![]()

Part 1

The Planned and Unplanned Economies

Introduction to Part 1

MORRIS BORNSTEIN

The Soviet Union is the prototype of a socialist, centrally planned economy, in which the state authorities are supposed to control resource allocation and income distribution through comprehensive plans and detailed administrative orders. But, in practice, Soviet economic planning is both imperfect and incomplete. Ambitious plans often cannot be achieved and frequently must be revised during the period they cover. Moreover, in the USSR there are important markets over which state agencies exercise only partial, if any, control.

To make detailed plans for production and supply, central planning agencies and branch ministries prepare "material balances" covering the total amount and composition of the sources and uses of tens of thousands of commodities. The sources include domestic production, imports, and inventories at the beginning of the period. The uses comprise intermediate use by processing industries, final domestic consumption by households and by government agencies (for both civilian and military programs), exports, and inventories at the end of the period.

Linked to these material balances are detailed "technical-industrial-financial" plans for individual factories, farms, and retail establishments. The plans cover authorized inputs of labor and materials; output assignments; the corresponding costs of production, sales revenue, and profits; and capital investment programs.

Although material balances and associated enterprise plans are usually "consistent" (i.e., balanced on paper), they are often not "feasible" (i.e., actually attainable in practice). Shortages of inputs and finished products are widespread, and many firms fail to meet some of their output targets and investment schedules. One reason is the inability of planning and administrative agencies to collect and process all of the enormous amount of relevant data in a large, complex, and changing economy that produces, according to Soviet experts, over 12 million different items. A second reason is the persistent tendency of planners, in response to pressures from political leaders seeking rapid growth, to establish overly ambitious, excessively "taut" plans with unrealistically low input-output ratios and inventory levels.

In Chapter 1, R. W. Davies explains why the system of central planning and administrative supervision of the economy was adopted in the USSR in the late 1920s to mobilize resources for rapid industrialization. Although this system worked imperfectly, it did succeed in achieving some of the main objectives of the Soviet regime. However, after the death of Stalin in 1953, it became increasingly evident to Soviet leaders, economists, and administrators that this "mobilization" model was unsuitable for a "mature" Soviet economy already industrialized and with high rates of labor force participation and more than one-fourth of national product going to investment. In the current "intensive" phase of Soviet economic development, the main challenge is not to obtain more inputs of labor and capital but rather to increase their productivity and to stimulate technological progress in order to raise the quantity and especially the quality of Soviet output. In pursuit of these aims, the Soviet regime has made some changes in economic organization, planning techniques, pricing, and incentive schemes. But, as Davies shows, these changes have been limited, and their effects relatively modest.

Because Soviet economic plans are so comprehensive, detailed, and ambitious, it is not surprising that they are not, and cannot be, carried out as drawn up and promulgated. Instead, plans are not completely fulfilled, unplanned actions occur, and plans are frequently revised during the period they cover. In Chapter 2, Raymond P. Powell examines how central planning bodies, administrative agencies, and enterprise managements analyze and respond to problems that arise in the execution of plans. He discusses how decision makers identify and measure scarcities in the absence of market-clearing prices for most goods and services. He explains the ingenious methods used to attempt to overcome shortages and to achieve – or at least simulate – plan fulfillment. Powell finds that the Soviet economic system is best characterized as a combination of "planning cum improvisation," in which formal and informal adjustments at various levels during the implementation phase correct some of the errors in economic planning.

Although it is common to think of the USSR as a centrally planned economy, in fact many kinds of markets operate in it, for various reasons. First, as in official retail trade, the market is the only mechanism capable of successfully distributing thousands of kinds of state-produced consumer goods and services among millions of Soviet households with widely divergent money incomes and tastes. Second, some markets arise because of shortages caused by deficiencies in the production, pricing, and distribution of output. In such markets individuals with scarce goods sell them above official prices, or enterprises barter materials with other firms having complementary shortage/surplus positions. Third, there are markets for privately produced consumer goods and services that meet demands not satisfied by state plans assigning high priorities to investment and military programs at the expense of consumption.

The resulting complex system of legal, semilegal, and illegal markets in the USSR is described in Chapter 3 by Aron Katsenelinboigen and Herbert S. Levine. They explain why each type exists, what is traded in it, and the roles of state enterprises, collective farms, and households as buyers and sellers.

Thus, besides the official, socialist, centrally planned economy usually described in Soviet and Western textbooks, the USSR has a "second economy." It consists of (1) unofficial operations by state enterprises seeking to fulfill their plans; (2) legal private activities, such as the production of food on garden plots and its sale on the "free" collective farm market; and (3) illegal private activities in trade, services, and even manufacturing.

Chapter 4 by Gregory Grossman examines the scope of this second economy, the reasons for its existence, and its role in economic crime and the corruption of officials. He shows that the second economy has not only considerable economic significance but also important ideological, political, and social implications. Thus, any assessment of the size, operation, and problems of the Soviet economy must take second-economy activities into account.

![]()

1

Economic Planning in the USSR

R. W. DAVIES

The Soviet Planning Process for Rapid Industrialization

An Outline of the System

The Soviet government set itself the objective of a more rapid rate of industrialization, with a greater investment in capital-consuming industries and processes, than could be achieved within the framework of the market economy of the 1920s. The main objective was achieved, but with a much slower increase in living standards (consumer goods, agricultural output) than had been intended. To enforce its priorities, the Soviet government abandoned the major assumptions of its earlier policy.

1. A market relationship with the peasant was replaced by administrative or coercive control over his output. The centers of economic and political resistance in the rural commune were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of kulak families were expelled from their home villages. Twenty-five million individual peasant farms were combined into 250,000 collective farms (kolkhozy), one or several to each village. The old boundaries and strips were destroyed, and most land and cattle were pooled and worked in common. Agricultural machinery was gradually made available from several thousand state-owned machine and tractor stations (MTS). The kolkhoz was required to supply a substantial part of its output to the state collection agencies at low fixed prices in the form of compulsory deliveries. These supplies were then used by the state (a) to make available a minimum amount of foodstuffs to the growing urban population, and (b) for export. Exports of grain fell from 9 million tons in 1913 to 2 million tons in 1926-27 and 178 thousand tons in 1929. They rose (temporarily) to 4.8 million tons in 1930 and 5.1 million tons in 1931, and this increase was used to pay for imports of equipment and industrial materials.

2. Inflation was permitted to develop. The wages of the expanding industrial and building labor force were partly met by increasing the flow of paper money. Prices began to rise, but the inflation was partly repressed through price control in both the producer goods market and the retail market. (Private shops and trading agencies were taken over by the state to facilitate this.) For several years (1929-35) a rationing system was introduced in the towns, supplemented by state sales of goods above the ration at high prices. Foodstuffs were also sold extensively by the peasants at high prices on the free market. In this way, the available supply of consumer goods and foodstuffs was distributed over the old and the new urban population, and consumption per head in the towns was forced down.

3. Within industry, the system of physical controls which had already existed during the 1920s was greatly extended. Prices were fixed, and there was no market for producer goods. Instead, materials and equipment were distributed to existing factories and new building sites through a system of priorities, which enabled new key factories to be built and bottlenecks in existing industries to be widened. The plan set targets for the output of major intermediate and final products, and the physical allocation system was designed to see these were reached.

To sum up these first three points: the policies of 1928-32 enabled a new allocation of GNP to be imposed on the economy. The discussions of the 1920s had assumed that savings would be made by the state within the framework of a dynamic equilibrium on the market between agriculture and industry. This placed a constraint on the proportion of GNP which could be invested, and on the allocation of that investment (investment in consumer goods industries would need to be sufficient to enable the output of consumer goods to increase at the rate required for equilibrium). Now this constraint was removed. Urban and rural living standards were temporarily depressed, and physical controls were used to divert resources to the establishment of new capital-intensive industries and techniques which gave no return during the construction period and were relatively costly in the medium-term. This method of obtaining forced savings through physical controls resembled the wartime planning controls used in capitalist economies to shift resources toward the end product of the armament and maintenance of the large armed forces. In the Soviet case, the end product was the capital goods industries and the maintenance of the workers employed in building and operating them. But in both cases a shift in the allocation of resources which could not easily be achieved through manipulating the market mechanism was achieved through direct controls.

4. However, the system was not one simply of physical controls. Within a few years, the following features, stable over a long period, supplemented the system so far described.

- Each peasant household was permitted to work a private plot and to own its own cow and poultry. After obligations to the state had been met, the separate households and the kolkhoz as a unit were permitted to sell their produce on the free market ("collective farm market"), where prices were decided by supply and demand. Here an important part of all marketed foodstuffs was bought and sold. The large flow of money to the peasants through these sales compensated them for the low prices they received for their compulsory deliveries to the state.

- With some important exceptions, the employee was free to change his job. A market for labor existed, if a very imperfect one, and wage levels were formed partly in response to supply and demand. A corollary of this was that cost controls and profit-and-loss accounting were introduced in industry, to supplement the physical controls.

- Rationing of consumer goods was abolished, and an attempt was made to balance supply and demand on the consumer market as a whole and for individual goods through fiscal measures, notably a purchase tax (the "turnover tax") differentiated according to commodity.

5. A large variety of unplanned and even illegal activities between firms supplemented and made feasible the rather crude controls of the central plan and must be considered as pan of the logic of the system. Black and "gray" markets for consumer goods emerged as a result of the shortages which, as we shall see, were endemic in the system.

The Planning Process

In this section, the planning process is described as it operated in 1935-41 after the abolition of the rationing of consumer goods, and again in the postwar years from 1947 onwards. It should be borne in mind, however, that many of its features continue without basic alteration even now. The modifications introduced after Stalin's death in 1953 are discussed below.

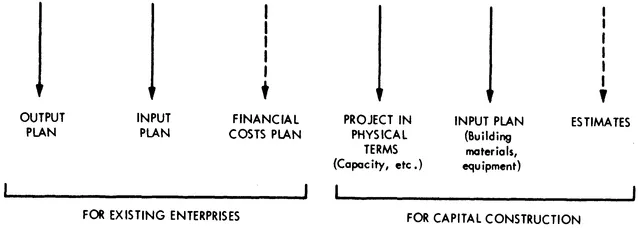

We have so far established that Soviet plan controls during rapid industrialization may be divided schematically as in Figure 1.1. Each enterprise received a set of output targets and input allocations with which to fulfil them. At the same time its monetary expenditures were controlled by financial or cost plans, which were less important to it than its output plan, but which came into operation if the pressure from above for higher output led the enterprise to increase its money expenditures excessively.

FIGURE 1.1

Principal Planning Controls Over Industrial Activity

Disaggregation

A key problem for the central planners was to disaggregate their major decisions so that they would be enforced at the plant level, and to aggregate information and proposals so as to be able satisfactorily to take into account the effect of their past and present decisions on different parts of the economy. In Soviet planning, this was normally dealt with in the following ways:

1. Economic organization was adapted to handle this problem.

- Factories were placed under the control of ministries or their production departments (glavki), each of which was responsible for a particular group of products (e.g., iron and steel, motor vehicles). Each ministry was given very considerable powers over its constituent firms, each of which usually consisted of a single factory. The government was therefore, to a considerable extent, concerned only with handling transfers between industries.

- Smaller factories producing low-priority items were placed under the control of the government of one of the constituent republics, or under local authorities. In the past, the government tended not to bother with them, and to treat allocations to them as a residual.

- Within the State Planning Committee (Gosplan), which was an advisory body to the government, and within each ministry or subministry, departmental organization mirrored the planning arrangements. In the iron and steel industry, for example, there were separate departments of the ministry responsible for sales of the industry's product, for supplies to the industry, for production plans of iron and st...