![]()

1The UK regional–national economic problem

1.1 Introduction to the UK regional–national economic problem

The UK is a deeply uneven country on two broad dimensions, namely the geographic dimension and the governance dimension. The effects of modern globalisation, and in particular the links between automation, out-sourcing, off-shoring and the ‘hollowing out’ of many middle-skills jobs, mean that while globally we have observed a broad international convergence between countries’ incomes, within advanced economies we increasingly observe a greater polarisation and divergence of incomes (Bourguignon 2015; Atkinson 2015a, 2015b; Galbraith 2012). In other words falling inequalities internationally are widely associated with increasing intra-national inequalities (McCann 2008; Goos et al. 2009; Iammarino and McCann 2013). However, intra-national inequalities also challenge good governance (Galbraith 2012; Berg 2015). Yet, the extent to which these inequalities are also both geographical and regional in nature is almost unique in the case of the UK. In most other advanced economies these changing employment, skills and income distributions are dispersed much more evenly across the country, whereas in the UK they appear to be more heavily biased towards certain regions than in almost any other advanced economy. Moreover, although they pre-dated the 2008 global financial crisis by several decades, these divergence trends have accelerated in the years immediately before and after (Williams 2011) the crisis. Being characterised by these long-standing interregional divergence processes the economic geography of the UK nowadays increasingly reflects the patterns typically observed in developing or former-transition economies rather than in other advanced economies. As we will see in this book, these interregional inequalities also challenge good governance.

As well as interregional inequalities part of the reason is that the UK also simultaneously exhibits one of the most highly centralised governance systems in the industrialised world (Cheshire et al. 2014; Coy 2014; RSA 2014; HoC 2014; Adonis 2014; RSA 2015; Diamond and Carr-West 2015). After more than 70 years of increasing centralisation (Diamond and Carr-West 2015)1 central government in London rather than sub-national government dominates almost all arenas of policy-design, policy-making and policy interventions to a scale that is almost unknown elsewhere amongst the advanced economies. According to the UK Prime Minister David Cameron “This country has been too London-centric for far too long”2 and

Over the last century Britain has become one of the most centralised countries in the developed world … I am convinced that if we have more local discretion – more decisions made and money spent at the local level – we’ll get better outcomes.3

and largely the same point is made by the previous UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown throughout his recent book (Brown 2014) and by the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne.4 At the same time, however, the UK has an also varied and increasingly unequal regional governance system which in many ways is completely out of step with the economic geography realities of today’s UK economy and which works well neither in theory nor in practice. A governance system which in the past appeared to be reasonably well-suited to responding to both national and regional challenges now appears to be increasingly incapable of such responses, in some sense reflecting the regional divergences and in other senses exaggerating them (Bogdanor 2015a).

It is this stark mismatch between the UK’s interregional economic geography and the UK’s regional governance system that is at the heart of the UK’s regional economic problem. Moreover, the scale of this misalignment between the economic geography and the governance system is now so great that most simple policy, academic and constitutional ‘solutions’ offered as remedies for resolving the “over-centralised state and the south-centric economy that are two of Britain’s biggest problems”5 wholly fail to address the fundamental nature of the problem, which is the combination of these two problems.

In order to understand why this mismatch is such a fundamental problem there are two major features that we need to be aware of, namely the role of interregional inequality, and the role of appropriate governance systems, in the functioning and performance of a modern economy. These complex issues are discussed in great detail in the various chapters of this book, but at this stage we can highlight the broad outlines of some key themes central to the overall arguments in the book.

In terms of income inequality, there is now a growing body of evidence emerging from very high-level sources such as the IMF and OECD which demonstrates that growth in internal income inequality is not beneficial for long-run national economic growth (Berg and Ostry 2011; OECD 2014a, 2015a; The Economist 2014a) and neither is inequality beneficial for urban (Royuela et al. 2014) or regional (de Dominicis 2014) economic growth.6 In particular, in the case of the UK the adverse effects of growing income inequality since the 1980s on the economy’s long-run performance since 1990 have been the third worst in the OECD (OECD 2014a). Whereas previous growth models tended to focus almost entirely on aggregate productivity growth with little concern for distributional issues, nowadays environmental sustainability and social cohesion are increasingly understood as being essential elements for ensuring strong growth in the long term. In particular, greater income inequality limits the opportunities and thereby inhibits the ability of the lower middle classes to engage and participate in growth-enhancing activities such as education and entrepreneurship, and this subsequently reduces social mobility (OECD 2014a). While higher social class households are largely unaffected by rising income inequality its adverse impacts are felt almost entirely by the lower 40 per cent of the income spectrum, and these adverse impacts on such a broad group reduce the long-run lost potential of the economy (OECD 2014a). At the same time, there is no evidence that redistributive measures promoting access to skills-training, education and welfare via taxes and transfers hamper long-run growth, as these provide social investments for enhancing and widening opportunities.

The awareness that growth is a more multi-dimensional phenomenon than was appreciated in the past has been emerging over the last decade (Stiglitz et al. 2009). Indeed, this shift in thinking towards a more multi-dimensional understanding of growth and development reflects something of a worldwide shift away from the more narrow and largely sectoral approaches popular in previous decades which tended to focus almost entirely on investments in human, physical and research capital with little regard for social or environmental sustainability. These new and broader lines of international7 thinking which pre-dated the 2008 global financial crisis (Stiglitz 2002; Krugman 2003, Porrit 2005) have of course also been bolstered by the painful experience of the 2008 global economic crisis (Roubini and Mihm 2010) and subsequently have underpinned a range of very high-level international reports and commissions examining the nature of growth and development (Stiglitz et al. 2009; OECD 2009a; World Bank 2008, 2010a, 2010b). As with previous research, these shifts in thinking have not produced a simple and complete analysis of growth. Rather, what these shifts in thinking all share is a growing consensus that successful long-term development needs to be environmentally aware,8 broad-based and socially inclusive (World Bank 2008, 2010a, 2010b; NIC 2012; OECD-Ford Foundation 2014) in order to be long-lasting (OECD 2014a, 2015a; Berg and Ostry 2011; Ezcurra 2007; The Economist 2014a; Florida 2010; Sachs 2011; Stiglitz 2012, 2015; Piketty 2014), and rising income inequality (Stiglitz 2012; Piketty 2014) is evidence that the current growth trajectory is moving against these desired societal trends (Dorling 2011).

From a policy perspective, these shifts in thinking also imply that in order to be effective policies must be built on a broadly based political consensus. In other words, as well as enhancing economic drivers modern policy approaches to growth and development must also connect with the broader dimensions of social and environmental sustainability, because each of these features plays an important role in fostering the economic, social and civic engagement aspects underpinning the different dimensions of wellbeing (OECD 2011a).9 As a result, recent policy frameworks such as the 2009 OECD “Global Standard” growth strategy (OECD 2009a) of ‘stronger, cleaner and fairer growth’,10 the Europe 2020 Strategy of ‘smart, sustainable and inclusive’ growth (European Commission 2010), and the US growth strategy of ‘sustainable communities, innovation clusters, revitalizing neighborhoods’11 all aim to better translate these dimensions into a broader agenda and framework for policy-makers. Yet, changing policy frameworks are themselves unlikely to solve these problems in the near future, and in reality reflect a changing set of emphases and priorities for current and future decision-making. In contrast, today’s internal domestic income inequality is a result of complex social, economic and historical forces as well as political decisions taken over many previous years regarding the role, the scale and the use of the state’s fiscal resources. As has also been mentioned above, over recent years the forces of modern globalisation are also increasingly influencing internal income disparities in many different countries. For our purposes here, however, an important observation is that internal national income inequality is also associated with interregional inequality.

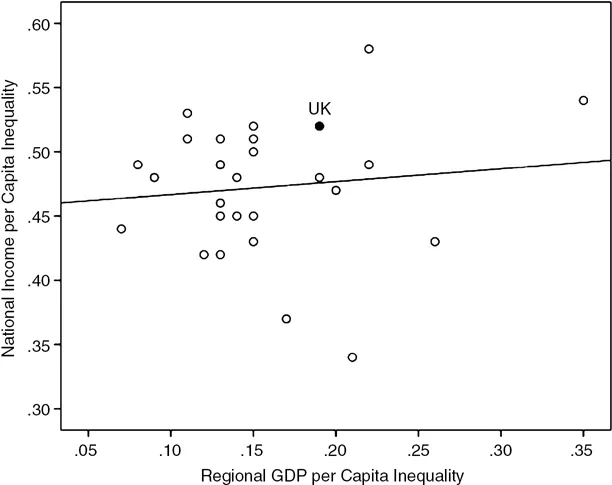

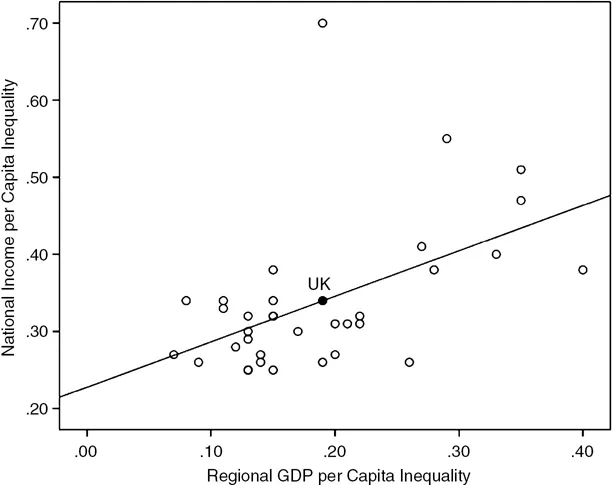

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 show the scatterplots across the OECD and BRIICS12 countries in 2010 of the relationships between the Gini index of interregional GDP per capita – calculated at the OECD-TL3 level – and the Gini index of domestic income inequality, prior to and post taxes and transfers, respectively. In general countries in the lower left part of the scatterplots exhibit low income inequality and low interregional inequality in GDP per capita while those in the upper right hand part of the scatterplots exhibit high income inequality and high interregional inequality in GDP per capita. Countries in the lower right hand part of the scatterplots exhibit high interregional inequality in GDP per capita but low income inequality while those in the upper left part of the scatterplots exhibit high national income inequality but low interregional inequality in GDP per capita.

As we see from Figure 1.1 and 1.2 there is a correlation between the level of national interregional inequalities in GDP per capita and also the national levels of income inequality, measured either before or after taxes and transfers. We know that the differences between the pre and post transfers and taxes inequalities are a result of the extent to which the national tax systems are redistributive, and across the OECD these systems differ significantly. Yet, even allowing for these differences, the general pattern remains clear that interregional inequality in GDP per capita is associated with higher national income inequality. As such, some levels of income inequality appear to be largely independent of spatial or regional issues, while higher levels of inequality do appear to be related to spatial, geographical and regional issues.

In both cases the position of the UK in the scatterplots is significant. In each of the two scatterplots the UK is at the upper right extreme of the scatterplot of the rich OECD countries with only one of the countries to the right of the UK exhibiting a higher GDP per capita than the UK. All of the other countries to the right of the UK are poorer countries than the UK, compr...