- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Party Change in Southern Europe

About this book

It has been argued that political parties are weakening. In Southern Europe, however, political parties have shown remarkable pragmatism. Not only have they played a crucial role in the installation and consolidation of democracy, mostly in the 1970s and 1980s, but they have also adapted to the aftermaths of severe political crises during the 1990s

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Party Change in Southern Europe by Anna Bosco,Leonardo Morlino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

What Changes in South European Parties? A Comparative Introduction

Anna Bosco & Leonardo Morlino

Party changes are a traditional topic of research and a major political issue within European democracies. Country-based studies and cross-national projects have explored the transformation of political parties and resulted in a number of empirical and theoretical contributions.1 In Southern Europe, however, political party changes have not gone hand in hand with comparative research. Hence, whereas during the last 15 years parties in Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece, Cyprus and Turkey have undergone a wide range of changes and innovations, these processes have not been the subject of systematic cross-national investigation. On the one hand, there are works that focus on single parties or countries, neglecting the comparative perspective. On the other hand, the small number of publications that have adopted a cross-national perspective (for example, Ignazi & Ysmal 1998; Morlino 1998; Bosco 2000; Diamandouros & Gunther 2001) cover in depth no more than the first half of the 1990s, with the sole exception of the most recent work by Van Biezen (2003) and Evans (2005) concerning Spain, Portugal and the Italian right-wing parties.

This research project has been set up to investigate whether and how political parties in Southern Europe changed between 1995 and 2005. The decade starting in the mid-1990s seems particularly relevant for the study of party change in Southern Europe, as shown by events such as the crossing of the government threshold by the right-wing Popular Party in Spain, the development of a system of coalitional bipolarism in Italy, the long opposition role played by the Portuguese and Greek conservative parties, the transformation of political Islam in Turkey and the consolidation of two different party systems in Cyprus.

For each country we decided to focus only on the two main parties. This decision is justified by the fact that we are not interested in small elite parties, where the role and choice of leaders are the prominent features, but in political parties with large electoral support that address the issues of membership, organization, identity, incumbency, as well as all the other aspects that are at the core of the present debate in the party literature (Krouwel 2006). As a consequence, we chose the two parties that by the mid-1990s were the main government and opposition forces in the South European countries.2 We were lucky enough to involve in the project a group of distinguished scholars who agreed to research the evolution of the selected parties. The articles that follow are the result of such an effort3.

As our interest is fundamentally empirical and comparative, we asked the au thors to follow a common framework of analysis based on four dimensions of party change: the values and programme, the organization, competitive strategy and campaign politics. The reason why we selected those aspects and not others (Gunther & Diamond 2003; Krouwel 2006) was that they represent the main dimensions (values, actors, rules and structures) along which a system can change. We were—and are—aware that each of these features could have become the subject of a whole book rather than a section of an article. However, by including all four dimensions, we chose to offer a broader picture of party developments. The authors of this special issue, in their contributions, analyse those aspects systematically in each party, so that the reader may trace the same dimension across all the parties.

At the end of the field research, with the written papers in our hands, the main empirical results to emphasize concern the survival of party membership, the role of party leaders, the current content of South European left- and right-wing parties in terms of values and programmes, and the balance of organizational power. These topics will be addressed in the next four sections, to be followed by a fifth concluding section on overall party changes (competitive strategy and campaign politics included).

Do Parties Still Enrol Members?

The data on party members collected by Mair and Van Biezen (2001) make clear that a lot has changed across Europe since the 1980s, as party membership has declined in almost every country.4 This decline has been explained by a variety of arguments, ranging from the insufficient 'supply' of members—due to political dealignment, generalized welfare state provisions and expanded education and leisure opportunities—to the weak 'demand' of party leaders and organizers, who seem to have found more efficient and less time-consuming ways to raise financial revenues, connect with the voters and mobilize electoral support (Scarrow 1996; Katz 2002).

How do South European parties fit into this picture of declining membership? Before answering the question, it is important to stress that the data we present here need to be viewed with caution. The articles in this issue report aggregate figures that refer to the total number of individual members claimed by each party. More often than not these data are inflated. As party leaders and officials consider the level of membership an indicator of legitimation to be used both outside (with the media) and inside the party (in internal battles), the tendency to 'adjust' the rolls is very common. Any researcher who has ever tried to get membership data from party officials, however, knows only too well that there is no way of checking the reliability of these figures. It is only when party leaders themselves decide to clean up the files that we can get more truthful information on the extent of their membership. In this context, two examples are in order. In Portugal the decision made by the new PSD leader, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, to clean up the membership files in 1996 resulted in a decrease of almost 60 per cent in the number of members. In Turkey the clientelistic tradition of the parties, the habit of local party officials of increasing the number of delegates they control by enrolling friends and relatives and the absence of any obligation on members to pay dues result in exceptionally large party memberships. As a consequence, when in 2000 CHP members were asked to reregister, the membership figure plummeted from almost two million to a meagre 170,000 (see Jalali et al., this issue). Notwithstanding these problems, we believe that membership data provided by parties may still be a reliable source to identify trends and a useful tool for comparative purposes.

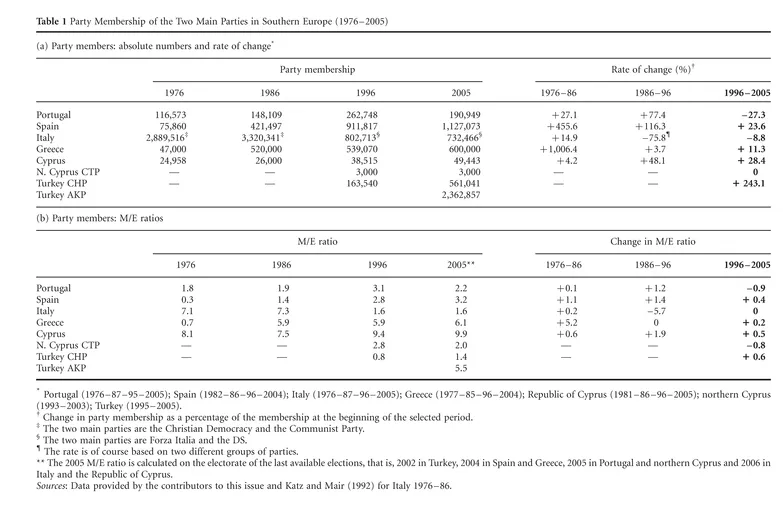

Table 1 presents the total number of members of the two main parties in each South European country over the 1976-2005 period and reports the same data as a percentage of the overall electorate (M/E or rate of organization), a measure that makes it possible to compare party memberships across nations and over time. The table also illustrates membership variation in each of the last three decades.

The trends in party membership show that today, in all but two countries, the main parties have more affiliates than ten years ago (Table 1 [a]). Only in Portugal and Italy is this not the case, while in northern Cyprus the number of party members has not changed. As for Turkey and northern Cyprus, however, we should stress that the data refer to only one of the two main parties: the AKP is a recent political force for which only the 2005 membership figure is available, while the northern Cypriot UBP does not have a register of party members (see Christophorou, this issue).

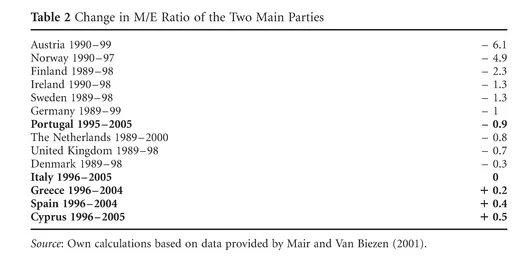

Such a picture of stability and growth with minor patches of decline is confirmed when we shift from raw numbers to the analysis of the rate of organization. The last column of Table 1(b) clearly shows that between 1996 and 2005 most of the party memberships not only kept pace with the growth of the electorate, but in four cases (Spain, Greece, the Republic of Cyprus and Turkey) even managed to grow at a higher rate than the national electorates. Only in Portugal and northern Cyprus is the M/E ratio negative, while in Italy the decrease in party affiliation was matched by that in the overall electorate, resulting in a zero rate. Therefore, a first conclusion that can be drawn from these data is that in Southern Europe there is no party membership decline as in the rest of Europe. In the 1996-2005 decade such a decline was limited to two countries, while even Italy seems to have stopped the haemorrhage of members that had characterized the general crisis of the early 1990s. Actually, if we compare the changes in the M/E ratio registered by the two main parties in a number of European polities between 1990 and 2000 with those recorded in Southern Europe, we identify different tendencies (Table 2).

When the rates of change registered in 1996-2005 are compared with those of the preceding 20 years another important aspect emerges very neatly, since this period

evinces a different trend in relation to the past. The last three columns of Table 1(a) and (b) show that four of the five countries for which data are available for the whole time span recorded a spectacular increase in the numbers of party members between the mid-1970s and the mid-1990s. Such an upward trend, however, becomes more moderate (in Spain, Greece and the Republic of Cyprus) or stops abruptly (in Portugal) by 1995-96. The dramatic growth of rank and file, related to the need to build party organization from scratch after the democratic transition, may have concentrated in the first decade, as in Greece and Spain, or in the second, as in Portugal, but since the mid-1990s it has slowed down or stopped altogether.

Italy, on the other hand, has followed the opposite pattern. After the sweeping changes of the parties and the party system in the first half of the 1990s (Morlino 1996), the main parties that emerged from that 'political big bang'—both new, as in the case of Berlusconi's FI, and old, as with the former communists renamed DS—have managed to keep the decrease in their rank and file below the threshold of ten per cent, putting an end to the deep membership decline of the preceding decade (Table 1[a]). A second conclusion, therefore, is that between 1996 and 2005 party memberships in Southern Europe have all distanced from their own past of exceptional growth or decline, becoming more similar to their other European counterparts.

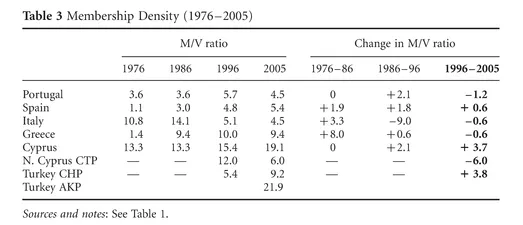

The data presented up to this point show whether political parties are successful in retaining their membership, but do not tell us anything about the quality of their efforts to enrol members. To complete the picture of the party rank and file we therefore now turn to the trends in membership density (M/V), a ratio calculated by dividing a party's membership by its own voters. Such a measure indicates 'a party's ability to penetrate its own electorate organizationally' (Poguntke 2002, 52) and can be used to gauge the different capabilities of the South European parties in encapsulating their electoral support.

When we consider the M/V ratio (Table 3), the picture of stability and moderate growth shown by the analysis of the rate of organization is not confirmed. On the

contrary, the South European main parties seem to have had difficulty in organizing the support of their voters: in four cases out of seven, a negative ratio is recorded for the 1996-2005 period.

Moreover, the data in the last column of Table 3 reinforce our contention that between 1996 and 2005 political parties in Southern Europe entered a different phase. On the one hand, Portugal, Spain, Greece and northern Cyprus record a membership density much lower than in the previous decades, signalling that parties are probably less motivated—and less able—to convert voters into members than in the past. On the other hand, again, the Italian case evinces a different pattern, as the political parties that consolidated their presence after the mid-1990s show a moderately negative membership density, similar to that displayed by the Greek parties—which did not have to face a political earthquake like the Italian one—a sign that the worst times are over. Overall, Table 3 sheds light on our third conclusion: parties are gradually losing their capacity to offer lukewarm supporters a more permanent organizational shelter, a trend shared with other Western European political forces (Poguntke 2002, 54-56).

Taken together, the data on party membership display a number of differences between the national cases, as well as among the parties. This leads us to the last question to be addressed: which parties are more able to build up and keep stable their membership over time? And, in particular, does the left-right divide make any difference in terms of membership organization? Table 4, which reorganizes, along the left-right split, the dat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- 1 What Changes in South European Parties? A Comparative Introduction

- 2 The Woes of Being in Opposition: The PSD since 1995

- 3 The Importance of Winning Office: The PS and the Struggle for Power

- 4 If It Isn't Broken, Don't Fix It: The Spanish Popular Party in Power

- 5 Turning the Page: Crisis and Transformation of the Spanish Socialist Party

- 6 Forza Italia: A Leader with a Party

- 7 The Democratici di Sinistra: In Search of a New Identity

- 8 From Opposition to Power: Greek Conservatism Reinvented

- 9 Party Change in Greece and the Vanguard Role of PASOK

- 10 Party Change and Development in Cyprus (1995-2005)

- 11 From Political Islam to Conservative Democracy: The Case of the Justice and Development Party in Turkey

- 12 Old Soldiers Never Die: The Republican People's Party of Turkey

- Notes on Contributors

- Index