- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This title was first published in 2001. Aiming to open up a new perspective on the study of threats and risks, this text combines insights from the thematically linked but academically disassociated fields of security studies, risk studies and crisis management studies. It provides case studies of key agents, arenas and issues involved in the politics of threats. In addition to the traditional unit of analysis - national governments - this book takes into account non-governmental agents, including public opinion, the media and business.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Threat Politics by Johan Eriksson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Opinion in Focus

1 Risk Perceptions: Taking on Societal Salience

LENNART SJÖBERG

Threats and risks have come to be an important focus in current policy debates and decision-making. A crucial issue, which has been the topic in much of Risk Studies, is how people perceive risks, and what factors affect such perceptions. Several distinctions are made in this chapter, especially between personal (risk to oneself) and general (risk to others) risks that appear to have quite different dynamics. What people demand in terms of risk mitigation is mostly related to consequences of adverse events, not risks or probabilities or even to 'riskiness' of activities. In many cases, personal responsibility is seen as drastically smaller than those of the government.

Threats or Risks? A Note on Terminology

This book mostly employs the word threat, but this chapter is about risk. The position taken here, however, is that if there is a difference between the two, it is hardly of any practical importance. One could argue that the word threat refers to a hazard close in time and very likely to strike, as suggested by some active in this field, but that is hardly a position that is easy to defend on the basis of everyday language. In technical language we are of course free to define terms as we wish, at the peril of not being understood in everyday discourse. Therefore risk and threat can be treated as synonyms.

Other misunderstandings concern the word risk. Some people seem to believe that the word is reserved for a special technical use, such as expected value or probability of an adverse event.1 All this is very confusing and illustrates the danger of not making a clear distinction between natural and technical language. Therefore—as noted in the introduction to this book—risk is seen as equitable with threat and similar words, and thus defined with reference to how it is used in everyday contexts. What relations it may have to subjectively perceived probability is an open empirical question. In accordance with the framing perspective adopted in this volume, I am only concerned with perceived2 risk, which may or may not be related to 'real' risk.

In an international perspective, the UK Royal Society commissioned a group of researchers to do a review of risk perception, analysis and management back in 1991 (Royal Society Study Group 1992). This report gave rise to a very strong reaction and heated debate still being mentioned in UK literature. Social scientists tended to take a constructivist standpoint, while the natural scientists took a realist standpoint. However, it is obvious that both must be pertinent in risk discussions. First, risk is an expectation of an (adverse) event, and hence it is a social construction like all expectations. It is in our minds and nowhere else. Second, it is an expectation about something, i.e. about an external event, actor or structural condition of some kind (cf. Introduction). Hence, it refers to reality. Risk analysis must therefore proceed along both lines, both to understand how people perceive and construe risk, and what the issues risk perceptions are referring to. Even if there is a desire for understanding what the 'real risks' are, one must always remember that what real risks are of concern is not God given but a matter of social judgment. And how people react to the risk information that scientists provide is also a matter for the social scientist to analyse, as is, indeed, the question of how scientists and experts themselves frame risks.

The Salience of Risk: Public Opinion vs. Experts

Risk perception has been a topic of interest to researchers and policy-makers at least since the end of the 1960s, beginning with a seminal article by Starr (1969), Considerable research has been devoted to the question of how people perceive risks. The reason for this large and sustaining interest is probably that it is widely believed that risks and risk perceptions are important to policymakers. Even if perceived risk is weak as an explanatory variable of individual behaviour, it is probably important for policy related attitudes (Sjöberg, 1999d; Sjöberg, 1999e). For example, it has been found that Swedish parliamentarians have tripled their initiatives in risk related legislation since the 1960s (Sjöberg and others, 1998).

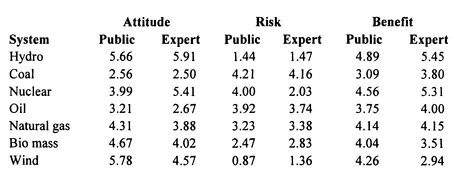

How salient are risks? In a Swedish survey concerned with risk perception and the attitude to various technologies for energy production (Sjöberg, 1999e), a number of questions about various energy production systems, their risks and benefits were posed to members of the general public and to nuclear waste experts. The answers to these questions provide a picture of the general differences in attitude that characterised the experts and the public with regard to these issues. The means are given in Table 1.1.3

Table 1.1 Means of attitude (good-bad), perceived risk and benefit of energy production systems (scale 1-7)

There were some interesting differences between the two groups in Table 1.1. First, experts were more positive than the public to nuclear power, whereas the public was more positive to biomass, natural gas and wind. Second, the public considered nuclear power to be much more risky than the experts did. Third, experts perceived most systems as more useful than the public did, with the exception of bio mass and wind, where the public gave higher ratings.

Ratings of attitude to the seven energy production systems were regressed on judgments of risk and benefit of these systems (see Tables 1.2 and 1.3).

Table 1.2 Regression analysis of the public's attitude to energy production systems

| System | β risk | β benefit | Adjusted R2 |

| Hydro | -0.474 | 0.137 | 0.255 |

| Coal | -0.544 | 0.071 | 0.294 |

| Nuclear power | -0.692 | 0.192 | 0.608 |

| Oil | -0.552 | 0.075 | 0.297 |

| Natural gas | -0.681 | -0.036 | 0.474 |

| Biomass | -0.567 | 0.136 | 0.328 |

| Wind | -0.492 | 0.217 | 0.283 |

Table 1.3 Regression analysis of experts' attitude to energy production systems

| System | β, risk | β, benefit | Adjusted R2 |

| Hydro | -0.030 | 0.170 | 0.000 |

| Coal | -0.242 | 0.083 | 0.027 |

| Nuclear power | -0.290 | 0.291 | 0.178 |

| Oil | -0.271 | 0.174 | 0.089 |

| Natural gas | -0.478 | 0.225 | 0.244 |

| Biomass | -0.451 | 0.322 | 0.329 |

| Wind | -0.313 | 0.524 | 0.355 |

The level of explained variance in these analyses was relatively high, with some exceptions. In both cases it is seen that risk was the more potent explanatory dimension. This was particularly clear for the public. There is an interesting exception for experts judging nuclear power. In this case, benefit obtained a β value at the same level as risk. Hence, it appears that experts' attitude to nuclear power is less risk dominated than the same attitude held by the public. As was shown in Table 1.1, the experts also rated nuclear power risk as much lower than the public did.4

Why does risk take on salience? We have just seen risk to be a dominating factor in accounting for attitude, benefits being much less important. In related studies, we found that people are more easily sensitised to risk than to safety (Sjöberg and Drottz-Sjöberg, 1993). Mood states are more influenced by negative expectations than by positive ones (Sjöberg, 1989a). People seem to be more eager to avoid risks than to pursue chances.

The Impact of Framing: Personal vs. General Risk

Research on risk perception has usually employed an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I: OPINION IN FOCUS

- PART II: ACTORS IN FOCUS

- PART III: ISSUES IN FOCUS

- Conclusion: Towards a Theory of Threat Politics

- Bibliography

- Index