![]()

1

Gentic Technology and Society

Technology alternately has been praised by those who extol its benefits and condemned by those who view it as a harmful influence on society. Technology, however, does not exist independently; it has always interacted with the social and cultural context within which it functions. The values and institutions of a society in large part define the boundaries of the scope as well as the speed by which technological applications are accepted and used. According to Kieffer (1979: 416), science1 reflects the "social forces which surround it" and society may well write the rules to be followed in technological pursuits. Although subject to pressure for change by technology, the value system, passed from one generation to the next largely intact, is resistant to major alterations. Established social institutions, too, resist change and attempt to minimize alterations in the status quo. Societal priorities, therefore, always reflect existing social values and structures. Not surprisingly, technologies that challenge the most strongly held values and threaten existing social structures are less likely to be readily accepted.

Just as values shape the development of technology and set limits on it, so each technological application affects society. Technology reinforces and promotes certain values and patterns of social relationships and weakens or undercuts others. Despite the persistence of social values and structures, any innovation leads to some degree of change in life-style, causing priorities to shift and thereby making some values easier to attain and others more difficult. Although these changes are normally subtle and incremental, such as the gradual breakdown of the family in recent decades, the cumulative impact of technology is profound. All aspects of twentieth-century America reflect this pervasive influence of technology on values and institutions. The more salient and intrusive the technology (for instance, the automobile, television, and the contraceptive pill), the greater its potential impact on society.

It is difficult to demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between technology and society, however, because the relationship is interactive and dynamic. The question of whether changes in social structures and values follow or precede changes in technology cannot be answered conclusively. For instance, did birth-control technology produce public attitude changes toward sex and reproduction or, conversely, did changes in the social context produce a change in attitudes that led to acceptance of and therefore encouragement for the development of new methods of birth control? Some observers have opted for the latter explanation. They see social security and the threat of overpopulation as undermining older arguments against limiting family size, an attitude that results in support for more reliable birth-control methods (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare [DHEW], 1978: 5). These observers assert that "innovations in biobehavioral technology represent responses to other, larger social changes in the patterns of social policy, individual behavior, and ethical belief" (DHEW, 1978; 1). There is little doubt that the effects of technology on society are substantial, but there is also much evidence that technology is strongly responsive to societal inputs.

Technology and American Culture

Many observers have noted that American culture is dominated by a technological orientation (Ellul, 1964; Calder, 1970). According to Sinsheimer (1978: 34), we are addicted to technology: "We rely evermore upon it and thus become its servant as well as its master." Boorstein (1978: 60) asserts that our technological orientation can be traced to the experimental spirit reflected in the United States Constitution. "American experimentalism — in its older form of American federalism and in its more modern generalized form of American technology," he argues, has become the "leitmotif of American civilization." Gaylin (1975) adds that the mass successes of science and technology have made it an indispensable part of our culture.

The profound influence of modern technology on American society has led some critics to contend that the technological society is bound to fail for a variety of reasons. Marcuse (1964) exclaims that technology is by necessity a system of social control. Every advance in technology represses individual freedoms and blinds people to their real interests. Galbraith (1967) expresses concern for the emergence of the "technostructure" — the technical elite required for complex technical decision making. Most critical is Ellul (1964), who envisions a technological trap leading to progressive dehumanization and warns against the domination of human values by technique.

On the other hand, John Fletcher (1974: 99) does not agree that a technological society leads to dehumanization. As people make culture and take the initiative in the culture-making process, "the roots of dehumanization lie deeper in us than feedback from technique or technology." Fletcher states that we must look at values, not technology, for the root of our dehumanization. Callahan (1973: 260) adds that these "preachers against technology" offer little more than "provocative bedtime reading" because they fail to account for the "psychological principle of reality — that contemporary man cannot and will not live without technology." Emphasis should be shifted toward development of an "ethic of technology" that, according to Callahan, starts with the "tangible, ineradicable fact of technology."

Ferkiss (1969) goes further, noting that the danger lies not in the dominance of technology over society but in the subordination of technology to the values of bygone eras. To him, it is crucial that the "new technological man" fully understand the environmental and social consequences of each innovation and take responsibility for them. To many theorists, technology, culture, and the environment are inseparable and society must channel and control technology but not condemn it. "Just as technological invention cannot remove the need for social invention," Spilhaus (1972) warns, "neither should our slowness in changing outmoded social practices, institutions, and traditions be allowed to slow technological realization of potential benefits to all." Calder (1970), for instance, proposes new forms of social control to direct the "staggering new powers" of technology toward perfection of the human condition.

Partially in response to the critics of technology, Weinberg (1972) introduced the concept of "technological fix" as a solution to the myriad social problems we face, including those created by technology. For instance, if we pollute the environment, we can develop new enzymes to break down the oil, neutralize the chemical wastes, and so on. Even though these measures do not solve the core problems, they might delay or obscure the consequences until a day when we are able to overcome them. In the meantime, these intermediate technological fixes might improve the world's condition without requiring major attitudinal or structural changes (Freeman, 1974: 50).

Although the concept of the technological fix has engendered discussion (Etzioni, 1973; Ellison, 1978), such transfusions not only fail to solve major problems but also might compound them for the future. By treating the symptoms, the core problems are left to fester and grow, often unnoticed, until it is too late. Sinsheimer (1978) notes that the application of one technological fix seems to lead to another, and another, and so forth. It appears that societies can no longer afford to depend solely on these expedient but short-term fixes that technology offers.

Although societal problems most likely will be approached through technological means, alterations in social structures, values, and perceptions of the problems are also necessary. More comprehensive and well-conceived strategies are needed for dealing with the complex problems that include social, moral, and political dimensions in addition to the technical. As Kass (1971: 781) asserts, questions of the use of technology are always moral and political ones, not simply technical ones.

Technology and Politics

Politics is the primary means through which resources are authoritatively allocated to the various groups and individuals in society. Within the political arena, each interest attempts to resolve conflicts over the distribution of social goods in its own favor, thereby maximizing its relative social advantage. Much decision making in politics therefore revolves around the resolution of conflict. Technology is intricately related to politics, as it generates conflict by rewarding some interests and depriving others. Each technology brings with it forces that alter the existing competitive structure among these interests.

Technology inevitably is accompanied by costs and deprivations as well as benefits and new opportunities. Although the distribution of such costs and benefits varies from one innovation to the next, it is never socially neutral. Some groups are rewarded while others are penalized; certain interests gain a great deal while others record minimal or no gains. Often the costs are borne by groups that do not share in the benefits at all. Obviously, people who see a technological development in their interest will tend to support it; those who do not will oppose it or at least remain uncommitted. The wide diversity and large number of groups in the United States ensure that each technological development is a potential political issue. Contributing to this has been the trend in the United States over the last several decades toward broadened notions of participatory democracy, a trend that has encouraged many additional conflicting groups to enter the political arena to gain access to decisions and to press for their demands. In assessing any new technology, therefore, it is crucial to analyze the potential alterations in the distribution of resources in its application.

In addition to political conflict resulting from changes in the distribution of resources, technology also produces shifts between private and public interests and obliterates traditional distinctions between them. These alterations, in turn, have broad implications for the public-policy process as concern focuses on the expanded role of government in matters previously considered to be private (for example, procreation). Nelkin (1977: 412) sees democracy threatened by this tendency of a technological society to blur distinctions between private and public realms as well as by the utilization of sophisticated decision-making techniques that undermine democratic principles. Also of concern to Nelkin are the growing tendency to concentrate political power in those who control technical information and the danger of policy decisions becoming so technical that politicians defer to the technocrats. This interrelationship between technology and politics is critical in understanding why technologies are politically divisive.

Genes and Environment

A continuing controversy in social science, and one that has recently been fueled by the debate over sociobiology, relates to the degree to which human behavior is a result of genetic endowment. There is no attempt to discuss the intricacies of that argument here, but it is necessary to address the problem and demonstrate the need to include genetic components in our models. Obviously, how one views the need for and desirability of human genetic intervention is dependent to a large extent on one's conception of the contribution of the genetic component. The opposition engendered by even suggesting the application of biological models to social processes is a preface to the intense disagreement over implementation of genetic policies discussed in this book.

Competing Models: Genes Versus Environment

The debate over the extent to which humans are products of genetic and environmental variation is best pictured as a continuum with one extreme representing the environmental determinist position and the other the genetic determinist position:

| Genetic | Interactive | Environmental |

| Determinism | Model | Determinism |

The pure environmental model is based on the assumption of a tabula rasa, or blank state, in which all human beings are deemed to possess exactly the same potential at birth. Differences exhibited among humans, therefore, are the result solely of variations in environmental conditions. At the opposite extreme is the theory of genetic predestination, which holds that all differences among humans are the result of variation in genetic endowment (Darlington, 1969). Under this model, few attributes can be altered substantially because they are predetermined by the genes. According to Dobzhansky (1973: 31), traditional caste systems are organized on the basis of this extreme model.

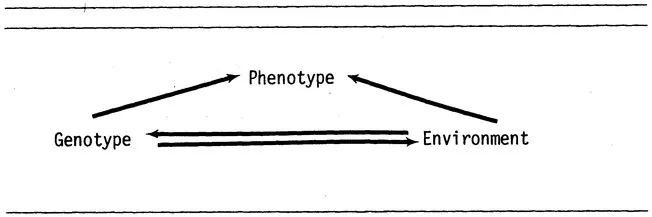

Although few scholars today totally subscribe to either of these pure deterministic models, there is a tendency to gravitate toward one or the other end of the continuum. In general, social scientists and humanists find the environmentalist assumptions more consonant with their perception of reality. White (1972), for instance, suggests that the assumption of individual uniqueness of the genetic model runs counter to the accepted paradigm of the social sciences — that individuals are malleable through cultural and political processes. Conversely, traditional biological premises suggest a convergence of biologists toward the opposite pole, though there are many notable exceptions (e.g., Dobzhansky) near the center. There appears to be a growing awareness in most disciplines of the necessity to use more complex interactive models,2 where genetic and environmental factors interact to produce a phenotype, but there are pressures in each field to retain traditional paradigms.

The Interactive Model: Genes and Environment

Despite these constraints and the built-in resistance to an interactive model, such a model is most accurate and meaningful for describing the complexity of human existence. Dobzhansky (1973: 25) states that sociological and biological variables are almost always intertwined in humans and that diversity is a joint product of genetic and environmental differences. Even at the micro level

an individual's physical and mental constitutions are emergent products, not a mere sum of independent effects of his genes. Genes interact with each other, as well as with the environment . . . gene B may enhance some desirable quality in combination with another gene A1, but may have no effect or unfavorable effects with a gene A2. . . . For this reason ... it is not at all rare that talented parents produce some mediocre offspring, and vice versa. [Dobzhansky, 1973: 35]

Although the interactive model presumes that both genetic and environmental factors must be considered intricate and essential components of human existence, it does not suggest that they are equally important in each case, nor that variation can be parceled out to each.

White (1972) applies an interactive populational approach to the political system. According to White, neither nature nor nurture solely explains human behavior; therefore we need a more complex paradigm in which the complete genetic endowment interacts with environmental influences to produce a phenotype (see Figure 1.1). The result of this interaction is twofold (p. 1215). First, "individuals with similar genotypes will vary significantly in their phenotypes as a result of environmental differences." Second, and with more direct political implications, is "the alternative possibility that within similar environments individuals with varying genotypes will differ accordingly in observed behavior."

The concept of genetic diversity suggests, then, that individual capacities do vary and beyond a certain threshold are limited, no matter how favorable the environmental conditions. Although most people would accept such a position as it relates, for instance, to artistic or musical abilities, environmentalists reject its applicability to most areas of human behavior. This concept often leads to cries of racism. White (1972: 1211), however, asserts that this represents an "unreasoning prejudgement" on the part of these critics and that they have, perhaps consciously, "compounded the problem by implying . . . that genetically-grounded approaches are necessarily racist." Populational thinking views discrimination applied wholesale to classes or races of people as without foundation. On the other hand, this fear of the environmentalists has been reinforced by the use (misuse) of genetic theories by some scientists (e.g., William Shockley) to demonstrate IQ differences by race.

FIGURE 1.1 An Interactive Paradigm

Source: White, 1972: 1215.

Dobzhansky (1973: 44) contends that genetic diversity is a "treasure with which the evolutionary process has endowed the human species" and he sees no inherent conflict between genetic diversity and various social, economic, and political conceptions of human equality. Corning (1978: 25-26) points out that it is estimated that humans hold 95 percent of their genes in common and that 5 percent of each individual's genetic endowment is unique. As both are equally fundamental to the evolutionary process, it might be most natural to emphasize the 95 percent of the genes, held commonly, that define us as Homo Sapiens.3

White (1972: 1234) reiterates the political aspects of genetic diversity by stating that the "policy-maker—even more than the social scientist — must seek out rather than cover up individual differences." We must realize that each individual, despite his or her racial or social characteristics, is unique and must be treated so. As Ernst Mayr (1967: 833) points out, "Nothing is more undemocratic or more apt to destroy equal opportunity than forcing human beings with exceedingly different aptitudes ...