eBook - ePub

Illegal Drug Use in the United Kingdom

Prevention, Treatment and Enforcement

- 249 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Illegal Drug Use in the United Kingdom

Prevention, Treatment and Enforcement

About this book

First published in 1999, Illegal Drug Use in the United Kingdom provides a comprehensive review of information and interventions available in drug misuse in order to inform local drug policies. In keeping with the policy documents in both Scotland and England, the volume covers the breadth of possible interventions, rather than health care alone. Separate chapters review educational, policing and counselling approaches and discuss work with special groups such as rural drug users, sex workers and club-goers. Although there are specialist textbooks on all aspects of addiction, this is the first text-book to bring together information in the framework used in the policy documents in the UK.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Illegal Drug Use in the United Kingdom by Cameron Stark,Brian A. Kidd,Roger A.D Sykes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

European drug policy on supply and demand reduction

Introduction

The problems of drug misuse and abuse are not new to Europe, neither are the solutions. Historically most western countries have followed the American approach to the ‘war on drugs’, with its emphasis on supply reduction and disruption in consumption.

Experience reveals that if there is a demand for prohibited drugs, then there is an opportunity for organised crime to make profit by supplying that demand. Those involved in the supply of illicit drugs will find ways to circumvent legal controls by resorting to bribery, corruption and violence, while the police and customs agencies are largely left to plug the holes. The international nature of the drug problem has necessitated international cooperation and action. Many Western European countries have examined their responses to illicit drug use. They have recognised that drug-related problems have multiple causes, and need multi-disciplinary responses built into properly resourced, planned and coordinated drug policies at local and European levels.

European responses to drug misuse

The creation of the European Community in 1957 provided the impetus and framework for developing and implementing European drug policies through a number of groups and European institutions. Two significant groups in relation to drug policy development were the former Trevi Group and CELAD.

The Trevi Group was set up by the European Council of Ministers in 1975, to provide a basis for greater European cooperation to combat terrorism. The initial brief was later expanded to tackle other organised crime such as drugs trafficking. Membership of the Trevi Group included representatives of each member state, plus others attending as observers. An early initiative was the development of a network of Drug Liaison Officers (DLOs) in drug producer and transit countries, and national drugs intelligence units in each member state - subsequently national intelligence units linked to the Europol Drugs Unit (see page 8).

CELAD was instigated in 1989 by President Mitterand of France, who wrote to the European Community heads of government and the President of the Commission, suggesting the establishment of a European Committee to Combat Drugs: CELAD. CELAD’s membership was made up of government-nominated representatives and the European Commission. CELAD prepared a programme of measures including a first European Action Plan, which was approved by the European Council in Dublin, 1990. The programme included five measures:

- Inter-member coordination

- A European Drugs Monitoring Centre

- Demand reduction

- Suppression of illicit drugs trade

- International action.

The subsequent integrated pan-European Plan, aimed to develop a programme of action at both Community and member state level, and included coordination of anti drug strategies in member states and suppression of illicit trade in drugs. The Programme includes measures intended to contribute towards the reduction in demand for drugs, and created a European Observatory on Drugs. The European Action Plan has been revised twice - in 1992 and 1994 - when CELAD held its most recent meeting. The Plan recognises that prevention must be given at least as much attention as the laws and penalties relating to drugs and drug trafficking. The latest European Action Plan, covering the years 1995 to 1998, is built on three elements:

- Prevention of drug dependency

- Reduction of drug trafficking

- Action at the international level.

European framework

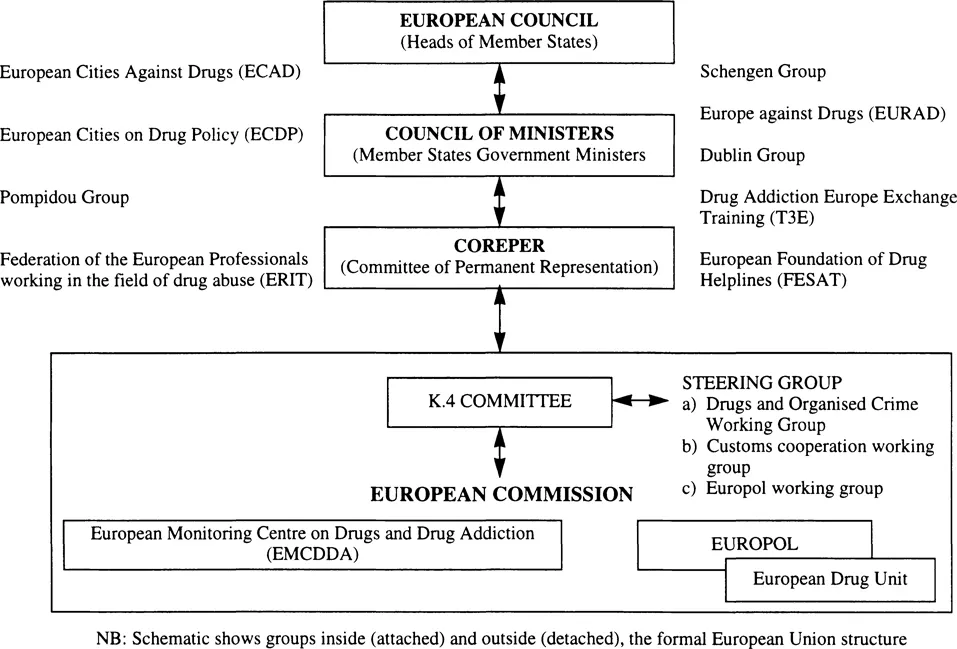

What follows is a brief description of drug-related organisations currently operating in Europe, both within and outside the formal framework of the European Union. Figure 1 provides a schematic description of organisations and their interrelationships, and page 14 lists useful contacts. The European Community, based on the Treaty of Rome signed in 1957 by six countries - Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands (the United Kingdom joined in 1973) - sets out the Community’s legal framework, providing flexibility and stability for close neighbours to work together to tackle common problems such as drugs.

The expansion and strengthening of the European Community was achieved through both the Single European Act (SEA) and the Treaty of European Union (TEU). SEA, established in 1986, created a European Community without internal frontiers, and expanded areas of competence into issues such as freedom of movement for people, services, goods and capital. The TEU was ratified in November 1993 and is commonly referred to as the Maastricht Treaty. It is dedicated to increasing economic integration and strengthening cooperation among its member states, and is a major expansion and amendment to the organisational framework of the Treaty of Rome. Decision making in the European Union is divided between supra-national European institutions and the governments of the member states, supported by the European Commission.

European Union and subsidiarity

Getting the right balance between European Union and national action on issues such as drugs is known as ‘subsidiarity’. The Maastricht Treaty provides a framework for governments to work together in key areas outside the tight rules of the Treaty of Rome. The Maastricht Treaty is founded on three pillars of cooperation under the European Council:

| Pillar I | Public Health and Trade Cooperation {based on the Treaty of Rome, Single European Act, Maastricht Treaty), where full community rules and procedures apply. |

| Pillar II | Common foreign and security policy (based on the Maastricht Treaty) where inter-governmental cooperation applies. |

| Pillar III | Justice and Home Affairs (based on the Maastricht Treaty), where inter-governmental cooperation applies between national governments and the European Commission. |

Figure 1.1 Drug-related organisations operating in Europe

Drugs are tackled by the European Union in two ways, under ‘community competence’, where Community institutions are empowered to act, and within the framework of the Union, by ‘cooperation between member states’.

Community competence

Under Pillar I, powers are conferred on the Community by European treaties which are no longer in the province of national decision-making. These powers are subject to the principle of subsidiarity, which stipulates that the Community shall take action only when and in so far as the objectives of a proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the member states. In relation to drugs, articles within Pillar I which have been used are:

- Articles 57 and 100A were the basis for the EU directive on preventing the use of the financial system for money laundering

- Article 113 allows the community to take steps to discourage the diversion of precursor chemicals for the illicit manufacture of drugs

- Article 129 relates to public health, and deals specifically with drug prevention

- Article 130W allows the European Community to work cooperatively with non-EU nations, in the field of drugs.

Cooperation between member states

Intergovernmental cooperation applies to Pillars II and Pillar III. Although Pillar II does not refer to drugs specifically, member states have joined together their diplomatic efforts to promote the European position: for example, in June 1993 the European Council recognised drugs as suitable for common action under the Common Foreign and Security Policy.

Pillar III, Title VI, Article K.l, is relevant to the drugs issue. Article K.l, provisions 7, 8 and 9, cover drug trafficking, and provision 4, drug prevention. All Pillar III work is supervised by the Justice and Home Affairs Council made up of government ministers of member states, supported by the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER), and a committee of senior officials known as the K.4 committee, who coordinate all activities. Working to K.4 are three steering groups covering immigration and asylum (Steering Group I), police and customs cooperation (Steering Group II), and judicial cooperation (Steering Group III), each with a number of specialist working groups; for example, the Drugs and Organised Crime Working Group, involves agencies/representatives from all member states, and reports to the European Council.

Subjects tackled by the Drugs and Organised Crime Working Group include production of an annual report on drug trafficking. They have reviewed a wide range of issues including drug trafficking in Latin countries, Turkey and the Central and Eastern European Countries; drug tourism; domestic cultivation and production of drugs; controlled deliveries; police/Customs agreements; money laundering; synthetic drugs; chemical profiling; exchange and secondment of law enforcement officers and undercover agents.

The Customs Cooperation Working Group involves customs personnel from all member states, and addresses drug-related issues including: improving external border control; control of container traffic; cooperation on controlled deliveries; trafficking on European routes; information exchange between member states’ DLOs and cross-border coordination between customs and law enforcement.

European institutions

The five most important institutions within the European Union are:

- The European Council, involving heads of state as well as the President of the European Commission. The European Council’s role is to set political priorities for the EU at its twice-yearly meetings

- The Council of Ministers is made up of ministers of heads of state, and concerned with the adoption of EU legislation

- The democratically elected European Parliament is primarily involved with influencing EU policy through consultation and cooperation

- A central function is provided by the European Commission, which makes draft legislation/policy suggestions, upholds the Treaties and manages the European Union’s international trade relationships

- The European Court of Justice serves as the final arbiter in matters of legal disputes among EU members and institutions.

In addition to the five primary European Union institutions, two new drug-related European institutions have been established: the European Monitoring Centre (EMCDDA), and the European Police Office (Europol).

EMCDDA was established in Lisbon in 1994, and provides the Community and its member states with objective, reliable and comparable European information concerning drugs, drug addiction and their consequences. It has five priority areas:

- Reduction of the demand for drugs

- National and community drug strategies and policies, including international, bilateral and community policies, action plans, legislation, activities and agreements

- International cooperation and geopolitics of supply (with special emphasis on cooperation programmes and information on producer and transit countries)

- Control of trade in narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and precursors

- And work on the drugs economy, particularly small- and medium-scale drug trafficking, and laundering of drug money.

Supporting the work of EMCDDA is a network of 15 National Focal Points set up across Europe, and one at the European Commission, within the European Information Network on Drugs and Drug Addiction (Reitox). Reitox facilitates and coordinates activities related to EMCDDA, and acts as a conduit to and from member states and the Monitoring Centre. The EMCDDA should add value to the available information and drug statistics by producing annual European-wide reports on drugs. The National Focal Points for the United Kingdom are based at the Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence (ISDD), which seeks to advance knowledge, understanding and policy making about drugs through research and by collecting and disseminating information, and the Department of Health, which is responsible for health promotion including drug prevention and treatment, and has a general brief for cross-government drugs publicity and information.

Europol was agreed in the Maastricht Treaty within Article K.3 (2c -provision of a convention), and Article K.l (9). Subsequently, the Europol convention was signed in 1995 by representatives of all member states’ governments, recommended for adoption within their respective constitutional requirements, and the way cleared for ratification by the European Council in June 1996 (UK has ratified the Europol convention). The base for Europol is The Hague. The Europol convention aims to ‘improve police cooperation in the field of terrorism, unlawful drug trafficking and other serious forms of international crime through constant confidential and intensive exchange of information between Europol and member states’ national units’. These forms of bilateral and multilateral cooperation are not affected by the Treaty. Principle tasks which Europol undertakes are to:

- Facilitate exchange of information between member states

- Notify the competent authorities within member states of information pertinent to them and criminal offences

- Aid investigations in member states by provision of relevant information to the national units

- Disseminate good practice in investigative procedures

- Provide an EU wide central and operational analysis

- Be a centre of excellence

- Give technical and linguistic support.

The Europol Drugs Unit (EDU) has been established within Europol since 1994, and is functional within The Hague. It is staffed by police and customs officers from member states of the European Union. The EDU is not an operational unit rather concentrating on criminal intelligence gathering on drug trafficking and money laundering. Intelligence is share...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- 1 European drug policy on supply and demand reduction

- 2 UK policy

- 3 Education and drug misuse: school interventions

- 4 Operational policing issues

- 5 Counselling for drug misuse

- 6 Medical interventions

- 7 Residential rehabilitation services

- 8 Drug services in rural areas

- 9 Working with women who use drugs

- 10 The treatment of drug users in prison

- 11 Recreational drug use and the club scene

- 12 Sex workers

- 13 Co-morbidity

- 14 Issues in assessing the nature and extent of local drug misuse

- 15 Creating a local strategy

- Index