eBook - ePub

Politics And Change In Alkarak, Jordan

A Study Of A Small Arab Town And Its District

- 191 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Politics and Change in AI-Karak, Jordan first appeared in 1985, it was part of a sparse, but growing, literature about intermediate-level politics in the Arab Middle East. A number of works had been written on national politics, focused primarily on the capital and national institutions and figures. A few village studies, which used the discip

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Politics And Change In Alkarak, Jordan by Peter Gubser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Environment, History, and Economics

Environment1

THE governorate of Al-Karak, of which the district forms part, lies east of the southern half of the Dead Sea in the East Bank of the Kingdom of Jordan. Conveniently, the historical area of Al-Karak, as a political entity, is very much the same as the present district.

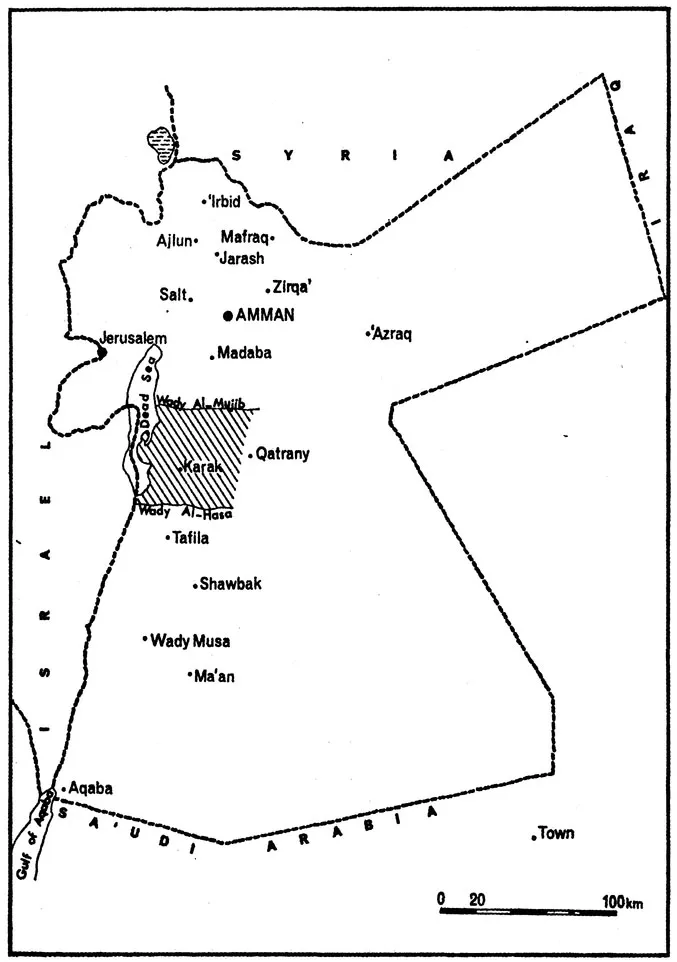

Map 1, p. 9, indicates Al-Karak's geographical position in relation to the rest of Jordan. The Balqa', which includes the town of Madaba, borders it on the north; and to the south lie the district of Tafila and the governorate of Ma'an. The Dead Sea lies on the west and the Syrian (or North Arabian) Desert to the east. Each of the borders forms a formidable, but not impassable, barrier. The Wady Al-Mujib and Wady Al-Hasa, both dropping from heights of 900 m to well below sea-level, are the northern and southern boundaries. The excessively saline water of the Dead Sea cuts off the west, and the east fades into a virtually rainless desert.

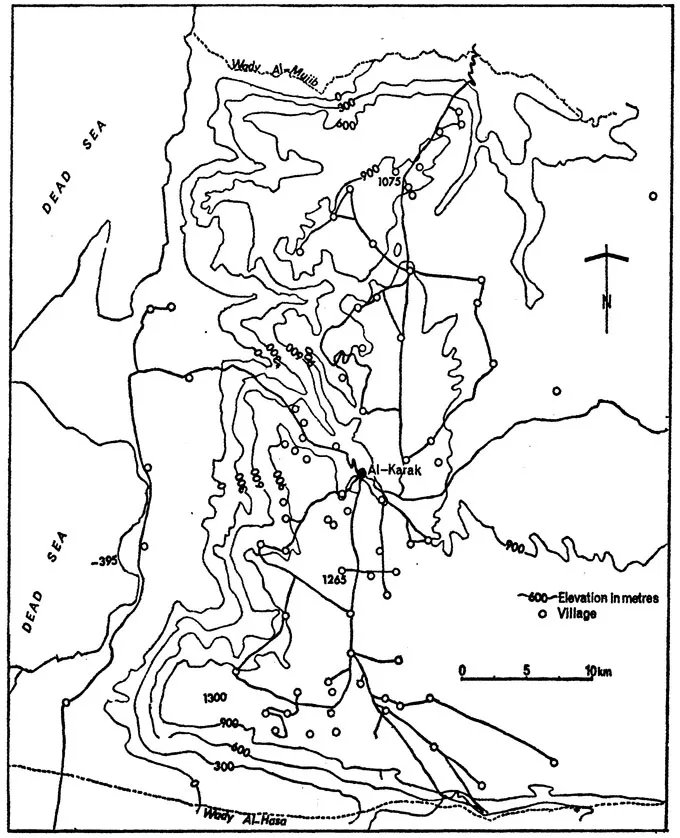

The district of Al-Karak covers approximately 2,850 square km, with an average elevation of about 770 m. From the east the Syrian Desert rises to form high limestone plateaux, with an average elevation of 1,100 m, and hills which reach 1,300 m, forming the backbone of the area. Then the terrain drops precipitously to the Dead Sea, 395 m below sea-level.

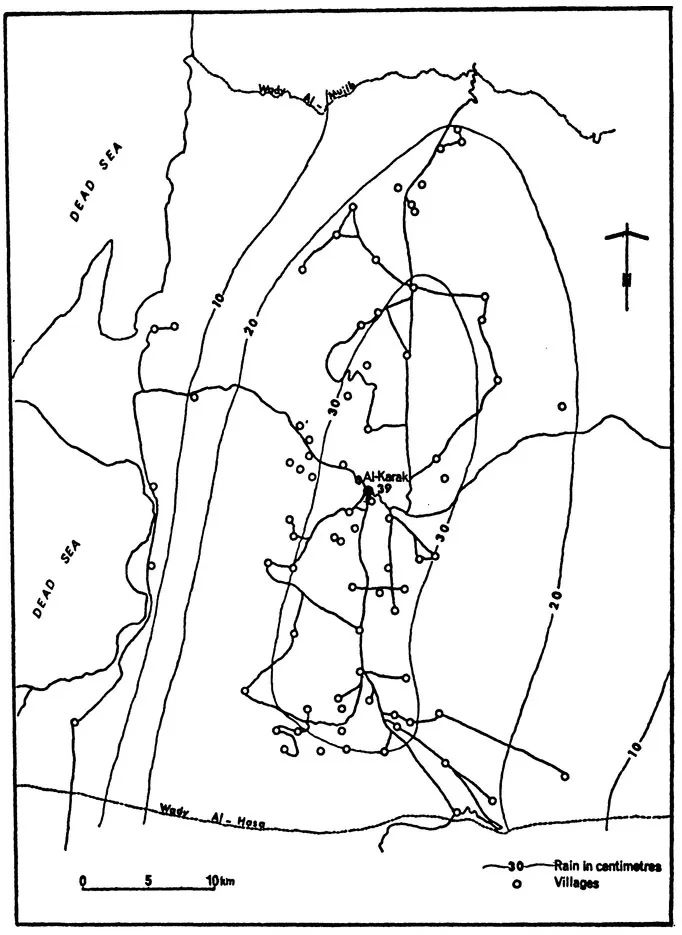

As a result of its varied geography, Al-Karak has three distinct types of climate. The region next to the Dead Sea is characterized by warm, short winters, with rainfall varying from 5 to 15 cm, and extremely hot, dry summers. There is no spring or autumn. The central part of the area averages 35 cm of rain from November to April, but in erratic yearly amounts, 10 cm, for example, in 1962/3 but 50 cm in 1963/4. In the winter the temperature often drops below freezing; the summers are mild with a few hot days. The eastern edge of the district receives much less rain, 10-20 cm, and its temperature variation is much like that of the central area.

MAP 1. Jordan—East Bank—Al-Karak (shaded)

MAP 2. Al-Karak: to show contours

MAP 3. Al-Karak: mean Annual Rainfall

The land on the edge of the Dead Sea has proved fertile with irrigation. On the plateau the soils are in some places light and shallow, suitable only for grains, and in others deep and suitable for fruit-growing. The semi-desert area is used for marginal cereal cultivation when the rains are sufficient. Both here and in the precipitous northern, southern, and western areas of the district, sheep and goats forage on the sparse grass. Large forests once existed in the region, but both the Ottomans and the indigenous population have ravaged them. Reafforestation is now promoted and financed by the central government.

Rain follows the contours of the land. The village population also lies mostly within the 30 cm rain-belt. It will be seen later on in this study that those living outside this belt are also on the margins of the district's political life and hold little political power.

History

Al-Karak was involved in most of the major historical movements in the Middle East owing to its central position, bordering on, or lying close to, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Arabia. It was strategically important because of its naturally fortified position on one of the major communications routes of the Middle East. Only in this century have new modes of transport and warfare by-passed it completely. The town has been variously known as Kir of Moab, Kir Haraseth, Petra Deserti, Charac-Moba, Castle of Crac, Pierre du Désert, and Al-Karak. The area first appeared in history in 2400 B.C., during the Bronze Age, with an advanced sedentary agricultural civilization, but this suddenly and inexplicably disappeared in 1800 B.C. About 600 years later, a new civilization, the Moabite Kingdom, developed. It was then that the site of the present-day town of Al-Karak was first settled and fortified. Since then it has probably been continuously inhabited, with possible short periods of interruption. In the tenth century B.C. the Moabites were defeated by, and afterwards paid tribute to, David of the Israelite Kingdom, but under the great Moabite king Mesha the area regained its freedom in 840 B.C. During the late ninth, eighth, and seventh centuries it fell under Assyrian influence and during the next two centuries under the Persians. Alexander the Great conquered it with the rest of Asia Minor, and after his death Ptolemy of Egypt controlled it, along with Palestine and southern Syria.

In the second century B.C. the Moabite civilization gave way to that of the Nabataean Arabs which was centred in Petra, south of Al-Karak. This was a trading kingdom and at times a buffer state between the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria. In the middle of the first century B.C. Pompey established Roman control over Transjordan, soundly defeating the Nabataeans in 32 B.C., but the kingdom was able to retain a large measure of internal independence as a vassal state of Rome. Internal rule changed hands in A.D. 106, when various Arab tribes conquered the region and dissolved the Nabataean Kingdom. In the fourth century A.D., when the Emperor Constantine (324-37) was converted to Christianity, most of Transjordan was also converted and Al-Karak became part of the bishopric of Petra. It came under the Ghassanides in the sixth century as part of the Byzantine Empire. In the early seventh century it fell briefly to the Persians, but soon reverted to Byzantine control, only to fall to the Muslim conquerors.

The first battle between the Muslims and the Byzantines was fought in the Al-Karak area at Mu'ta in A.D. 629, but the Muslim forces were heavily outnumbered and defeated. The soldiers of Islam are said to have fought heroically. Their tombs in what is now the village of Al-Mazar, close to the field of battle, are considered to be holy and are a place of pilgrimage; and much of the land aroun dAl-Mazar is owned by the 'Awqaf institution, which rents it to local peasants who also have the right of inheritance over it. After the Muslim conquest Al-Karak was ruled as part of the various Islamic dynasties, but in the twelfth century the Crusaders conquered the region. Baldwin I started a fortress-building programme of which Al-Karak was a part, and its imposing citadel, known as 'Pierre du Désert', was finished during the reign of Baldwin II. Later, Al-Karak became the centre of Renaud de Châtillon's rule in Transjordan. This Crusader was continually opposed by Saladin and more than once earned his wrath by breaking treaties. When Al-Karak came under attack by Saladin's forces in 1183 Renaud decided to defend only the fortress, so the town was quickly taken, but Saladin suddenly withdrew because of better opportunities elsewhere. Peace was established, but Renaud broke it in 1187 by raiding rich caravans. After Saladin had defeated the Crusaders at the Horns of Hattin on the Sea of Galilee in July 1187, and had put the untrustworthy Renaud to death, Al-Karak was besieged and starved out in October of that year. The Ayyubids ruled the area in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries and this was the last stronghold to fall to the Mamlukes under Baibars. Except for brief occupation by Arab forces, it continued under Mamluke rule until the Ottomans defeated them in 1517.

The Ottomans1 set up a government in Al-Karak and garrisoned Shawbak, south of the area. Also, significantly, the pilgrimage route to Mecca, which for centuries passed directly by Al-Karak town, was moved to what later became the Hijaz railway route on the eastern edge of the district. This dramatically diminished the importance of the area, and perhaps partly explains the willingness of the Ottoman government to let Al-Karak retain virtual independence (with some exceptions) from the mid-sixteenth century until 1893.

Towards the latter part of the reign of Sulayman the Magnificent (1520-66), a powerful tribe of Al-Karak, the Tamimiyya, rebelled against Ottoman rule.

As it would have cost much money to send a regular force to Kerak the Wali of Damascus asked Yusef al-Nimr of Nablus to deal with the situation. Yusef at once collected a force and marched to Kerak where he soon restored order, and those of the Temimiya who were not killed fled to Hebron. A new governor was then sent to Kerak and one of the brothers of Yusef, either Othman Agha or Hasan Agha, was appointed to the command of the troops.

Very shortly after this, the new governor became disloyal and with the support of the Arabs in his district declared his complete independence of Ottoman rule (Peake, History, pp. 84-5).

The Ottomans then tried to regain control through negotiations, but failed. 'After this the Turks made no further attempt to reestablish their rule in Kerak and Shobek and so the brother of Yusef al-Nimr became chief of the district' (Peake, ibid., p. 85). His descendants and the local Ottoman soldiers in Al-Karak became known as the 'Aghwat tribe. In 1678/9 and again in 1710/11 the Ottomans sent punitive expeditions against the Karakis, but did not establish permanent rule in the area (Laoust, pp. 219, 231).

From this point to the reoccupation of the region by the Ottomans in 1893, the history of Al-Karak, with a couple of exceptions, is the history of local tribal politics, relations with the neighbours of Al-Karak, new tribes entering the area, and the rise of the Majaly tribe to power. Initially the 'Aghwat, which, together with its allied tribes, was known as the 'Imamiyya, ruled the area. The alliance's chief rival was the 'Amr, a semi-nomadic1 tribe, which may have significantly increased in size in the late seventeenth century through the addition of distant relatives from the Hijaz.

The Majaly originally came to Al-Karak as merchants from Hebron. In the ensuing years they acquired some land, and increased their numbers by bringing in their Hebroni relatives. Then, from the eighteenth century onwards, a succession of brilliant political leaders were able to raise the tribe from a virtually powerless position to that of the leading power of the region and a mover in the whole of Transjordan. In the early 1700s they allied themselves with the 'Amr and massacred the 'Imamiyya alliance, eliminating it as a force in the area. However, the Majaly were definitely the junior partners in the alliance with the 'Amr. While in power the 'Amr were noted for cruelty and ruthlessness, not only in exacting money from the local tribes but also in their brutal personal treatment of the Karakis.

The opportunity for the next round in the rise of the Majaly power came when the Bany Sakhr, a noma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- PREFACE TO THE ENCORE EDITION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1. Environment, History, and Economics

- 2. Fabric of the Traditional Political Society

- 3. Dynamics of the Traditional Political Society

- 4. Fabric of the Contemporary Political Society

- 5. Dynamics of the Contemporary Political Society

- 6. Conclusion: Change and Integration in the Political System

- APPENDICES

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX