- 532 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume provides the first comprehensive history of education and training for officers of the Royal Navy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It covers the development of educational provision, from the first 1702 Order in Council appointing schoolmasters to serve in operational warships, to the laying of the foundation stone of the pre

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Educating the Royal Navy by Harry W. Dickinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du 19ème siècle. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire du 19ème siècle1

ALL AT SEA

The naval schoolmaster 1702–1837

The notion of an organised officer entry into the Royal Navy – the identification of candidates, a selection process, some form of initial assessment of ability both mental and physical, a structured pattern of training and education towards an identifiable end state – what we understand in the modern context as a ‘system’, may first be identified in embryo in the second half of the seventeenth century. Successive wars against European powers, the French, the Spanish and particularly the three Anglo Dutch Wars fought over more than two decades from 1652, provided a stimulus to manpower reorganisation and reform within the British Navy. During the Commonwealth there was a massive increase in the size of the fleet with more than two hundred vessels added to the 40 or so available at the end of the Civil War. The vigorous ship building programme stimulated and required improvements in pay and conditions of those who manned them and a more methodical approach to the employment of both officers and men. The intermittent periods of peace were equally problematic for they demonstrated the need not only to recruit, but also to retain manpower, in order that those who had demonstrated skill and professionalism in the previous conflict might be employed quickly and effectively in the next. It is in how officers and men were recruited and retained, and how they were encouraged to regard what they were doing as something permanent and professional, that the inklings of a system of training can be found.

In the Commonwealth era it had been traditional for warships to be manned and commanded by professional seamen, ‘tarpaulins’ who either assumed their position by rising through the ranks in government service at sea, or had been drafted from command of merchant vessels.1 These were invariably experienced seafarers, competent in navigation and sail handling but rough of habit and often of dubious loyalty. When Charles II returned to the throne he and his brother James, the Lord High Admiral, attempted to encourage a different class of officer more versed in the ways of the court and drawn from the nobility and gentry. The definition of these two groups, the ‘gentlemen’ and the ‘tarpaulins’, was an arbitrary one, for aristocrats had served the republic and equally there were ‘gentlemen officers’ who had some merchant ship experience. Nevertheless it is a useful classification because, as one commentator has noted, it was how contemporary figures, particularly Samuel Pepys, clerk of the acts of the Navy Board and secretary to the Admiralty, perceived sea officers.2 The concept thus underpinned attempts to achieve a unified and professional officer corps. In the 1670s Pepys and his royal masters attempted to deal with a range of personnel problems at sea and ashore ranging from the formalising of ‘seniority’, a crucial step in defining how officers should behave towards each other and how they should be advanced, to more pastoral matters including the formal establishment of a naval chaplaincy. The limits of service were addressed with regulations introduced for both the retirement of senior officers and a qualifying examination for those starting their careers. Not all these measures were successful and some of them had unintended consequences but they do provide a very general datum point for the formation of the modern naval officer corps.

Thanks in part to this reform process, by 1700 there were broadly three methods of entering the Royal Navy as a commissioned officer.3 The age old avenue of becoming a servant to a captain or an Admiral was still much in evidence. From the earliest of times there were youngsters borne on ship’s books to absorb and learn the practices of the sea. Just as on shore a nobleman took a page, or a city guild provided an apprenticeship, so officers took boys to sea and became providers of a sort of social and vocational training. By the start of the eighteenth century this process had become formalised and a scale of numbers established. A rear admiral was allowed 15 servants; a captain could employ four servants per hundred men by complement and a lieutenant and a midshipman one servant each, although the system was much abused. At this point most aspirants to professional sea service fell into this category. The second entry avenue was as a Volunteer per Order or ‘King’s Letter Boy’, a direct product of Pepys’s efforts to regulate and improve the quality of entrants and in particular to combat the incidence of well bred but incompetent candidates cluttering the junior ranks. Volunteers had to conform to certain age limits and have served a minimum time at sea before they could be considered for promotion. The significance of this type of entrant was that he was an Admiralty nominee, in possession of the ‘King’s Letter’ and therefore to be taken and trained whether the particular captain liked it or not. The third route to commissioned status was via service as a rating, invariably as a midshipman. Confusingly there were a number of different types of midshipmen and the title could be applied to any one of the three types of entrant. A servant could be rated as such, because captains still retained this prerogative, but a Volunteer could also be a midshipman if he had completed his two years’ qualifying time. The title was also reserved for the highly experienced lower deck rating, seasoned in navigation and seamanship, harbouring ambitions to walk the quarterdeck.

The administrative device providing the common hurdle to be cleared before further career progress could be made was the examination for lieutenant and if the evolution of naval education and training has a defined starting point, it is located with this measure. It was sponsored by Pepys and published in a Royal Proclamation on 22 December 1677.4 The test demanded a competence in seamanship and navigation and that every candidate be at least 20 years old and have served a minimum three years at sea before he could be considered. There were also requirements for sobriety, diligence and obedience. Certificates of competence were to be obtained from three senior officers of whom one was to be a flag officer or the captain of a first or second rate ship. The examination was designed to impose minimum levels of competence and combat what Pepys described as a widespread general incompetence and dullness in ship’s junior officers, of which he noted ‘all sober commanders at this day complain’.5 It was also an important bureaucratic device and by the end of March 1678 Pepys was claiming success not only in raising standards but also in controlling numbers, noting that ‘we have not half the throng of those of the bastard breed pressing for employment … they being conscious of their inability to pass this examination’.6

Despite Pepys faith in the regulatory qualities of the examination it is unlikely to have been completely successful for there is some evidence that undeserving candidates still received commissions and the secretary constantly complained, rightly or wrongly, of ‘the ruinous consequences of an over-hasty admitting persons to the office and charge of seamen upon the bare consideration of their being gentlemen’.7 Nevertheless the introduction of a formal test prior to advancement was a vital step and while we cannot know how many were deterred from presenting themselves, we do know that some of those who did found it a trial. Success was not guaranteed and there are examples of officers applying to be reexamined before boards who questioned them on navigation, tidal problems, seamanship and sail handling. Even experienced sea officers could be caught out, with Pepys noting that one candidate who had spent considerable time afloat and had been given all the requisite information, was still unable to predict the time of the tide at London Bridge. He was advised to return to his ship and reapply at a later date.8

Most commentators have seen the introduction of the lieutenant’s exam as a vital measure in improving the overall competence of officers and it is curious that the decision to examine was not complemented by a similar one to instruct, indeed it was a further 25 years before the Admiralty wedded the two concepts. Nevertheless the measure seems to have sparked some unofficial teaching in warships conducted either by existing members of the crew or by sea going teachers recruited for the purpose. Trinity House records, for example, show that at least two men, James Nicholson and Henry Knight, were employed as teachers in the warships King’s Fisher and Dorsetshire respectively, prior to 1700 and there were almost certainly others.9 The other source of unofficial instruction and preparation for the lieutenant’s exam were teachers in the private mathematical and navigational schools variously located on the banks of the River Thames, but particularly at Blackwall, Greenwich and Wapping. Young officers attended schools between voyages and the tutors were often former ship’s masters, river pilots or surveyors who published textbooks and plans of learning based on much practical experience. Among the more well known were Peter Perkins, a former master at Christ’s Hospital Mathematical School who published The Seaman’s Tutor in 1682, and Mathew Norwood who in 1685 wrote Systems of Navigation. Perhaps the best known teacher of the era was Samuel Sturmy whose Mariner’s Magazine was first published in 1679, and ran to four editions.10

The decision to carry out instruction at sea, to take the teacher to the pupil rather than the other way around, has been variously attributed. One commentator has noted Admiralty concern for standards of navigational competence brought home by the wreck of HMS Association, which, together with Eagle and Romney, struck rocks off the Scilly Islands on the night of 27 October 1707.11 This resulted in great loss of life including that of the commander Sir Cloudesley Shovell, who made it to shore, but was reputedly killed by looters. Yet while this episode undoubtedly demonstrated the difficulties of navigating in poor visibility and heavy weather, it cannot have influenced the decision to send instructors to sea for this had been in operation for more than five years by this point. It has also been suggested that the appointment of naval schoolmasters might have been prompted by John Arbuthnot’s book, published in 1700, in which the author claimed to have seen a superior system of education in France, where by order of the King professors were appointed to teach navigation in all major seaports.12 Again this seems tenuous, for instruction was already in evidence in London, via both the private tutor system and more formal foundations such as the Royal Mathematical School at Christ’s Hospital. This school was founded in 1673, specifically to teach mathematics and navigation to 40 pupils, who stayed at school until the age of 21 and were then examined by Trinity House. Some of the earliest applicants for naval schoolmaster posts were former pupils of Christ’s Hospital.

Clearly shoreside instruction in navigation was a somewhat different concept to teaching theory and practice on board ship. Pepys, a governor of Christ’s Hospital, was well aware of the limitations of the school room and noted in his Tangier Journal that teaching boys solely before they went to sea ‘will never do the business it is designed for’. The problem he felt was that the officers on board the King’s ships were ‘very ignorant themselves’, or at least ‘careless of the boys keeping their knowledge’.13 This theme was expanded upon by serving sea officer Lieutenant Edward Harrison, who in 1696 published Idea Longitudinis, one of a number of contemporary works that wrestled with the overwhelming navigational problem of the era, the accurate determination of longitude. In the preface to his work, Harrison bemoaned the lack of training for sea officers and in particular the fact that mathematics teachers seldom went to sea for that purpose. The result he claimed was that ‘most of their scholars when they come to sea are half to begin again’.14 Whether this was the stimulus to official action is unclear but there is little doubt that it was the situation the Admiralty sought to address. In an Order in Council of 21 April 1702 it was announced that £20 per year would be added to a midshipman’s pay and given to anyone willing to go to sea and undertake the duties of schoolmaster. The task was limited but specific – to instruct young gentlemen ‘not only in the theory but the practical part of Navigation’ and to ‘instruct the Youth in the Art of Seamanship’.15 Vacancies were to be created in ships of the third, fourth and fifth rate and captains were warned to accept only those who could show they were of sober background and conversation and who could produce a certificate proving they had been examined and found competent by Trinity House of Deptford.16

This requirement for external examination and validation was not unusual and applied to a number of warrant officers in the Restoration Navy. From 1665 chaplains, who had originally joined ships by local arrangement, required the authorisation of the Archbishop of Canterbury and subsequently the Bishop of London. Surgeons were examined by the Barber Surgeons Company, although this system seems to have worked less well.17 In matters of seamanship and navigation the Corporation of Trinity House was a natural choice, for they had examined and reexamined ship’s masters from 1621 and extending the process to those who would teach basic mathematics and navigation at sea was a simple task. The prospect of £20 plus a midshipman’s pay produced results and a steady stream of prospective instructors presented themselves for examination – one estimate suggests that between mid May 1702 and the end of August three years later, some 62 certificates of competence were awarded to naval schoolmasters.18

The sea going teacher seems to have escaped further official attention for almost 30 years for there is no official mention of the post until the issue of the first Regulations and Instructions relating to his Majesties Service at Sea issued in 1731. These directions were one of a series of reforms introduced between 1727 and 1733 that included improvements in seaman’s pay, overhaul of charities and the foundation of a naval academy in Portsmouth dockyard. More specifically the Regulations sought to bring commanding officers, particularly those of ships in distant waters, under close administrative and financial control and were probably an attempt by the Admiralty and its Deputy Secretary, Thomas Corbett, to see that captains did their job properly.19 To this end all members of the ship’s hierarchy, the lieutenant, the master, the purser, the chaplain and so on, had their duties identified and laid down in a series of articles. The duties of the schoolmaster, and by this

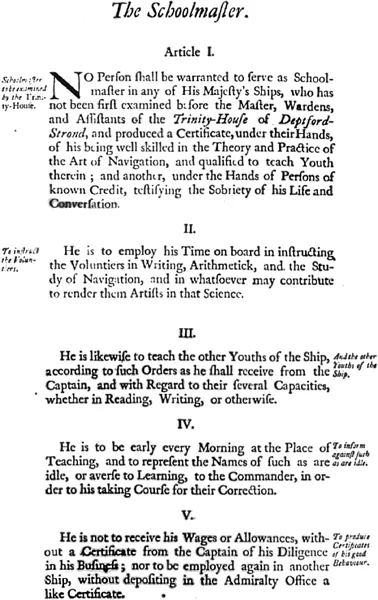

Figure 1 ‘Duties of the Naval Schoolmaster’ – an extract from the 1731 Regulations and Instructions. (Author’s collection)

stage he is specifically referred to as such, were broadly similar to those outlined in the original 1702 Order. Listed between the ship’s corporal and the cook, the schoolmaster was to be ‘early every morning at the Place of Teaching and to represent the Names of such as are idle or averse to Learning to the commander’.20 This stipulation may have reflected a need for some increased status for the ship’s teacher, who was only rated and paid as a midshipman and shared his living quarters, yet had no formal authority. The requirement to instruct the young officers in arithmetic and navigation originally identified in the 1702 Order was repeated, although the duties were now extended to include reading and writing, not only for the young gentlemen, but also for the other youths of the ship.

The remaining articles of the 1731 Regulations provided further definition of the schoolmaster’s duties. He was to produce the usual certificates of competence from Trinity House but was now required to show a second certificate ‘under the Hands of Persons of known Credit testifying the Sobriety of his Life and Conversation’.21 The authorities seem to have been suspicious of their schoolmaster applicants, for an examination of these and later Regulations, shows him ...

Table of contents

- CASS SERIES: NAVAL POLICY AND HISTORY

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 ALL AT SEA

- 2 ‘A SINK OF ABOMINATION …’

- 3 PITCHFORKS AND PROFESSORS

- 4 INKLINGS OF A SYSTEM

- 5 BRITANNIA AT DARTMOUTH, 1863–74

- 6 ‘WHILE THEIR MINDS ARE DOCILE AND PLASTIC …’

- 7 ‘AS MUCH BY WISDOM AS BY WAR …’

- 8 THE FORTUNES OF HMS BRITANNIA 1874–1902

- 9 ‘ENGINEERS ARE NOT GENTLEMEN …’

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- SOURCES

- INDEX