- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The shots fired during the early morning hours of February 3, 1989, at the Asuncion headquarters of the presidential escort battalion presented the planet with its first blood-and-steel evidence that the year would be recorded, like 1848, as one of universal human liberation. The deposed government of Alfredo Stroessner had held power in Paraguay for close to 35 years, a political longevity then surpassed only by Bulgaria's Todor Zhivkov, North Korea's Kim ll-song, and Jordan's King Hussein.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paraguay by Riordan Roett,Richard S Sacks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

International Relations1

Introduction

The waters of the Upper Paraná alone are said to equal those of all European rivers.… As for the Paraguay, from its source, As Sete Lagoas (The Seven Lagoons) in the central sierra of South America, to this confluence it flows some 1,200 miles; from here to the sea another 950….

The forest—this has happened suddenly—has become jungle. Temperature has risen, there is a change in vegetation, which is thicker, brilliantly lit by flowers, white, violet, scarlet. At the rim of this dark violent chaos lie huge rotting trees, half in, half out of the muddy water. The choking confusion of vegetation, the thickset trees, lianas, creepers are seen to be components of a wall; its very impenetrability excites one to try it.

—Gordon Meyer, The River and the People

On February 3, 1989, Paraguay emerged from almost thirty-five years of one-man rule—a modern record for Latin America—when a rival general overthrew General Alfredo Stroessner in a bloody coup. The general who overthrew Stroessner, Andrés Rodríguez, was one of Stroessner’s closest associates. Rodríguez had invested much personal capital in Stroessner’s regime and had benefited unabashedly from his rule. As this book was being written, Rodríguez had become the constitutional president of the republic. He was elected three months after the coup to fill out the term of his predecessor, just as Stroessner had been elected in 1954 to fill out the term of the deposed Federico Chaves.

With the most dubious of credentials as a democrat, Rodríguez nonetheless claimed to be putting the Paraguayan republic on the road to democratic government, vowing to step down when his term expires in 1993. Newspapers that Stroessner had banned were again on the streets. Many leading figures of the regime’s last years were behind bars or cleaning out cavalry stables. For the first time in history, mayors were about to be chosen by local, direct election instead of being appointed by the central power of the state.

Most important, Paraguayans were universally relieved that Stroessner was gone and were beginning to lose their fear of the police. Although Rodríguez is accused by many of being involved in drug trafficking in earlier years, he nonetheless promised to wage a crusade against the drug lords, whose influence was spreading everywhere in South America during the 1980s. As the man who got rid of an increasingly odious dictatorship, Rodríguez was enjoying a prolonged political honeymoon. Paraguay, under Rodríguez, was finally getting ready to enter the political twentieth century.

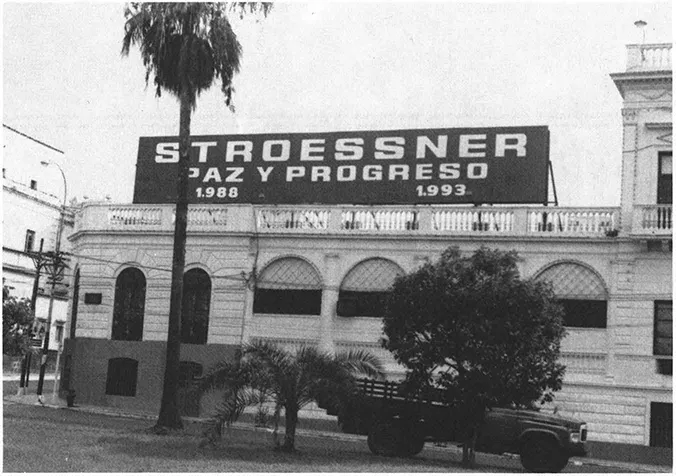

One of Stroessner’s ubiquitous signs. Most of these signs disappeared within days of the February 3, 1989, coup.

As president of a country that had never had a democratic system, Rodríguez was saying and doing some unusual things during his first year in power. But there is little about Paraguay that is not extraordinary. Paraguay’s population of 4 million is probably the most homogeneous on the continent, both racially and culturally. Unlike some of its neighbors, Paraguay has no racially based caste system: Virtually every Paraguayan is of mestizo ancestry. Nearly all Paraguayans speak the same language; their common national tongue is not Spanish but Guaraní, an Indian language. No other Western country affords an indigenous language such wide currency.

Paraguay is paradoxical. The first independent nation in South America, it has been one of the least free. The country never has had what Westerners would call a “clean” election; it has been run by dictators almost continuously since the Spaniards left. Approximately the size of California, the country is completely landlocked, yet it is a regional trading capital. Paraguay is nearly devoid of valuable natural resources with one exception: The world’s largest electricity-producing dam, Itaipú, is located on the Paraguay-Brazil border. Another huge dam, with one-quarter Itaipú’s capacity, is scheduled for completion by 1995 at Yacyretá, on the Argentine frontier.

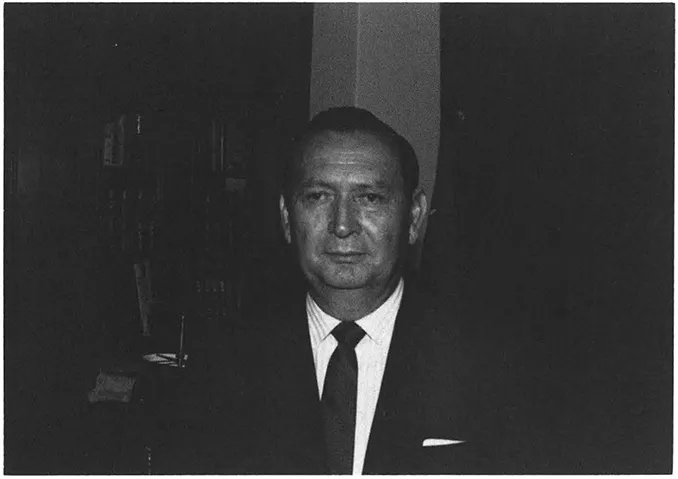

President Andrés Rodríguez before a Monday, February 6, 1989, news conference, three days after he seized power from President Alfredo Stroessner.

There is no compelling reason that Paraguay did not become an exotic but remote province of Argentina or Brazil. The country’s sixteenth-century birth was accidental: A handful of Spanish adventurers who had survived a brutal passage in their quest for gold found no riches, only a poor, godforsaken place at the ends of the earth. Paraguay became, for a short time, the focal point of Spanish colonial ambitions in southern South America, until would-be immigrants began to shun the colony for its lack of exploitable wealth. Under colonial rule, Paraguay was one of the least accessible places in the world. It soon became little more than a buffer province that the relentlessly expanding Portuguese in Brazil never ceased nibbling at.

Sometime during the eighteenth century, Paraguay became a place where time stood still; it was rural, poor, fearfully hot during most of the year, and almost as isolated and inaccessible as Tibet. Only now is it starting to emerge from this state. The tradition—or better, the habit—of personalist rule that began in colonial times has not yet died out in Paraguay. Independent institutions that may reflect independent thinking and produce independent agendas have never flourished. Attempts at independent action or thought have always inconvenienced those who monopolized state power. Whether ruled by Spaniards, dictators, or civilian or military oligarchs, Paraguayans never were asked their opinion about how they should be governed. Decisions are made, traditionally, not by consensus but by the man at the top.

The dictatorial tradition has done nothing to impede Paraguayan nationalism. Paraguayans have often been called on to defend their nation on the battlefield, and they have not shirked from the task. Independence was won when Paraguayan arms defeated an Argentine invasion. Paraguay underwent two major wars after independence. The first, the Triple Alliance War (1864–1870), was a holocaust that halved Paraguay’s population, leaving only one-tenth of the original male population alive. The second was the Chaco War (1932–1935) against Bolivia, which killed 80,000 soldiers on both sides but left Paraguay in possession of most of the contested area. Paraguay has proved that it possesses a national cohesion that is unrivaled in Latin America.

For such a small, out-of-the-way place, Paraguay has always attracted attention, if not notoriety, from abroad. In Candide, Voltaire took a gibe at the Jesuits in Paraguay who, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with the blessing of the Spanish kings, had organized at least 100,000 Indians on communal settlements far from the control of the colonial governor. Thomas Carlyle and Richard Burton, both English writers of the nineteenth century, recognized Paraguay as a bizarre place that reveled in its isolation and oddities by building a “Chinese wall” around itself. Indeed, from about 1816 until 1840, Paraguay resembled a “mousetrap”: No one was permitted to leave. Paraguayans who left were not allowed to return. Even foreigners who entered were forced to stay.

Although Paraguay achieved independence from Spain early, in 1811, the dictators who held power until 1870 were virtual kings who called themselves presidents. Paraguayans have been conditioned to follow; their leaders have gotten used to wielding absolute power. This habit was reinforced after 1947, when a brutal civil war prostrated the country, exiled a third of the population, and paved the way for the Stroessner dictatorship. With the overthrow of Stroessner in 1989, Paraguay was only just beginning to adopt the political practices of twentieth-century multiparty democracies.

Predictably, Paraguay’s dictators (Higínio Morínigo and Alfredo Stroessner, in particular) have felt attracted to people of like mind. In Asunción in 1989, one could still walk along a street named for Francisco Franco or view a statue of Anastasio Somoza García, the Nicaraguan dictator. Ironically, Somoza’s dictator son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was blasted to pieces by Argentinian guerrillas in Stroessner’s capital shortly after fleeing Nicaragua’s revolutionary forces in 1979.1 Jozef Mengele, the Auschwitz concentration camp doctor known as the “Angel of Death” for, among other things, his hideous experiments on 1,500 sets of twins, was issued a Paraguayan passport sometime in 1960. He was rumored to have worked briefly as a physician in the Chaco region2 before moving to Brazil, where he drowned in 1985.

Even if we assume that Rodríguez’s intentions are good, there are still limits to what he can accomplish easily, given Paraguay’s past. The slowness of the regime in bringing corrupt officials and torturers to trial indicates that the Colorado party-military-government ménage upon which the presidency rests will not tolerate any threats to its existence. Some internal dispute within the Colorado party or between the Colorado party and the military, as yet unforeseen, may cause the current alignment to disintegrate. What would replace it is unclear. Order has been a precious commodity in Paraguay, where pacific regime changes are unknown. Paraguay could easily descend again into the chaos that characterized the 1948–1954 period, when Asunción (Paraguay’s capital) was a no-man’s land and then-Colonel Alfredo Stroessner once arrived at the Brazilian Em...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Paraguayan History, 1524–1904

- 3 Modern Paraguayan History: The Twentieth Century

- 4 The Paraguayan Economy

- 5 Culture and Society

- 6 Politics and Government

- 7 International Relations

- List of Acronyms

- Selected Bibliography

- Index