![]()

Introduction: understanding the consequences of the Arab uprisings – starting points and divergent trajectories

Raymond Hinnebusch

School of International Relations, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK

This introduction sets the context for the following articles by first conceptualizing the divergent post-uprising trajectories taken by varying states: these are distinguished first by whether state capacity collapses or persists, and if it persists, whether the outcome is a hybrid regime or polyarchy. It then assesses how far starting points – the features of the regime and of the uprising – explain these pathways. Specifically, the varying levels of anti-regime mobilization, explained by factors such as levels of grievances, patterns of cleavages, and opportunity structure, determine whether rulers are quickly removed or stalemate sets in. Additionally, the ability of regime and opposition softliners to reach a transition pact greatly shapes democratic prospects. But, also important is the capacity – coercive and co-optative – of the authoritarian rulers to resist, itself a function of factors such as the balance between the patrimonial and bureaucratic features of neo-patrimonial regimes.

What are the consequences of the Arab uprisings for democratization in the Middle East North Africa (MENA) area? The Arab uprisings that began in 2010 had, as of the end of 2014, removed four presidents and seemingly made more mobilized mass publics an increased factor in the politics of regional states. It is, however, one thing to remove a leader and quite another to create stable and inclusive “democratic” institutions. The main initial problem of the Arab uprisings was how to translate mass protest into democratization and ultimately democratic consolidation. Yet, despite the fact that democracy was the main shared demand of the protestors who spearheaded the uprisings, there was, four years later, little evidence of democratization; what explains this “modest harvest”, as Brownlee, Masoud, and Reynolds1 put it?

Neither of the rival paradigms – democratization theory (DT) and post-democratization approaches (PDT) – that have been used to understand the Middle East have come out of the uprisings looking vindicated. The PDT theme of authoritarian resilience, in its focus on elite strategies for managing participatory demands, has clearly overestimated their efficacy, neglected their negative side effects and underestimated the agency of populations. Yet, the democratization paradigm has also since suffered from the failure of revolt to lead to democracy.2 Rather than either a uniform authoritarian restoration or democratization, the uprisings have set different states on a great variety of different trajectories. As Morten Valbjorn argues in his contribution, grasping this complexity requires moving beyond both DT and PDT.

This introductory article first conceptualizes the variations in post-uprising trajectories. It then seeks to explain how far the starting point – the features of both regimes and oppositions in the uprisings – explain these post-uprising variations, specifically looking at: (1) anti-regime mobilization, both its varying scale and capacity to leverage a peaceful transition from incumbent rulers and (2) variations in authoritarian resistance to the uprisings, a function of their vulnerabilities, resources and “fightback” strategies. This will provide the context for the following contributions which focus on post-uprising agency, that is, the struggle of rival social forces – the military, civil society, Islamists, and workers – to shape outcomes. These contributions give special attention to three states that are iconic of the main outcomes, namely state failure and civil war (Syria); “restoration” of a hybrid regime (Egypt); and democratic transition (Tunisia). In the conclusion of the special issue, the evidence is summarized regarding how the power balance among post-uprising social forces and the political, cultural, and political economy contexts in which they operated explain variations in emergent regime outcomes.

Alternative post-uprising trajectories

The various outcomes or trajectories of the Arab uprisings appear best conceptualized in terms of movement along two separate continuums: level of state consolidation and regime type. Moreover variations in the states’ starting points on these dimensions at the time of the uprisings will arguably affect trajectories.

As regards state consolidation, if uprisings lead to democratization this ought to strengthen states in that it would accord them greater popular consent, hence capacity to carry out their functions. However, the initial impact of the uprisings was state weakening, with the extreme being state collapse or near collapse (Libya, Syria), where democratization prospects appear to be foreclosed for the immediate future. Yet, even amidst such state failure, new efforts at state remaking can be discerned. Such competitive state making in MENA was first conceptualized by the North African “father” of historical sociology, Ibn Khaldun, and adopted by Max Weber, who identified the “successful” pathways to authority building dominant in MENA, notably the charismatic movement which tended to be institutionalized in patrimonial rule, perhaps mixed with bureaucratic authority. Ibn Khaldun’s “cycles” of rise and decline in state building appear better suited to MENA than the idea of a progressive increase in state consolidation; indeed the history of state making in MENA has described a bell-shaped curve of rise and decline,3 with the current state failure merely a nadir in this decline.

As for regime type, if one measures variations in regimes along Dahl’s two separate dimensions by which power is distributed – level of elite contestation and level of mass inclusion4 – a greater variety of regime types is possible than the simple authoritarian-democratic dichotomy and this variation may explain both vulnerabilities to the uprising and likely outcomes. Patrimonial regimes low in both proved quite viable in the face of the uprisings, as in the persistence of absolute monarchy in the tribal oil-rich Arab Gulf. Polyarchy, high on elite contestation and mass inclusion, has been rare in MENA. The region has, however, experienced various “hybrids” in which some social forces were included in regimes in order to exclude others: thus, the populist authoritarian regimes of the 1960s expanding popular inclusion within single-party/corporatist systems, in order to exclude the oligarchies against which they had revolted; when populism was exhausted in the 1980s, they turned “post-populist”, marginally increasing elite contestation (for example, by co-opting new elements into the regime and allowing some party pluralism and electoral competition) in order to co-opt the support needed to exclude the masses. Given that the uprisings initially precipitated both increased elite contestation and mass inclusion, movement toward polyarchy, that is, democratization, appeared possible. However, rather than linear “progress” toward increased contestation and inclusion, hybrid regimes with different combinations of opening and closing at elite and mass levels are more likely.

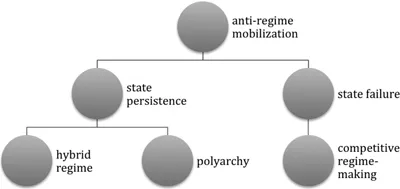

Figure 1 adumbrates the alternative trajectories the uprisings have so far taken. Where the state fails, the outcome is an authority vacuum, with extreme levels of elite contestation propelling mass mobilization along identity lines, with rivals competing violently to reconstruct state authority, often pitting the most coercive remnants of state establishments against charismatic Islamist insurgencies (Syria, Libya, Yemen). The rival regimes are likely to be hybrids constructed around patrimonial or charismatic leadership and remnants of bureaucratic state institutions, with very limited elite contestation within such regimes-in-formation and with identity groups mobilized around included victors, with the losers coercively excluded.

Figure 1. Pathways of post-uprising states.

Where the state does not collapse, two outcomes are possible: the establishment persists and restores its authority or it is taken over by new democratic leadership. In the first case, the new post-uprising regimes are likely to be hybrids, mixing elements of co-optation, coercion, and pluralism – electoral authoritarianism – with middle levels of inclusion. Equally, the state establishments may take advantage of widening identity cleavages within society, such as that between secularists and Islamists, to divide and rule, including one segment in order to exclude the other, as in Egypt. Only Tunisia approximates the second case of democratic transition.

Path dependency: uprising starting points and subsequent trajectories

To understand the starting point from which the uprising trajectories departed, we need to assess their drivers – the vulnerabilities of authoritarian regimes and the dimensions of anti-regime mobilization.

Roots of crisis, authoritarian vulnerability

Two theoretical approaches give us insight into the roots of the crisis that exploded in the Arab uprisings. In modernization theory (MT), the challenge authoritarian regimes face is that once societies reach a certain level of social mobilization (education, literacy, urbanization, size of the middle class) regimes that do not accommodate demands for political participation risk they will take revolutionary forms unless otherwise contained by exceptional means such as “totalitarianism”. MENA states were in a middle range of modernization where democratization pressures were significant but could still seemingly be contained and indeed had been in the republics for decades, first by a generation of populist, more inclusive, forms of authoritarianism (diluted imitations of Soviet “totalitarianism”), later by post-populist “upgrading”. MT would locate the roots of the uprisings in a growing imbalance between social mobilization and political incorporation.5 There were some levels of imbalance in all of the republics but the depth of the imbalance arguably affected regime trajectories. Thus, levels of social mobilization as measured by indicators such as literacy and urbanization were lowest in Yemen and highest in Tunisia; yet political incorporation was sharply limited in Tunisia, while co-optation via controlled political liberalization was much more developed in Yemen. The very strong imbalance in Tunisia may help explain the rapid, thorough mobilization and quick departure of the president, as well as the more thorough transition from the old regime; conversely, the stalemated outcome in Yemen may be related to the lower levels of social mobilization combined with still viable traditional practices of co-optation.

Second, Marxist theory locates the crisis in a contradiction between the productive forces and the political superstructure. Gilbert Ashcar6 argues that the uprisings were stimulated by the contradiction between the imported capitalist mode of production and the blockage of growth by crony capitalist rent seeking patrimonial regimes that failed to invest in productive enterprise, resulting in massive numbers of the educated unemployed. Indeed, the Arab uprisings were a product of the republics’ evolution from a formerly inclusionary populist form of authoritarianism to post-populist exclusionary versions under the impact of global neoliberalism; this move was particularly damaging in the republics, compared to monarchies, because they had founded their legitimacy on nationalism and a populist social contract, both of which they abandoned in the transition to post-populism. The cocktail of grievances that exploded in the uprisings was produced by the growing economic inequality produced by the region’s distinct combination of International Monetary Fund-driven “structural adjustment” and crony capitalism. Inequality was driven by region-wide policies of privatization, hollowing out of public services, reduction of labour protections, tax cuts, and incentives for investors. Yet economic growth remained anaemic, principally because, while public investment plummeted, private investment did not fill the gap and indeed MENA was the region with the highest rate of capital export, in good part because capital was concentrated in a handful of small-population rentier monarchies that recycled their petrodollar earnings to the West. This was reinforced by the loss of nationalist legitimacy as regimes aligned with the West. Protests against this evolution had been endemic, beginning with the spread of food riots across the region in the 1980s – but, at the same time the regimes’ strategies of “authoritarian upgrading” meant to make up for the exclusion of their popular constituencies, such as divide and rule through limited political liberalization, co-optation of the crony capitalist beneficiaries of neoliberalism, and offloading of welfare responsibilities to Islamic charities – had appeared sufficient to keep protests episodic or localized enough to be contained by the security forces, preventing a sustained mass movement.7

Bringing the modernization and Marxist approaches together, we can hypothesize that in the short term authoritarian upgrading had reached its limits and had begun to produce negative side effects. Thus, the wealth concentration and conspicuous consumption of crony capitalists was paralleled by growth of unemployment among middle-class university graduates – the force that spearheaded the uprisings. The attempts of aging incumbent presidents to engineer dynastic succession and an over-concentration of wealth and opportunities in presidential families alienated elites as well. On the other hand, political liberalization had stalled or been reversed in the years just preceding the uprisings, with, for example, manipulated elections becoming more a source of grievance than of co-optation.8 In addition, the republics suffered leadership de-legitimation from the very long tenures of many presidents.

Ultimately, the particular depth of the crisis in each country was a function of the relative degree of economic blockage and the imbalance between social mobilization and political incorporation. However, states were set on varying trajectories by the specific initial features of the uprising in each, shaped by the interaction between varying levels of anti-regime mobilization and varying levels of regime resilience in the face of this mobilization.

Variations in mobilization across cases

While the literature on the uprisings has noted the apparently greater immunity of the monarchies to anti-regime mobilization, as compared to the republics, much less appreciated are the vari...