![]() SECTION ONE ECONOMICS AND CLINICAL GUIDELINES

SECTION ONE ECONOMICS AND CLINICAL GUIDELINES![]()

Chapter One

Economics and Clinical Guidelines – Pointing in the Right Direction?

Anne Ludbrook and Luke Vale

Introduction

Clinical guidelines aim to promote effectiveness and improve the quality of care. It is accepted that recommendations provided by guidelines should be evidence based if their implementation is to improve the quality of care (CRD, 1999).

Current practice on the inclusion of economic information in guidelines is variable. The Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines in the US has recommended the inclusion of information on the cost implications of alternative strategies for the management of the clinical problem under consideration (Field and Lohr, 1992). The North of England Evidence Based Guideline Development Project has incorporated economics into its methodology (Eccles et al., 1998). Other guideline methodologies have not explicitly included economics (Mann, 1996) and some are currently exploring the best way to incorporate economics (SIGN, 1999). The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recognised that there has been a lack of cost-effectiveness information in clinical guidelines and has included cost-effectiveness as one of 10 key principles underpinning its guideline development process (NICE, 2000).

The introduction of an economic framework into clinical guidelines raises a number of issues. Whilst clinicians may find it difficult to resist the argument in favour of clinical guidelines that are designed to promote effective practice, the question of cost-effective practice appears to be more problematic. The difficulties lie in at least two areas; the first relates to the methods for incorporating economic information and the second is the interpretation of such information and the potential conflict between what is most effective and what is most cost-effective practice. In this chapter it is argued that guidelines will be more useful for decision-makers if they are formulated to include economic information.

The first part of the chapter briefly describes why the economic perspective is important. The next section is primarily concerned with technical issues relating to the ways in which economics can be incorporated into guidelines and the type of information that should be included. The issues addressed in this section are the quality of economic evidence available and the importance of identifying both the volume and cost of resources involved. The final section deals with the decision-making context. It looks at how the same guideline information can be interpreted and implemented at a local decision-making level, where budgets may be fixed in the short term, and at a national priority setting level, where there may be more potential to vary funding. The chapter also discusses how the scale of the implementation influences the guideline development process and the problems inherent in unthinking use of cost-effectiveness ratios and cost-per-quality adjusted life year (QALY) thresholds in decision-making.

The Economic Perspective

The definition of the ‘best’ practice that guidelines are designed to promote depends upon many factors (effectiveness, cost, efficiency, etc.) all of which may be of relevance to decision-makers and should be included within the guideline. A decision-maker should be interested in efficiency because they have the task of maximising the benefits (health gain) obtained from the resources they have available. An intervention is efficient if the benefit provided is greater than that forgone had the limited resources been used for other desirable uses. This represents the economic concept of opportunity cost, where cost is defined in terms of the benefits that could have been obtained from the opportunities forgone. Opportunity cost is not always easy to measure but the principle that underlies it is important, as it emphasises benefits as the key factor in decision-making. Economic appraisal provides a means of providing information about efficiency as it involves the comparative analysis of alternative courses of action in terms of both their costs (resource use) and effectiveness (health effects) (Drummond et al., 1997).

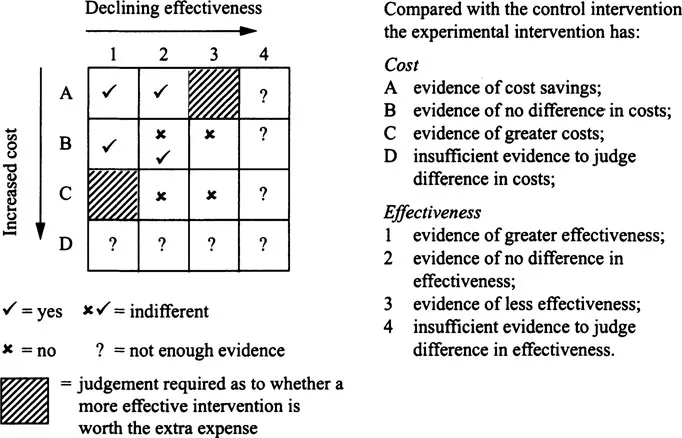

This approach is not particularly contentious when one intervention can be shown to provide greater health benefits at the same or less cost. However, where an increase in health benefit is achieved at greater cost, judgements have to be exercised about the value of additional benefit and how it compares with other uses of health care resources. Figure 1.1 illustrates how data on costs and effectiveness can be brought together in an economic appraisal to aid the judgement about whether one intervention should be preferred to a comparator.

Figure 1.1 | Matrix linking evidence on effectiveness and cost |

In squares A1, A2 and B1, the intervention is more efficient than a comparator and is assigned a ‘Yes’ response to the question outlined in Figure 1.1. In squares B3, C2, and C3 the procedure is less efficient than the comparator and this receives a ‘No’ response to this question. In the shaded areas (A3 and Cl), a judgement would need to be made as to whether the more (less) costly intervention is worthwhile in terms of the extra (lower) benefits to patients. Square B2 is neutral, as there is no difference in either costs or effectiveness.

In clinical guidelines, best practice is often defined in terms of effectiveness alone. In terms of Figure 1.1 clinical guidelines provide information on rows 1 to 4. However, recommendations based on effectiveness data alone could be modified if cost data were also considered. In most situations the inclusion of cost data clarifies the choice that should be made. This is most apparent in the second column of the matrix where the interventions under consideration have equal effectiveness. In this situation differences in cost provide the means of distinguishing between the interventions.

Only in two situations will there be any real tension between guidelines based on cost and effectiveness data and those based on effectiveness data alone (areas C1 and A3), as it is in these areas that the use of both cost and effectiveness data may potentially reverse recommendations. However, even in these situations the ‘cost-effectiveness’ data are open to interpretation and judgement has to be exercised as to whether a more effective and costly intervention should be recommended above a less effective and less costly one. The provision of information on cost-effectiveness does not make the decision for the decision-maker; rather, it allows decision-makers to make more informed judgements.

As Figure 1.1 illustrates, economic appraisal is conceptually straight forward but as the rest of this chapter highlights there are several issues that need to be addressed in both the production and interpretation of this type of data.

Technical Issues in Incorporating Economics into Guidelines

If economic criteria are to be used to aid decision-makers, economic evidence needs to be identified or derived and, once obtained, consideration is required on how to appraise and present it in a form useful to decision-makers.

Identifying the Evidence

Methods to identify economic studies are evolving (CRD, 1996; Mugford, 1996). Standard sources for references of published economic evaluations include bibliographic databases; in addition to MEDLINE and EMBASE there are a number of other potential sources economic appraisal references, such as CINHAL, ECONLIT, SIGLE, and Social Science Citations Index. The choice of which databases to interrogate is dependent upon the nature of the topic for which economic analyses are sought. The search strategies used also need to be adapted for each database, as they depend upon the indexing terms the database uses.

Other potentially useful sources of economic literature exist. The Office of Health Economics, together with the UK and International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations, produce the Health Economic Evaluation Database (HEED). HEED contains approximately 19,000 articles of which about 9,000 are reviewed using a structured reporting format that provides a breakdown of the methodology and results of the study. The smaller NHS Economic Evaluation Database also seeks to identify published economic appraisals. However, in addition to summarising their methodology, results and conclusions it also seeks to critically appraise them in a rigorous and systematic way. In addition to the electronic databases, there are a number of secondary journals such as Evidence Based Health Policy and Management and ACP Journal Club, which review and critically appraise published economic appraisals.

In some situations, the existing literature may be inadequate to address the issues raised by the guideline and in such cases primary research may be required. This may be obtained by extending the results of existing evaluations (see for example the Cochrane Economic Methods Group guidance for using the results of Cochrane reviews to provide evidence for subsequent economic evaluations (CEMG, 1999)).

Assessing the Quality of the Evidence

Guidelines for the practice and critical appraisal of economic appraisal of health interventions exist (Drummond and Jefferson, 1996; Gold et al., 1996; Association of British Pharmaceutical Industries, 1994; Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment, 1997; Commonwealth of Australia, 1995). Unfortunately, there is considerable variability in the quality of published economic appraisals (Udvarhelyi et al., 1992; Mugford, 1995; Jefferson and Demicheli, 1998; Gerard et al., 1999). This makes it difficult to compare studies and has implications for attempts to synthesise and transfer data to other settings (Jefferson et al., 1996; Rigby et al., 1996).

The object of synthesising data is to provide information that is relevant to the decision-making context. Numerous options exist for combining data, ranging from the simple narrative synthesis through to quantitative synthesis of economic evaluations (Jefferson et al., 1996) and modelling (CEMG, 1999). However, regardless of the approach taken and in common with evaluations limited to efficacy or effectiveness, economic appraisals frequently encounter uncertainty in both the method of application and the interpretation of their result (Briggs and Gray, 1999).

Role of Evidence in Economic Evaluation

It has been suggested that economic evidence need not be as strong an evidence base as data on clinical effectiveness (Johnstone et al., 1999). The strength of evidence required is dependent upon the extent of uncertainty and the nature of the decision-making context. In terms of economics in guidelines, the evidence provided must be robust enough for judgement to be exercised. For example, if plausible changes in estimates of efficiency do not change the judgement made (in Figure 1.1 the results always lie in an area marked with a Yes (or No)), then the fact that the economic data are less than perfect is irrelevant. Even in situations where the uncertainty is such that precise estimates on efficiency are not available, the nature of the decision-making context may help clarify the situation. For example, if the resource consequences (and the opportunity costs) of alternative courses of action are small (e.g. on row B of Figure 1.1) recommendations can be made on effectiveness alone. Results should be presented in a way that permits decision-makers to substitute local information or value judgements (Eccles et al., 1998).

An illustration of how these issues can be addressed in practice is provided by Mason et al. (1999), who considered a guideline recommending more appropriate use of ace inhibitors for heart failure in primary care. They showed that more appropriate use of ACE inhibitors may result in a gain in life expectancy of 0.203 years per patient and a reduction in cost of £206 per patient (area A1 in Figure 1.1). However, it was also possible that adopting the recommendation would result in an increase in costs of £1,578 per patient, which would result in an incremental cost per life year of £7,770 (area Cl in Figure 1.1). The difference in cost per patient was primarily caused by different estimates of the dosage of ace inhibitors required (British National Formulary, 1999) and of course dosage is an area where judgement is required. However, by quantifying both the extent and cause of the uncertainty around the estimates of cost-effectiveness, decision-makers can make an informed judgement.

A decision-maker needs to consider whether the economic evidence is sufficiently robust to be used in the context that it is required for, (i.e. are the data transferable?). This is of particular importance when economic appraisal is used to provide information as part of national guidelines. As with any study, the degree to which the results of an economic appraisal may be transferable from one location to another is crucial. This is influenced by the transferability of...