- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Unique in its coverage of such an extensive range of methods, Neuroscience Methods: A Guide for Advanced Students provides easy-to-understand descriptions of the many different techniques that are currently being used to study the brain at the molecular and cellular levels. This valuable reference text will help rescue undergraduate and postgraduate students from continuing bewilderment at the methods sections of current neuroscience publications.

Topics covered include in vivo and in vitro preparations, electrophysiological, histochemical, hybridization and genetic techniques, measurement of cellular ion concentrations, methods of drug application, production of antibodies, expression systems, and neural grafting.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

SECTION 1

IN VITRO PREPARATIONS

CHAPTER 1

SLICES OF BRAIN TISSUE

Institute of Neuroinfomatics ETH/Uni, Switzerland

INTRODUCTION

The brain slice technique was first applied to metabolic studies of small tissue sections as early as 1920. With the advent of the microelectrode technique at the beginning of the 1950s it was possible to characterize the resting membrane potentials of cells contained in freshly sliced tissue and compare them to brain cells in situ. It was soon realized that such slices provided new routes for the study of synaptic phenomena. Towards the end of the 1960s the use of surviving, metabolically maintained tissues from the brain for electrophysiological and pharmacological studies was becoming an accepted, valued and widely applied technique. But it was not until the advent of the whole-cell recording technique in the mid 1980s and its application to sections of brain tissue that the brain slice technique became very popular.

Brain slices weighing some 10 mg can provide access to fine structures and thus allows functional analysis of parts of the brain. Isolates of this size comprise some 104 to 105 cells. A large cerebral neuron may synapse with 103 to 105 other cells. Thus the cell pool provided in a brain slice may be the minimum unit size needed for adequate display of the connectivity of a cerebral neuron in its adult environment. Despite the trauma of their formation, adequately prepared slices approach the status of biological entities.

However, it is unrealistic to consider sliced tissue to be ‘normal’, no matter how skilfully and carefully the slices have been prepared. Slices are isolated tissue, without normal inputs, immersed in an artificial environment. Investigators must weigh the potential advantages with the obvious disadvantages as they apply to their particular problem. Advantages of the slice are: visibility, technical accessibility, stability and ease of use. Disadvantages are: loss of normal input pathways, shearing of dendritic processes and axons, tissue debris around the cutting surface mixed with healthy cells, slow release of cellular enzymes and ions from damaged cells, and altered metabolic state.

Depending on the experimental needs several variants of the technique have been developed and are being used. One distinction between the variants relates to how thick the slices have been cut. The thin slice technique was developed to allow visualization of individual cells in slices of less than 250μ m while the thick slice technique is used in experiments where connectivity and maintenance of normal dendritic structure are crucial for the study. Once prepared, slices can be kept alive in various media for hours or weeks. Ultimately slices can be kept in culture.

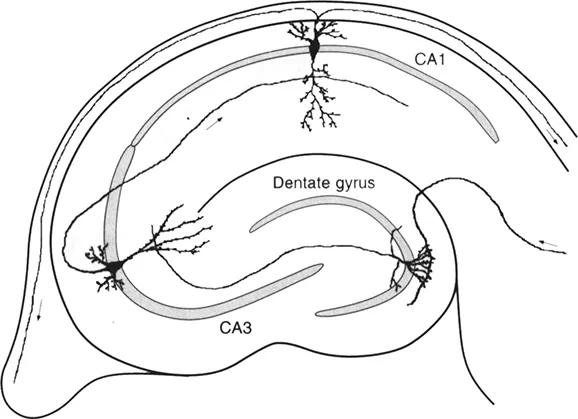

In the following paragraphs the slicing procedure and the knowledge surrounding it will be explained, with a bias towards the hippocampal slice. This bias results from the fact that the hippocampal slice is the most commonly used slice preparation today (Figure 1.1). The attraction of this slice is due to its clearly layed-out cytoarchitecture, where the cell bodies lie in various clearly visible cell bands, and dendrites make contact with fibers from known origin. A lot is known about the histology, as well as the pharmacology of the different areas of the hippocampus. Even though the hippocampus is the most widely used slice preparation, many others have been established in the last ten years. It is theoretically possible to cut any sort of slice from any region of the central nervous system.

Figure 1.1 Schematic drawing of a parasagittal hippocampal slice. Shaded areas indicate where the cell bodies of the principal excitatory cells are found, i.e. in areas CA1, CA3 and the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus. The remaining area within the slice contains interneurons and axons making synaptic contact onto the dendrites of the pyramidal cells. The flow of excitation within the hippocampus is indicated by the small arrows.

SLICING PROCEDURE

‘It is perhaps on this topic more than others where myths, unfounded dogmas, and notions based on intuition or anecdotal evidence tend to influence the choice of method’ (Alger et al., 1984). Despite the many different procedures employed, the main goal is to prepare a slice of tissue where the neurons, fibers, synapses and glia that are important to the experiment are in a viable condition.

The animalg used in preparing slices are most often small rodents: guinea pig, rat and mouse. It appears that younger animals produce better results than older animals mainly because they are more resistant to the traumatic and ischaemic insult of the slicing procedure. It seems that the speed of dissection is not nearly as important as the care taken in removing and slicing the tissue. Several studies point to the fact that the actual cutting of the tissue is the critical step. The removal of the brain tissue is done after decapitation of the animal or during deep anaesthesia. Decapitation tends to be slower but less bloody, and it seems to yield superior results.

Once the tissue is removed, it is normally cooled down to temperatures around 2-4°C by placing it in ice-cold oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) to minimize metabolic activity. The piece of tissue is then cut with a scalpel to obtain the desired tissue orientation and then glued onto a stage using cyano-acrylic glue. Cutting is then done in ice-cold ACSF using a vibratome, a mechanical instrument which cuts by slowly moving a laterally vibrating blade through the brain tissue. These instruments were originally designed for the preparation of histological specimens. The rate of advance and vibration amplitude of the blade are best set at the maximum values that will permit rapid cutting without compressing or ‘pushing’ the tissue. Small blocks of agar (2-5% made up in ACSF) can be glued onto the stage for additional support.

A ‘standard’ slice is cut at 400 μm thickness. This thickness is a compromise between retaining the cytoarchitecture and visibility, and the diffusion distances for oxygen and glucose. It can be shown that the limiting thickness of a cerebellar slice is about 450 μm at 37°C. Regions of the slices that are thicker than this value exhibit centrally-located necrotic cells, suggestive of hypoxic damage. This limiting thickness may vary in different brain regions according to the particular tissue demands.

After cutting, the slices usually need to be trimmed away from the surrounding tissue with fine scissors and forceps. The slices are then incubated at a temperature of around 36°C for at least forty minutes. Oxygenation and normal pH are maintained by bubbling the ACSF with 95% O2/5% CO2. This allows the tissue to ‘recover’ from the damage imposed by the preparation and adjust to the new extracellular milieu as well as to the changed metabolic activity. It has been suggested that during the incubation period cellular enzymes are released which help ‘soften’ the surface of the slice. This seems to be important for whole-cell recording. Following the recovery period, the slices are maintained at room temperature to keep metabolic activity low.

SLICE CHAMBERS

For experimental use slices must be kept in an environment providing appropriate oxygenation, pH, osmolarity, and temperature. In addition, depending on the techniques used, it is necessary to have excellent visual control, good mechanical access and stability. Most commonly used chambers allow the superfusion of ACSF across the slice. This imposes special demands on the mechanical stability of the superfusion system.

There are two different superfusion chamber designs where the slice either rests on a net at the gas-liquid interface (so-called ‘interface chamber’) or is totally submerged (‘submersion chamber’). The best design depends on the particular experimental requirements. Submersion chambers are normally used for whole-cell patch recording, whereas interface chambers are better suited for monitoring extracellular fields. It is known that field EPSPs are bigger in interface chambers probably due to the fact that in a submersion chamber the current can flow more easily into a bigger superfusion volume than if its extracellular space is restricted as it is in the interface chamber. Most of the slice chambers are temperature controlled and the superfusion rate of the ACSF is at least I ml/min. The flow rate determines the O2 and CO2 escape by diffusion as the perfusate travels along the tubing supplying the chamber. Flexible tubing is normally made out of Tygon™ which has low diffusion constants for O2 and CO2.

Mechanical stability of recordings in slices is determined, among other things, by the inflow and aspiration rates of ACSF and the balance achieved between them. Drainage is the most difficult factor to control. Mechanical stability can be disrupted by occasional gas bubbles which can be trapped in additional reservoirs not directly connected to the superfusion volume in the chamber. For recordings of any sort, it is important to keep the slice fixed to the bottom of the chamber. This is achieved by laying a grid of parallel nylon threads glued on a U-shaped flattened platinum wire on top of the slice (Edwards et al., 1989).

ACSF

Comparisons of the ionic composition of ACSF with in situ solution shows that the most significant differences are in the K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations. The higher concentrations used in vitro may well affect physiological properties of the slice. It is well known that divalent cations like Ca2+ and Mg2+ exert a stabilising effect on excitable membranes which will raise action potential thresholds. Further, both Ca2+ and Mg2+ have a profound effect on synaptic transmission. Note that the effective Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentration within the slice is smaller than the concentration in the ACSF due to the fact that a portion of Ca2+ and Mg2+ is chelated with phosphates in the solution as well as bound to proteins within the slice.

Anormal mammalian ACSF (rat) contains about (in mM): NaCl 124; KCl 3; NaHCO3 26; NaH2PO4 2.5; CaCl2 2.5; MgSO4 1.3, glucose 10.6. Different laboratories use slight deviations of this recipe. The important point is that the osmolarity of the solution is between 280 and 320 mOsm/1. Glucose is the primary energy substrate in this ACSF. pH is adjusted between 7.2 and 7.4. The final pH value is obtained by bubbling with CO2 (bicarbonate/C02-based buffering system). Bubbling the ACSF is normally done with carbogen, a gas mixture of 95% 02/5% CO2.

For preparations like the adult guinea pig brain, it is essential to cut slices in ACSF where sodium has been replaced iso-osmotically with sucrose. The reasons for this are currently unclear but lowering of the transmembrane sodium gradient will influence many membrane transporters and will change overall excitability.

The above mentioned composition of ACSF reflects the basic requirements for maintaining healthy slices. Depending on the experimental needs, the composition might have to be adjusted considerably, and perhaps additional constituents and/or pharmacological agents added. For example, working on NMDA ligand gated channel usually requires the addition of the co-agonist glycine to the superfusion solution.

TEMPERATURE

Although the body temperature of small rodents is around 38°C, most investigators maintain the slices at 30-35°C in the experimental chamber. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, it has been found that preparations survive longer, and in a healthier state at the lower temperature. Secondly, the higher humidity resulting from warmer solutions leads to the formation of droplets on recording and stimulating electrodes. These tend to fall off and result in mechanical instability during recordings. Many people tend to work at room temperature. However, as most of the biological processes have a Qjo of about 2, working at room temperature will slow biological processes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- SECTION 1 IN VITRO PREPARATIONS

- SECTION 2 ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL TECHNIQUES

- SECTION 3 HUMAN ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

- SECTION 4 APPLICATION OF DRUGS

- SECTION 5 MEASUREMENT OF ION CONCENTRATIONS

- SECTION 6 IN VIVO TECHNIQUES AND PREPARATIONS

- SECTION 7 HISTOCHEMICAL TECHNIQUES

- SECTION 8 BIOCHEMICAL TECHNIQUES

- SECTION 9 PRODUCTION OF ANTIBODIES

- SECTION 10 BLOTTING AND HYBRIDIZATION TECHNIQUES

- SECTION 11 EXPRESSION SYSTEMS

- SECTION 12 GENETIC TECHNIQUES

- SECTION 13 NEURAL GRAFTING

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Neuroscience Methods by Rosemary Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.