Grzegorz W. Kolodko

1. Introduction

To believe is the privilege of politicians. Economiste should know. The economie policy makers - who are typically economiste put in charge of politics - usurp the prerogatives of both groups and mistake belief for knowledge. What they believe is that, the way the world is made, the poor should be able to catch up with the rich and reduce the enormous differences in the level of economie development. Yet, these differences somehow grow year by year. Today nearly half of the world’s inhabitants live on less than two dollars a day, and a billion people - a sixth of mankind - subsist on less than a dollar.

Faith, of course, can help, but knowledge is of decisive importance. What then do we know about the capacity of the emerging, relatively backward market economies to catch up with the highly developed countries? What systemic arrangemente and development strategies might lead to this objective? What historic lessons are there to be learned concerning the management of economie growth in the future? How to distinguish the inevitable legacy of the past, which can only evolve in time, from the economie policy options left open? These are the questions that should constantly be addressed, ali the more so since the old answers become outdated as the development factors change.

A third of a century ago, in 1969, the United Nations set up an expert group, known as Pearson Panel, to suggest measures facilitating growth in less developed countries and to level out the differences in living standards. Guided by belief, rather than knowledge, the Panel proposed development strategies which supposedly promised the backward countries (many of which were then in the process of gaining independence after centuries of colonialism) to attain a 6-percent growth over the coming decades. Countries that managed thus to accelerate their economie growth were expected to become - mainly through the expansion of exports - self-reliant partners in the world economy by the year 2000.

The year 2000 has passed. And it turns out that the course of development outlined by the Pearson Panel is a rare exception rather than a rule. The United Nations established, therefore, a new expert group, this time headed by the former President Ernesto Zedillo of Mexico, whose task is to advise on policies aiming to foster economie catching-up and, in particular, to implement the ambitious goals put on the agenda by the UN Millennium Summit - one of which was to reduce the number of people living in extreme poverty by at least half a billion until 2015. The Zedillo Panel believes that this could be achieved through rapid economie development, if only the rich countries would increase their annual assistance for poor countries to 0.44 per cent of their GDP. The trouble is, as we ali know, that they would not (although they should) and so development aid lags at a paltry 0.22 per cent. Consequently, the numbers of the poor do not shrink, disparities in development level increase, and distances to catch up grow. The year 2015 will soon have passed, too, conceivably, without bringing any noticeable improvement. There will be few winners, many more losers, and ali the remaining actors are also likely to be dissatisfied with the way the globalized economy operates and the living standards achieved. Can we do better than that?

This paper deals with the fundamental theoretical aspeets of and practical prerequisites to the catching-up process in the emerging market economies. Foliowing this introduction, Part 2 presents the hitherto efforts in this area and the actual socio-economie processes going on over the last decades. Part 3 describes the current phase of globalization and analyzes its influence on the trends in output change and its pace. Part 4 contains a characterization of the young, institutionally immature market economies which seek to boost their growth rate through integration with the global system. The disparities in development level between various countries and regions in the world economy are discussed in Part 5, along with their implications for the catching-up process. Finally, Part 6 is devoted to the policies of systemic reform and to conclusions concerning a desirable development strategy to foster fast, sustained growth in the emerging market economies.

2. Back to the Future

The past is gone. And so is the present, because in reality it does not exist, every passing moment turning instantly and irrevocably into the past. Thus ali that is left is the future. Which is the most important thing. However, to be able to couch our expectations about the future in rational terms, we need a good understanding of the past. Otherwise, we will never manage to forecast future development processes with reasonable accuracy, or to actively shape these processes (which is even more important). For the socio-economie aspeets of the future are not only the function of time and some chaotic development processes, but, first and foremost, depend on a conscious development strategy combined with a growth and distribution policy.

Throughout history, only about 30 nations, with a total population of less than a billion - that is, about 15 per cent of mankind - has managed to attain a relatively high development level, with GDP per head exceeding USD 15,000 in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP).1 Outside North America and Western Europe, this group comprises the member countries of the OECD from the Asia and Pacific region - Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand - as well as Singapore. This level has also been achieved by some oil-exporting OPEC countries (Brunei, Kuwait and Qatar), certain economies with special structural characteristics (like the Bahamas, Martinique and Taiwan), and a few overseas territories of highly developed countries (like French Polynesia or New Caledonia). In 2001, the highest-income group was joint by the first and only post-socialist country thus far - the tiny (2 million inhabitants) Slovenia.2 Next in line is the Czech Republic, where GDP per head is expected to exceed USD 15,000 in 2004.3

On the other extreme are countries unable to overcome the vicious circle of poverty. Some of them not only fail to dose the staggering gap that separates them from highly developed countries, but keep plunging in stagnation and recession, lagging further and further behind not only economically, but also culturally. It happened in the past, and it happens, occasionally, today (Magarinos and Sercovich 2001). No doubt it will also happen in the future. Why? The answer is that only few countries in history managed to catch the train of progress. It was only possible if three favorable circumstances co-occurred.

First, economie development always requires technological progress. Without the spread of new manufacturing methods and the implementation of novel technologies that change the organization of production, no innovation is possible - and it is innovation that drives economie growth. Necessary - but not sufficient -conditions of technological progress also include, obviously, high-quality human capital, an adequate level of education and science, as well as efficient system arrangements in these areas (Kwiatkowski 2001).

Second, in order to sustain long-term development trends, it is essential to reform the institutional framework of an efficient market economy. Otherwise, even a relative technological superiority is no guarantee of rapid economie growth, as creative enterprise becomes stifled in such circumstances.4 Obviously, creative enterprise is even less possible in technologically backward countries. Thus, without the capacity for economie reform, rapid output growth can hardly be relied on.

Third, a creative feedback between technological progress and economie reform calls for politicai determination on the part of the politicai elites, who must be willing to upset the existing balance and to challenge the established position of conservative interest groups. Only then can the ‘new’ gain the upper hand of the ‘old’, which is necessary for a sustained productivity growth. The fear of the temporary confusion that accompanies this kind of change often paralyzes the authorities, who then begin - through their reluctance to stimulate and institute the required reforms - to hamper rather than facilitate economie progress and socio-economie development.5

One needs to reminisce about the past - including more distant past, spanning several centuries - if for nothing else, then in order to realize, at the outset of a new millennium, that history is happening at ali times. Now, too, because of the three momentous processes coinciding today: the current phase of permanent globalization (Bordo, Eichengreen, Irwin 1999; Frankel 2001; Kolodko 2002a), the post-socialist transformation (Blanchard 1997; Lavigne 1999; Kolodko 2000a), and the modem scientific and technological revolution (Raymond 1999; OECD 2000; Payson 2000; Kolodko 2001d). It is in this context that we should perceive modem developments, so as to avoid missing the train of progress once again. Not everyone succeeded in this task in the past: actually, few did. The same thing is being repeated now: some will get on the train, some will be left waiting, and some might even get pushed off the platform.

Incidentally, this phenomenon has abeady been observed for two decades. This is shown, for instance, by a World Bank report (World Bank 2002a) which distinguishes - apart from the rich economies6 - two main groups of states. Today the terra ‘developing countries’ is less frequently used with reference to these, for the simple reason that some of them are hardly developing. Instead, one speaks about more globalized countries (MGC) and less globalized countries (LGC). This distinction is based on the participation in the intemational labor division, measured by the dynamics of foreign trade. A third part of the countries where the growth of the proportion of foreign trade volume to GDP in the 1980s and 1990s was steepest has been classified as MGCs, and the remaining two thirds as LGCs.7

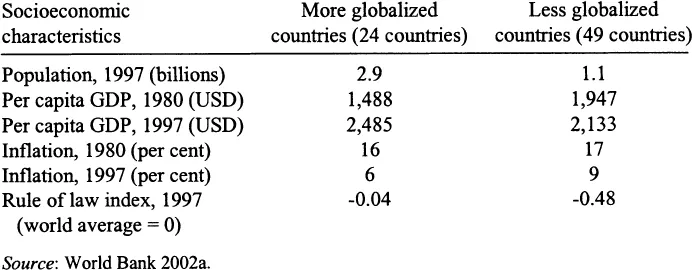

The group of 24 countries which become more actively involved in the world economy (MGCs) has a total population of nearly 3 billion. The 49 countries less tightly integrated through foreign trade with the world system (LGCs) have about 1.1 billion inhabitants. The circumstances of the two groups differ widely, and changes in output level and dynamics, as well as the living standards, follow different trends in either group (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Characteristics of more and less globalized countries

In 1980, GDP per head (in PPP terms) in the MGC group stood, on average, at less than USD 1,500; by 1997, it increased to nearly USD 2,500 - that is, by almost two thirds. In the LGC group, the increase amounted merely to about USD 200, or less than 10 per cent. Taking into account just the last five years, the respective proportions become even more striking. While the MGCs have kept developing at an average rate of about 5 per cent annually and managed to further increase GDP per head by almost USD 400, reaching about USD 3,100 in 2002, the LGCs have recorded an about 6-percent drop in GDP per head, to about USD 1,900 in 2002. Thus the difference in this respect changed from about USD 500 in favor of the LGCs in 1980 to about USD 1200 in favor of the MGCs in 2002. These are significant qualitative differences which alter the face of the modem world.

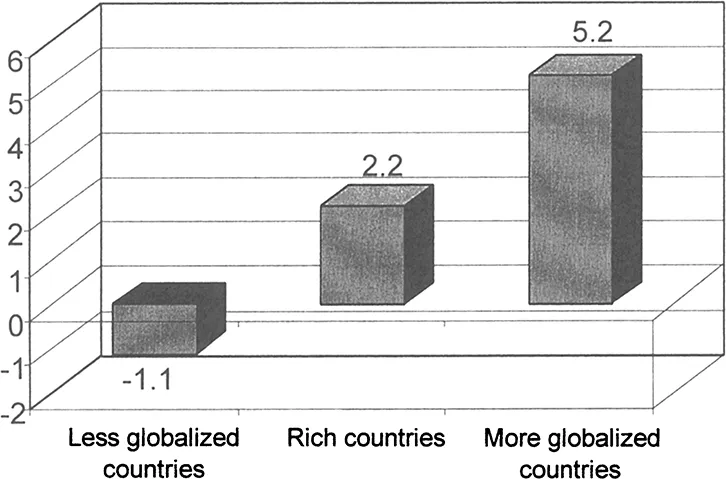

Such tendencies indicate that within the time span of a single generation, the economies that take more active part in globalization managed to double their real income per head. Unfortunately, the income of other societies, less involved in the development of international trade, did not increase, on average, at ali. If a shorter time span is taken into account, and these processes are viewed solely from the perspective of the 1990s, we will see a 63-percent increase of GDP per head in the MGC group8 and a drop by about 10 per cent in the LGC group9 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Economie growth in the world economy, 1991-2000 (GDP per head in per cent)

Source: Dollar and Kraay 2001.

However, one must not overlook in this context the fact that this general, fairly encouraging picture of change results mainly from the unprecedented progress attained by just two countries. But these were quite special countries, too: China and India, inhabited jointly by some 2.3 billion people. Therefore, their growth rate has an overwhelming impact on the indicators of the entire MGC group.

It is an important and noteworthy fact that both China and India - although they follow different routes and their progressive integration with the world economy and involvement in the worldwide competition likewise takes dissimilar paths -pursue development strategies by no means based on the neoliberal orthodoxy and the classical prescriptions that stem from the so-called Washington Consensus,10 which has been invoked so often recently in mainstream economies and figured prominently in the recommendations given to many countries by the G-7 countries, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Both China and India are reforming their respective economies at their own, not too quick pace, but with a great deal of consistency and determination. They liberalize capital movements gradually and with moderation, while the exchange rates are effectively controlied by the state at ali times. Moreover, their monetary policy is subordinated to the overall national policy, the top priority of which is rapid economie growth. To this end, state intervention is used in both countries more extensively than elsewhere, mainly in the forni of industriai and trade policies. Such a combination of structural reform and development policy brings favorable results.11

Chinese GDP increased in the 1980s by as much as 162 per cent, which amounts to an average real year-to-year growth of 10.1 per cent. In the 1990s, growth was even faster, reaching 10.7 per cent annually, to produce a cumulative output increase of another 176 per cent. In 2000-2002, growth rate has somewhat declined, fluctuating around 7 per cent. Thus over the past 23 years - within the time span of a single generation - GDP in China has grown by a staggering 780 per cent! Giv...