![]()

1 Developing the Co-researcher INvolvement and Engagement in Dementia model (COINED)

A co-operative inquiry

Caroline Swarbrick and Open Doors

Outline

This chapter outlines the development of the CO-researcher INvolvement and Engagement in Dementia (COINED) model using co-operative inquiry. The consultation stages of the development of COINED are shared together with how people living with dementia want to be involved in research and the challenges and opportunities that this presents for academics and organisations. The COINED model could be seen as a guiding frame for the book in the applied use of creative and social research methods that follow.

Introduction

Since the early 1990s, researching the lived experience of dementia has seen the researcher role evolve from one of detachment – where the researcher had control over the design, data collection, transcription and analytic process – to one of inclusion where the person(s) living with dementia is seen as an integral member of the research team and the authentic voice in representing shared meanings. This changing face of dementia studies has been manifest in many ways and in this opening chapter we will focus on one such journey which underpins work programme 1 of the NIHR/ESRC funded ‘Neighbourhoods and Dementia: a mixed methods study’ (referred to henceforward as the ‘Neighbourhoods Study’) – a five-year research study (2014–2019) as part of the first Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia in the United Kingdom (UK) (Department of Health, 2012 and see Keady et al., 2014; www.neighbourhoodsanddementia.org). Work programme 1 of the Neighbourhoods Study is all about people living with dementia as co-researchers and meets two of the overall Study aims, namely: (i) to learn from the process and praxis of making people living with dementia and their care partners; and (ii) to build capacity within the research community and the networks of people living with dementia and their care partners.

However, in beginning to address such fundamental aims it is important to establish what roles and ambitions people living with dementia themselves see as important in conducting research. Working alongside three of the activist/peer support groups attached to the Neighbourhoods Study – the Open Doors project (based in Salford, Greater Manchester, UK; http://dementiavoices.org.uk/group/open-doors-project/), the Scottish Dementia Working Group (based in Glasgow, UK; www.sdwg.org.uk/) and EDUCATE (based in Stockport, UK; www.educatestockport.org.uk/) – this chapter outlines the development of an innovative, participatory model of research involvement and engagement, the CO-researcher INvolvement and Engagement in Dementia model, or COINED for short (Swarbrick et al., 2016). The development of the COINED model through the methodology of co-operative inquiry, and the shared vision and values that underpin it, represent the primary focus of this chapter, whilst also fostering the need to develop more creative social methods that promote full and participatory engagement of people living with dementia in research.

Co-research and co-operative inquiry

Whilst there are examples of generic ‘involvement in research’ frameworks, such as INVOLVE (www.invo.org.uk/), which is funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health Research, its transferability into the dementia research field remains under-developed. Within the UK, one of the principle areas to involve people living with dementia as co-researchers1 is in health service and social care provision, of which examples include service planning and design (Cantley et al., 2005; Eley, 2016), service development (Cantley et al., 2005; Litherland, 2014) and service evaluation (Cheston et al., 2000; Litherland, 2014). Contemporaneous with such developments, are an increasing number of influential dementia working groups and networks, regionally and internationally, that aim to drive forward an empowerment and activist agenda as well as inform policy; see, for example: European Working Group of People living with dementia (www.alzheimer-europe.org/Alzheimer-Europe/Who-we-are/European-Working-Group-of-People-with-Dementia); Irish Dementia Working Group (http://dementiavoices.org.uk/group/irish-dementia-working-group/); Ontario Dementia Advisory Group (www.odag.ca/); and the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (http://dementiavoices.org.uk/). As a further illustration, the involvement of people living with dementia through the medium of consultation has influenced dementia strategies at a local level (McCabe and Bradley, 2012) and a national level (Eley, 2016).

The implicit theoretical underpinnings of co-research are largely embedded within a co-operative inquiry methodology. Co-operative inquiry focuses on the lived experience, traditionally referred to as ‘experiential research’ (Heron, 1971). The purpose of co-operative inquiry is to develop mutually usable knowledge between contributors (Baldwin, 2001), particularly through innovative and creative practices with the emphasis on researching together (Reason, 1999; Heron and Reason, 2001). There are numerous examples of co-operative inquiry within wider health and social care fields, including mental health (Hummelvoll and Severinsson, 2005) and learning disabilities (Healy et al., 2015); however, it has received limited research attention in dementia studies (Swarbrick, 2015). The potential of co-created knowledge to have far-reaching impact makes its relevance to research in dementia studies significant, most notably through its creative and empowering underpinnings and its aim to close ‘the gap between research and everyday life’ (Heron and Reason, 2001, p. 182). Co-operative inquiry is framed around four ways of ‘knowing’, which we now describe through the lived experience of dementia:

1 ‘Experiential knowing’ relates to the experience of living with a diagnosis of dementia. Its inherent empathy and understanding particularly towards others who may also have a diagnosis is often represented through peer support.

2 ‘Presentational knowing’ concerns the visual representation of the lived experience, expressed through a range of creative approaches, which do not necessarily depend on the written word. Examples include art, poetry, music and dance. Whilst such creative approaches are often referred to as ‘interventions’ within clinical and academic contexts, here we refer to them as enjoyable activities undertaken in everyday life.

3 ‘Propositional knowing’ refers to the ‘science behind the knowing’, enabling us to make sense of our own experiences. It is the very essence of who we are, what we believe and how we understand and make sense of our world, and is embedded within our own life story.

4 ‘Practical knowing’ brings together the underpinnings of Experiential, Presentational and Propositional knowing, and is demonstrated through skill or competence. Changes in cognition (experienced during trajectory of dementia) will invariably shape the performance and level of the skill or competence and it is the responsibility of all contributors to recognise that such skills may be demonstrated through creative, ‘non-traditional’ means (Heron, 1996; Reason 1998, p. 427; 1999).

These types of knowing are integral to the four phases of reflection and action, which form the basis of co-operative inquiry. These four phases are built on an iterative cycle of human experience, focusing on the interplay between reflective processes and practical application. Each phase is traditionally informed by an Inquiry group/s and members, who are referred to in the remainder of this chapter as ‘Inquirers’.

Inquiry groups

The authors (Caroline Swarbrick – Facilitator; Open Doors – founding Inquiry group) worked alongside an additional two established groups of people living with dementia from the inception of the co-operative inquiry: EDUCATE and the Scottish Dementia Working Group. Due to geographical logistics, Open Doors, EDUCATE and the Scottish Dementia Working Group met independently, but the Facilitator remained constant throughout the Inquiry. Despite the formality of an ‘Inquiry group’, relationships remained informal, peer and friendship-based (Heron and Reason, 2001). Inquiry group meetings ranged from four-18 members and met a total of eight times. This process will now be described in more detail.

Focus of inquiry (phase 1 – reflection)

All three Inquiry groups were research active groups and using this as a starting point, initial discussions (as led by Open Doors) focused on the representation of people living with dementia in research. It soon became clear that the viewpoint and experiences of research were regarded as something ‘done to’ rather than ‘done alongside’ people. Whilst the desire of Inquirers to be part of the wider research process was clearly evident, they acknowledged that opportunities for involvement beyond the realms of participant were very limited (propositional knowing). There were many parallels across group discussions with regards to the focus of inquiry, with the consensus on exploring ways of involving people living with dementia across the research process as co-researchers (presentational knowing).

Involvement in research (phase 2 – action)

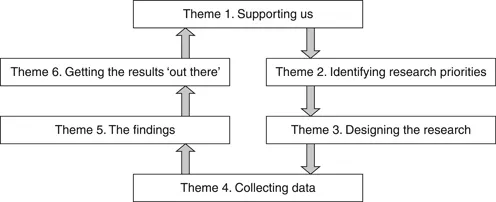

Building on the key messages of phase one, phase two sought to identify practical ways of involving and integrating people living with dementia as co-researchers within and across the research process. Here, Inquirers took an active role in exploring the ‘doings’ of research in a practical, discussion-based format (experiential knowing). Open Doors and the Scottish Dementia Working Group took part in wider group discussions, whilst EDUCATE engaged in smaller group work activities (due to the numbers of people involved). The purpose was to develop a single framework which would be used as the basis of co-researcher involvement. Ideas were interchanged between Inquiry groups via the Facilitator, who remained the consistent link between all groups for the duration of the co-operative inquiry. Despite working independently, there was consensus amongst Inquiry groups with six common themes emerging to develop an initial draft framework of involvement, which mirrored INVOLVE’s research cycle (INVOLVE, 2012, p. 40) (practical knowing). Inquirers were keen to use the initial ideas, as presented in Figure 1.1, as a platform to develop a more comprehensive model of involvement across the research process. In particular, Inquirers were also keen to identify specific areas of involvement with the aims of enriching the quality of the research process and integrating the lived experience within the dementia studies arena. Here, there was a natural progression into phase 3 of the co-operative inquiry.

Figure 1.1 Initial involvement framework.

Developing the model (phase 3 – action)

The rebalancing of control within the research process was acknowledged by Inquirers as an important step forward in the integration of people living with dementia across the trajectory of the research process. Building on the initial framework outlined in Figure 1.1, Inquirers developed a more descriptive anthology of approaches (see Figure 1.2), which were generated collectively over the three groups, as led by Open Doors. Inquirers’ understanding of the research process facilitated a shift from the initial stepped cyclical framework to an iterative pattern of action from an immersive approach (practical knowing).

Ongoing training and support

Inquirers unanimously agreed that ongoing training and support is fundamental to the involvement of people living with dementia as co-researchers. This works in two ways: first, training and support for people living with dementia as co-researchers; and second, training and support for academic researchers working alongside people livi...