; and between British officials and the Malay Rulers with regard to the expansion of British capital in the Malay States.

There was a clear lack of policy-making coordination between the Colonial Office, the High Commissioner, and the Resident-General, Residents as well as various other officers at the Federal and State levels. This must indeed sound strange, as the formation of the Federation was required to be based on a well-conceived plan. A Federal Scheme that outlined the jurisdiction and role of the various officers and the periodic issuance of Circulars from the office of the Resident-General should have left no room for doubt as to the distribution of responsibilities.

The Federation led to hitherto non-existent problems for the British at the administrative level. After 1896 the British administrators had to deal with decisions of the Colonial Office, which began to play an important role in these territories. This was to be expected simply because the Federation represented a territorial entity that was likely to become a nation-state and therefore deserved due attention as an important part of the British Empire.

Scope

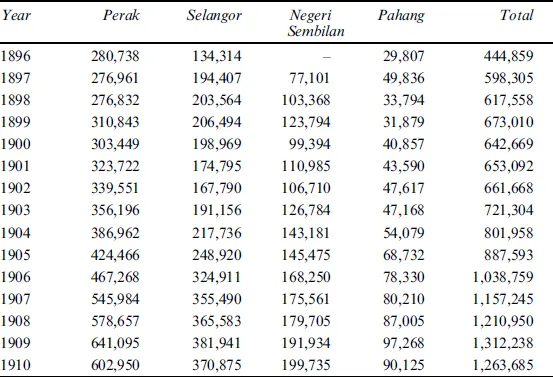

The discussion covers the period between the formation of the Federated Malay States in 1896, and the formation of the Federal Council in 1909.The formation of the FMS in 1896 coincided with an increase in investments within the Malay States. This is obvious from Table 1.1 showing the revenue gained by each of the four states from the agricultural and mining sectors in the period between 1896 and 1909.

Table 1.1 Land revenue of Federated Malay States (premium, rents and licences for agricultural and mining lands), 1896–1910 value in Straits Dollars

Source: Federal Estimates, 1896–1910.

With the formation of the Federation, one would have expected policy matters to be sorted out between the High Commissioner, the Resident-General and the Resident.6 In reality, however, there were many occasions when the Resident-General discarded the opinion of the Resident, and instances when the High Commissioner overruled the suggestions of both the Resident-General and the Resident. The Rulers and the State Councils also lost their influence to the Resident-General and High-Commissioner, not to mention the officials of the Colonial Office.

The year 1909 represents an effective cut-off year for bringing the analysis to a conclusion, for by this time, the growing awareness of the problems affecting capital investment (due to dissenting opinions amongst officials at various levels of British administration) was vexing the Colonial Office and steps were then taken to redress the situation through administrative reform.

Under the Federal Council which was formed in 1909, the High Commissioner was the President and the chief administrator of the Federated Malay States. The title of Resident-General was replaced by that of Chief Secretary to the Government. Despite the change of title, the functions remained the same. The Chief Secretary, like the Resident-General continued to act as agent and representative of the British Government under the High Commissioner.

The Federal Council brought together the Residents, Resident-Generals and High Commissioners to discuss and resolve any contentious issues and to implement common policies in the four states. The spirit of the Federation was, therefore, better expressed in the structure provided by the Federal Council which provided little free play for autonomous decisions.

This introduction is followed, in Chapter 2, by an analysis of British economic activities in the Malay States from 1800 to 1896. It is a period of great significance to the British in Malaya, which saw the consolidation of the Straits Settlements, the transfer of administrative control from Calcutta to London and British intervention in the Malay States. Particular mention is made of the policy of the Colonial Office and the role of the men on the spot with regard to investment. Chapters 3–6 deal with various case studies on administrative impediments to the Malay States in the years between 1896 and 1909, beginning with the situation in Perak (Chapter 3); followed by Selangor (Chapter 4); Negeri Sembilan (Chapter 5); and Pahang (Chapter 6). The final chapter presents an evaluation of British capital penetration in the Malay States.

Significance of this publication

The book is important for its contribution to our understanding of Malaysian economic history in the period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Numerous writings have dealt mainly with the development of various industries without a detailed examination of how individual and corporate investors from the mining and agricultural sectors fared in the Malay States. This study uncovers the truth that investors were badly affected by the conflicts between the Residents, Resident-Generals and High Commissioners in the early stages of British capital inflow in the FMS.7 The discussion also includes bureaucratic problems confronting investors, such as restrictive land rules and clashes between liberal and rule-bound British officials in the FMS administration.

In pursuing this theme, the writer has consulted various records housed at the National Archives of Malaysia, including those of the High Commissioner’s Office, the State Secretariat of Pahang and Negeri Sembilan, plus the Colonial Office. These sources provide insights into the real problems faced by the local and foreign capitalists and the extent to which the Colonial Office and the relevant personalities were involved in either hindering or encouraging the free movement of capital in these states.

In short, this study researches an area that has long been neglected by historians. It is expected to contribute towards an understanding of British economic imperialism at work in the late nineteenth century, and the laying of the foundation for the management of commercial enterprises in the Malay States.

Indeed, writings on Malaysian economic history in the nineteenth and early twentieth century have mostly been focused on tracing the development of the main economic commodities such as tin and rubber without looking into the problems faced by foreign and local investors in the respective sectors.8 The other works on the Malayan economy have chosen to concentrate on issues involving the export sector, agricultural and industrial development, unemployment, distribution of income and wealth, human factors in economic development as well as on money and finance. All these works focus on twentieth-century Malaysian economic history without discussing the administrative and bureaucratic constraints on the promotion of private enterprise in the Malay States.9

The more comprehensive works on the development of British Malaya from 1896 to 1909 include Chai Hon-Chan’s The Development of British Malaya, 1896–1909 (1967), which gives a thorough account of developments in the Federated Malay States between 1896 and 1909. The work also covers economic development in agriculture and tin mining but with no particular emphasis on problems faced by investors and financial elites.

J.G. Butcher’s The British in Malaya 1880–1941: The Social History of a European Community in Colonial South-East Asia (1980) explains how Europeans adapted to life in Malaya and the general position of the Europeans in Malayan society. It helps us to understand how British personalities perceived investment by foreigners and locals – whether they were more accommodative to foreign companies compared to local firms.

Emily Sadka’s The Protected Malay States, 1874–1895 (1968) focuses on the evolution of the Residential System from the period of British intervention to the formation of the Federated Malay States. The work investigates a number of issues such as the shaping of imperial policy and strategy and the role played by the local administration in the decision to intervene in the Malay States; development of the government system; communications; and the formulation of immigration, labour and land policies. Most importantly the study contains an interesting discussion of the manner in which the Secretary of State, the Governor of the Straits Settlements and the Residents exercised authority in the Protected Malay States. An analysis is also given of the economic policies and their effects on economic development and social change. To a certain extent, Sadka’s work highlights some of the problems faced by the High Commissioner, Residents and Resident-General in the Malay States. However, Sadka’s work deals only with the brief period between the beginnings of British intervention in 1874 until the signing of the Federation Treaty in 1895. This research aims to go beyond 1895, to analyse the results of the Federation in terms of the ambivalence it created with regard to capital investment in the Malay States, and ends with the setting up of the Federal Council in 1909.

Eunice Thio’s British Policy in the Malay Peninsula 1880–1910 (1969) studies the formation, implementation and impact of British policy in the Malay Peninsula between 1880 and 1910 but its focus is not on the problems of British capitalist interests. The author also examines in detail the various agents involved in policy formulation – the officials in the Colonial Office and the men on the spot. Although Thio discusses some of the problems faced by investors, her primary focus is on the state of Selangor. However, Thio did not consult some of the major primary sources such as the High Commissioner’s Office, and State Secretariat files such as those of Selangor, Negeri Sembilan ...