- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1986. Independent Spirits is about the intellectual world of the humbly-born in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain, focussing on plebeian, or working- and lower middle-class spiritualists. This book is an important study which throws light on the idealism and search for knowledge that were so central in plebeian circles and in certain, very important parts of the labour movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This title will be of interest to students of history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Independent Spirits by Logie Barrow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Germination

A American beginnings

Spiritualism, as a belief, centres on purported conversations with the ‘spirits’ of physically dead people. Such beliefs have occurred in many or most periods and cultures. But the start of spiritualism as an ‘ism’ is always dated to precise incidents, at Hydesville near Rochester in upstate New York during 1848. From these ‘Rochester rappings’, support spread quickly for the spiritualist version of these events throughout the USA. In America, the spiritualist movement ‘seems to have reached a highwater mark around 1854–55’.1 In the mid 1850s it suffered a widespread ‘recantation movement’ (as contemporaries called it); but it survived, and remained a strong current there. The basic history of American spiritualism can be scanned in a number of recent and often highly readable books.2

I am not setting out to stick my hooves into ground as well ploughed as this. But a few aspects are worth comparing or contrasting with their English equivalents. In general, much has been said about the pliably pentecostalist temper of upstate New York before and during these decades – about its status, in other words, as a ‘burnt-over district’.3 Yet, however swiftly spiritualism spread through such areas (whether sparsely log-cabined, or migration- and industry-based boom-towns like Rochester), it also had a largely similar history in the very different environment of the East-coast cities. In other words, it spread more broadly than the revivals. And in any case, Rochester itself was not merely ‘the most thoroughly evangelised of American cities’, but also ‘among the few cities outside the old seaports that supported free-thought newspapers’ and where the birthday of Tom Paine, the English-born deist, could be openly celebrated during the mid 1830s.4 Perhaps, in general, the upstate environment and the urban, whatever their physical differences, had certain social and intellectual overlaps: the geographical and social mobility was, during these decades, intense even by American standards. So there was particularly little to undermine interest among Bostonians or Philadelphians in developments which had originated at or towards the frontier of settlement.5

Any contrasting of the American environment with the English involves what anthropologists currently call ‘culture contact’. As Nelson notes,6 there are two aspects of Amerindian cultures which may possibly have influenced the growth of spiritualism: Shamanism and the belief in guardian spirits. We can also note that Indians were important among the early teachers of Samuel Thomson, the pioneer of a system of medical herbalism7 which, as ‘medical botany’ or ‘Thomsonianism’, had an impact before and during the period of spiritualism’s arrival in England, often among the same sort of people and in similar geographical areas (as I will note later).8 Nelson also notes9 a similarity with certain African beliefs in spirit possession. Given that these certainly resurfaced sooner or later in Haiti, Brazil and elsewhere, they were presumably not unknown among those slaves (or their descendants) who had happened to be sold to English-speaking owners. Not only in ex-French New Orleans were ‘many coloured persons… found among the mediums’,10 but also elsewhere in the South, fear of spiritualism’s social implications was probably one factor in the hostility shown by white mobs and by some legislators. Recently, Peter Linebaugh has argued loud and long that blacks contributed to a political radicalism, common to much of the lower classes in all the, at least English-speaking, countries around the Atlantic basin.11 Linebaugh’s claims may, for all I know, be somewhat excited, but they remain exciting. Further, if Africans and their descendants can at last even be argued to have contributed to the political culture of other poor people, why not (conceivably) also to the religious too? (And if Africans, why not Amerindians, likewise?) True, Protestantism may be a less fertile ground than the Catholicism of New Orleans – or, say, of seventeenth-century Spanish-speaking Colombia12 – for direct kinds of syncretism (a word denoting a combination of previously disparate beliefs). But can it – particularly at its extreme fringes – rule out indirect kinds? Arguably not. The last two sentences may therefore apply somewhat to England too.

And there are other senses – quite apart from Linebaugh – in which the differences between the USA and England were, particularly during this time, ones of degree more than of kind. Firstly, in both countries there was often a widespread passion for self-education. In many north-eastern states of the USA (including New York), adult literacy during the early-middle nineteenth century is said to have topped 95 per cent; and there was also a massively successful ‘lyceum’ movement or ‘Association of Adults for the Purpose of Mutual Education’.13 (Later, ‘lyceums’ was to be the name of spiritualist Sunday schools, particularly for children, on both sides of the Atlantic.) This educational passion was not necessarily allied with political and religious radicalism; but often it was. And even when it was not, it could still encourage coolness towards any intellectuals associated with the upper classes. Thus autodidacts (those who make their education their own concern, irrespective of social superiors) are particularly likely to hunger for new world-systems, or to build their own. Some vaunt their down-to-earthness even while flapping around on wings of speculation or special revelation.

A minor and (for once) perhaps overwhelmingly American variation on such tendencies was the detailedness with which Andrew Jackson Davis – the founding seer of American, and later indirectly of plebeian British, spiritualism – described the landscape of the ‘Summerland’ or next world. Here, he often gave not only the topographical measurements – suitably imposing – but also the names. It was sometimes unclear who told him these: they sound vaguely Latinité – though, in a somehow infantile way, not quite. All these visions, we are told, were dictated in a trance. Davis, ‘the Poughkeepsie seer’, had had little formal schooling; most of his upbringing had been in a recently settled area which remained a major corridor for fresh settlers on their way through westwards. If Welsh-speaking Indians were still a respectable hypothesis among even the likes of Thomas Jefferson, then the mundane geography of many settlers (and of those dreaming of following them) could be equally speculative.14 Thus Davis’s celestial geography may, in part, have echoed the geographical meditations and plain rumour-mongering of generations of settlement-minded people, many of them very autodidact. If so, Davis combined the hunger of visionaries the world over for new worlds, with the hunger of many would-be settlers for new landscapes.

Another difference of mere degree between the USA and England is the presence of a number of sects whose beliefs overlap with and had foreshadowed some of spiritualism’s. The Shakers’ communities (eighteen of them, comprising about 6,000 members during the sect’s peak in the 1850s) were all in America,15 though Shakerism had begun in Britain and continued to recruit there through the nineteenth century, as we will see. Another sect which had originated in visions but which, like the Shakers, had sought organisational stability by discouraging further such revelations was the Swedenborgian. Swedenborg himself (1688–1772) had apparently16 been against founding a new church at all and, during the nineteenth century as much as before, some of those who more or less accepted his teachings retained their positions and posts within older organisations – including occasional Church of England, Unitarian and other clergymen. But the Swedenborgians’ ‘New’ or ‘New Jerusalem’ Church was, by the early nineteenth century, a stable though minor feature of the religious landscape in both England (as we shall see soon) and New England. A further current which contributed to spiritualism and which had some early adherents on both sides of the Atlantic was Unitarianism (or the belief in one God rather than in a Trinity). In the long run, many Unitarians tended to evolve towards a universalist position (or the belief that all people were saved – i.e. in some way evolved – after death). One spiritualist who remained officially a Universalist was the Reverend J. M. Peebles, a much-travelled American Unitarian who for decades was friendly with English plebeian spiritualists and who sought to strengthen their links with American Shakers.

B England and Keighley

In 1853, David Richmond returned to Britain. He was by now (as we shall see during chapters 5 and 6) a middle-aged autodidact craftsman who had gone through various phases of communitarianism (including Owenite) and religious belief (including deist) on both sides of the Atlantic. He had been in America since 1842, and a Shaker since 1846. He was hardly the first person of such a background to join the Shakers.17 He claims18 that this group had attracted him by its ‘spirituality’; but possibly he was also attracted not only by their communal life-style but also by their asceticism:

J. M. Peebles

A busy link between American and British spiritualists, Peebles had earlier left the Universalist ministry when his congregation objected to his spiritualism. Sometime professor at the Eclectic Medical College in Cincinnati, he edited a succession of spiritualist periodicals and authored numerous pamphlets, including one against vaccination. He visited Britain not only as spiritualist but also as sympathiser with the Shakers.

A busy link between American and British spiritualists, Peebles had earlier left the Universalist ministry when his congregation objected to his spiritualism. Sometime professor at the Eclectic Medical College in Cincinnati, he edited a succession of spiritualist periodicals and authored numerous pamphlets, including one against vaccination. He visited Britain not only as spiritualist but also as sympathiser with the Shakers.

he himself had been teetotal since 1836 and vegetarian since 1841. Richmond had quickly learnt of the Rochester rappings and had visited the family in whose house they had been heard, the Foxes. What seems to have been going on in relation to his 1853 trip is that he had persuaded the Shakers to allow it (and, for all we know, to finance it) as a ‘mission’ for Shakerism but that, once he felt free of them, he missionised more – or more directly – for spiritualism. True, he sometimes attracted attention by donning the Shakers’ ‘peculiar garb’. But this may have been no more than a gimmick: he would have known how uneasy they were about further ‘revelations from the spirit’.

Richmond’s list of contacts (at least as he remembered it 32 years later) seems to have been weighted heavily towards current and former followers of Robert Owen – the now very aged pioneer of communitarianism, socialism, religious ‘infidelity’ (which, during the 1850s, was being renamed secularism) and much else. Richmond’s first meeting was in his natal town of Darlington,

by invitation of secularistic teetotallers. At Keighley was the next Secularistic Society who listened to [his] Gospel, and embraced spiritualism. London was the next Secular Society, at the City Road Rooms [the then H.Q. of London secularists, where he argued with their current leader Holyoake, and their future one, Bradlaugh] and also at the Secularist Rooms in Whitechapel, and afterwards at Middlesboro’ [sic] by invitation of the Secularists.

The prominent individuals whom he visited also included Lloyd Jones (an Owenite and cooperator) and Robert Owen himself. Owen had been converted to spiritualism shortly before meeting Richmond.

We can glean some idea of what Richmond attempted, in at any rate the larger gatherings of secularists, from the case of Keighley – a middling-sized textile town in Pennine Yorkshire. Here, ‘getting the Secularists of the town together, he did not leave them till he had turned them [no proportion mentioned] into Spiritualists, in some degree by his own mediumship, but largely by their own sitting in circle under his guidance.’ ‘Table manifestations’, we are told, ‘were obtained through mediums in the body of the audience by [sic] Richmond who delivered an explanatory address.’ He was subsequently to be known among Keighley spiritualists as ‘Father David’, and officiated on more than one occasion as their founder.19

But the reason why Keighley allows us such glimpses is simply that it seems to have been by far David’s most successful port of call. Why is unclear. So, even, is why it attracted him in the first place. True, he had lived in Leeds and Bradford during the late 1830s, the time when he became an Owenite. And there is a very vague assertion by at least one local historian that Owenism had

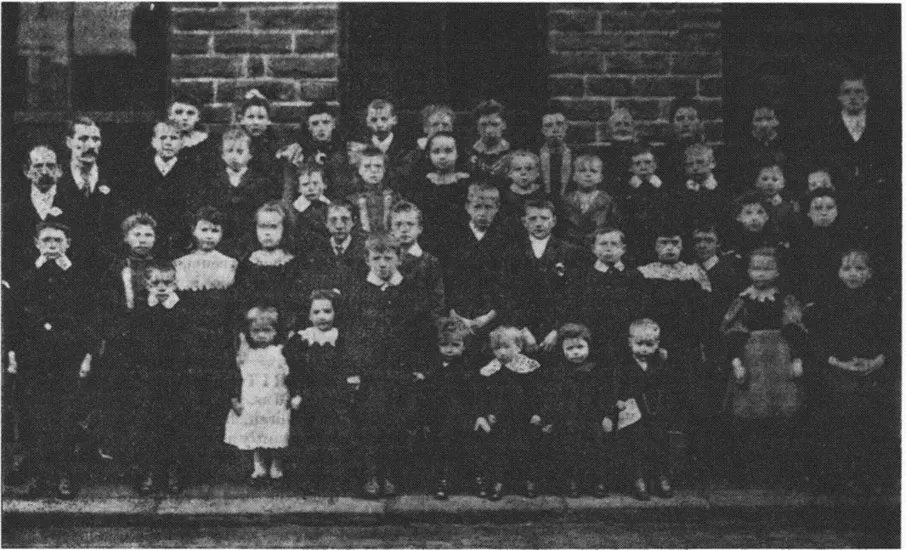

Members and officers of the Keighley Lyceum

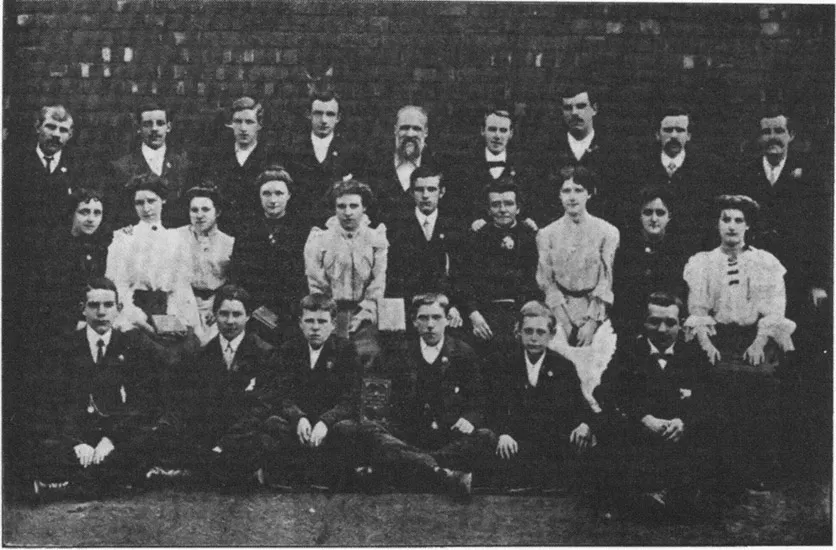

The officers of the Sheffield (Attercliffe) Lyceum

not been forgotten in and around Keighley.20 At any rate, when Richmond approached David Weatherhead, the outcome was this spectacular-sounding ‘demonstration’. It took place in the radical citadel, the Workmen’s Hall. ‘Weatherhead became convinced of the truth of spirit intercourse and at once became a keen convert.’21 Possibly also, Richmond discerned his potential: David Wilkinson Weatherhead had been ‘connected with every radical movement in Keighley in the first half of the 19th century’. He had been one of the key local leaders in the Ten Hours movement, of the attacks on the new workhouses, and of Chartism; in 1843 he had been impr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Dedication

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Germination

- Chapter 2 Owenism and the millennium

- Chapter 3 Nottingham and cabala

- Chapter 4 The problematic of imponderables

- Chapter 5 Plebeians and others

- Chapter 6 Presence and problems of democratic epistemology

- Chapter 7 Healing

- Chapter 8 Bridging the great divide

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index