![]()

1 The Small Firm as a Purchaser

Introduction

Although large firms are well suited to serving as the institution through which employees purchase benefits, small firms encounter difficulties in carrying out this role. Size enables large firms to reduce or eliminate two of the key problems that emerge as small firms attempt to cover their employees: risk variability, which results in extensive underwriting and associated high measurement costs in small firms, and lack of economies of scale. The objective of this analysis is twofold: first, to lay out the differences between small firms and large firms in their ability to effectively govern the health insurance transaction; and second, to assess mechanisms that can improve the performance of small firms. The mechanisms under consideration here are market rules and purchasing cooperatives.

As long as insurance is voluntary, there will always be some firms of all sizes that choose not to purchase coverage for their employees. Universal coverage, or even significant expansion of coverage, is unlikely without some form of compulsion. However, taking the private, voluntary, employment-based insurance system as given, reorganization of the small group market may improve its functioning for those firms interested in providing health care coverage.

Oliver Williamson’s “discriminating alignment hypothesis,” which forms the core of transaction cost economics, presents a conceptual lens for understanding the comparative advantages of different organizational forms in managing transactions: “transactions, which differ in their attributes, are aligned with governance structures, which differ in their cost and competence, so as to effect a discriminating — mainly, transaction cost economizing — result” (Williamson 1994 p. 14).1,2 In this case, the transaction — purchase of health care coverage — does not vary, but the governance structures at issue here — large and small firms — differ substantially in their ability to manage the transaction. Thus, the focus is on delineating the “cost and competence” of governance structures with respect to the health insurance transaction.

Because small firms are less competent governance structures, mechanisms are more likely to arise to improve their performance than to aid large firms. Further, mechanisms differ in their performance-enhancing potential for small firms. Thus, the key objective is to perform a comparative analysis of alternative governance structures for the health insurance transaction.3 Recognizing the difficulties associated with measuring transaction costs, Williamson emphasizes the comparative nature of the analysis: “[measurement] difficulties are significantly relieved by posing the issue of governance comparatively — whence the costs of one mode of governance are always examined in relation to alternative feasible modes” (Williamson 1994 p. 4).

Economists have tended to overemphasize the ability of prices to achieve efficiency in the health insurance market, and have endorsed “actuarial fairness” — premiums that reflect individual-level risk as fully as possible — to avoid incentive distortion (Cochrane 1995; Pauly 1970; Pupp 1981). Researchers from other disciplines have tended to perceive the proper function of health insurance as the redistribution of wealth from the healthy to the sick, advocating a single premium regardless of risk level — “moral fairness” — over risk-adjusted premiums (Daniels 1990; Stone 1993). This analysis takes neither of those paths. Instead, alternative modes of organizing the health insurance transaction are explored with neither a strict efficiency nor a redistributive agenda. Governance structures that economize on transaction costs or otherwise address costly features of the health insurance transaction are favored.

To establish a foundation for the firm as a governance structure for the health insurance transaction, section 2 traces the development of the theoretical connection between variability and the market arrangements that arise to economize on costly information expenditures. Section 3 differentiates between small and large firms in their ability to govern the health insurance transaction in a low-cost fashion. Section 4 briefly departs from employment-based health insurance to consider a neoclassical alternative. Section 5 returns to the firm as a governance structure, and considers market rules and purchasing cooperatives as mechanisms to improve the small firm’s ability to purchase health insurance. Sections 6 and 7 compare the mechanisms, and evaluate implications that emerge from the analysis. Section 8 presents a case study of one state’s approach to small-firm health insurance purchasing.

Variability, Information Asymmetry, and Differentiation

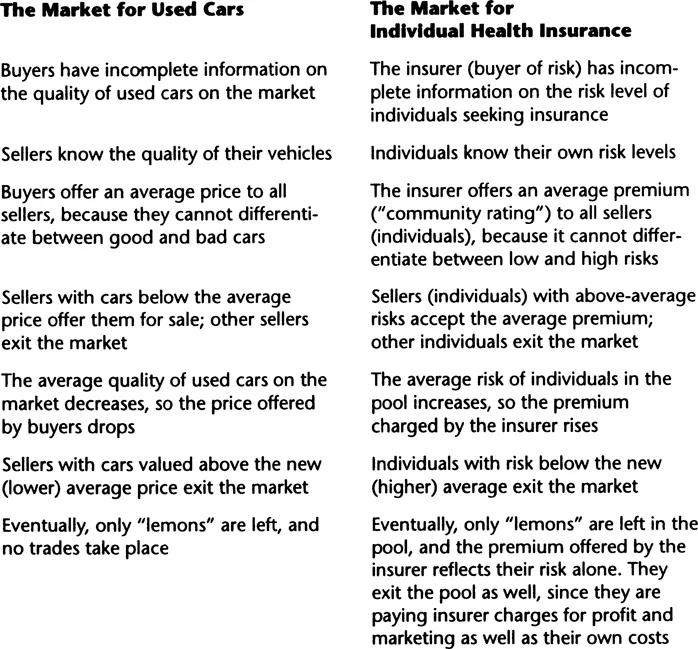

George Akerlof initiated discussion about the interaction between variability and asymmetric information with his 1970 paper on the used-car market. When sellers, but not buyers, can differentiate between items of varying quality, fewer (or no) trades will take place compared to the situation in which quality is obvious to both parties. This is because buyers, unable to differentiate, will offer average price for any given item. At that price, sellers with a high-quality item will be unwilling to sell and will exit the market. The average quality of the remaining items will now be lower, as will the price buyers are willing to offer. Again, the sellers with the highest-quality items among those remaining will be unwilling to sell. In the limit, only the “lemons” are left, and no trades will take place. As Table 1.1 demonstrates, Akerlof’s classic example is analogous to the health insurance market. In the used-car market, the product is the used car, and uncertainty relates to the quality of the used car; in the health insurance market, the product is the risk level of the individual, and uncertainty relates to that risk level (not to the insurance policy itself).

But according to these scenarios, no used cars or health insurance policies would ever be traded. Since we know that both commodities are commonly exchanged, how do we reconcile this seemingly plausible story with real life? One approach is to note that although the quality of a used car and the risk of an individual may not be immediately obvious or observable, neither are they necessarily unknowable. Thus, buyers or sellers or both can spend resources to differentiate between “lemons” and “non-lemons” or between high risks and low risks. Such expenditures make information more symmetric and allow price to reflect extant variability.

Michael Spence (1973) developed the idea that, when they can gain from doing so, individuals will spend resources to differentiate themselves from others or from the average. Spence’s model is as follows. Individuals will be paid for services in the labor market on the basis of average productivity even though they differ, because differentiating them is too costly for employers. The higher-productivity individuals will spend resources on higher education to differentiate themselves from the lower-productivity individuals, thereby earning higher-than-average wages. Their gain represents a loss to the other individuals, who now receive lower-than-average wages.4

TABLE 1.1 Used Cars and Hìgh-RIsk Individuals: Adverse Selection and “Lemons”

Spence assumes that screening by the employer is more costly than signaling by the potential employee, so the latter takes place. But some employers spend significant resources to differentiate among prospective employees during intensive application and interview periods. Signaling by the potential employee and screening by the employer both allow price (wage) to more closely reflect variable productivity among employees. Likewise, incurring costs to differentiate between “lemons” and “non-lemons” used-car market and high and low risks in the health insurance market prevents the markets from unraveling by reducing the cross-subsidization that can result in market exit of the non-lemons and low risks. The result, if variability is fully differentiated, is that each car sells for its quality-adjusted value and that each insured pays the cost of his or her expected risk (plus loading fee) in premiums.

In the presence of quality variability and asymmetric information, spending resources on differentiation — up to the limit of cost-effectiveness — is relatively efficient, compared to allowing the market to unravel. But differentiation involves measurement costs, sometimes high costs. Yoram Barzel (1977) introduced the idea that constraints on differentiation expenditures can have economizing effects:

Consider some people whose expected medical expenses are identical. Medical insurance, then, is sold to them at a uniform premium. With the progress of science, it is suddenly discovered that these expenses vary systematically across individuals. In a Spence-type world, we would now expect individuals who know that they are healthier to spend resources to convince insurance companies that they qualify for lower premiums.... The decline in premiums to healthier individuals will be accompanied by increases to all others. A redistribution of income from the sickly to the healthy, then, takes place at a positive resource cost (p. 302).

Barzel goes on to assert that, in spite of the potential for healthy individuals to gain at the expense of the sick, medical insurance is sometimes offered to groups (employees, union members, students). “A major feature of group health insurance is that no medical examination is required; individuals qualify simply by belonging to the group. Thus, a major sorting expense is bypassed” (p. 303). Barzel suggests that the reason that healthy individuals remain in the pooled group and submit to cross-subsidy to the sick is that eliminating the sorting expense that would otherwise be incurred creates substantial savings, such that purchasing inside the pool is less costly than purchasing outside the pool in spite of the cross-subsidy.

Building on Barzel, Roy Kenney and Benjamin Klein (1983) present three cases in which market mechanisms have emerged to prevent the costs that would have accompanied extensive differentiation: diamond sales by DeBeers, the distribution of motion pictures by Paramount and other major studios, and the sale of film rights to television. In each case, the seller set an average price for a product of heterogeneous quality (diamonds, films for theater, and films for television), and constrained the buyers’ ability to spend resources to differentiate the highest-quality items from those of average and below-average quality. The outcome was significantly reduced buyer search and seller measurement costs.

Once one begins to look for differentiation costs and mechanisms to reduce such costs, they appear on all sides. In the used-car market, differentiation costs come in the form of paying a mechanic to check on the prospective purchase, an extensive array of publications (the most familiar of which is the “Blue Book”), and services that provide detailed estimates on the value of the car, given specific information on mileage and other relevant parameters (e.g., whether the car has power windows). Mechanisms to reduce differentiation costs include dealer-issued warranties that are less comprehensive than those for new cars but that still provide a significant degree of protection, and trading among friends and relatives (Barzel 1977). In the health insurance market, differentiation costs might include medical history questionnaires, physical exams, and laboratory tests; as noted by Barzel, one of the most important mechanisms to reduce underwriting costs is purchasing health insurance through a group.

Group-based insurance is prevalent in the United States, covering trade associations, unions, and especially firms. Employment-based insurance covers the vast majority of the insured under-65 population (Silverman et al. 1995).5 To be sure, there are a number of reasons for the prevalence of employment-based insurance, including history and the tax code. A tradition of employment-based health insurance began during the World War II wage freeze; employers substituted fringe benefits, including health insurance, for prohibited wage increases. One powerful impetus for continuing the practice today is that insurance premiums paid by employers are tax deductible. But employment-based insurance would not likely endure without some cost-economizing feature of the sort observed by Barzel. The next section considers the firm as a governance structure for the health insurance transaction.

The Firm as a Governance Structure for the Health Insurance Transaction

Barzel’s posited grouping mechanism for economizing on the health insurance transaction incorporates two assumptions, one explicitly and one implicitly. First, as asserted by Barzel, the well or low-risk members of the group must subsidize the sick or high-risk members. Second, Barzel implicitly assumes that the risk level of the group as a whole is sufficiently predictable to allow the insurer to forego assessment of individual members. Risk of individual group members can vary as long as the group as a whole presents a predictable risk profile, which depends on the size of the group. Costly differentiation can take place on either side of the transaction: Healthy group members can distinguish themselves from the sick to obtain lower premiums, insurers can individually screen the members of prospective groups, or both types of activities can occur. Some degree of economizing on the transaction can occur if either or both sides consent to reduce differentiation activities. Consider each side in turn.

Why do low-risk employees consent to redistribution to high-risk employees? Perhaps the most important reason is that employers most often offer employees a choice between health benefits and no health benefits, not between health benefits and some other benefit or additional take-home pay. Some employers do offer such “cafeteria” packages, but they are in the minority.6 Thus, low-risk employees can e...