The Stationers’ Company of London, chartered as late as 1557, grew rapidly and continued to rise so remarkably that anyone could recognise its steady growth during the second half of the century. Promoters of the rise were a sizable group of readers and purchasers of books. Books are not the necessaries of life, as are food and clothing, but an intellectual luxury and pastime. Yet they are not that sort of luxuries which, like stage performances, can be enjoyed by anyone who can afford the cost of admission and has time to spare. Unless for ornament or display, they would be commodities of no meaning and value to the illiterate. Therefore, those who promoted the stationers’ prosperity were citizens who were blessed with reading ability in addition to economic surplus and sufficient time.

§1

Within the organisation of the Stationers’ Company, the economic power of publishers specialising in publishing and selling books gradually eroded that of printers, limited only to a small number, specialising in producing books. Although the printers were being reduced to mere providers of labour as trade printers, that is, printers who print books for publishers, some of the publishers were steadily accumulating wealth to rise to proprietorship with the primary key for publication and distribution.1 Such a change within the Company was a phenomenon common to all guilds of manual trade in the second half of the sixteenth century. There were, on the one hand, groups of workers who earned their daily bread by offering labour for wages and, on the other hand, groups of men who began to accumulate wealth in proportion to their resources by merely distributing commodities produced by dayworkers. This social phenomenon may be called the emergence of an entrepreneurial class, and such economic upheaval during the second half of the sixteenth century led English people through social unrest eventually to a civil and capitalistic society.

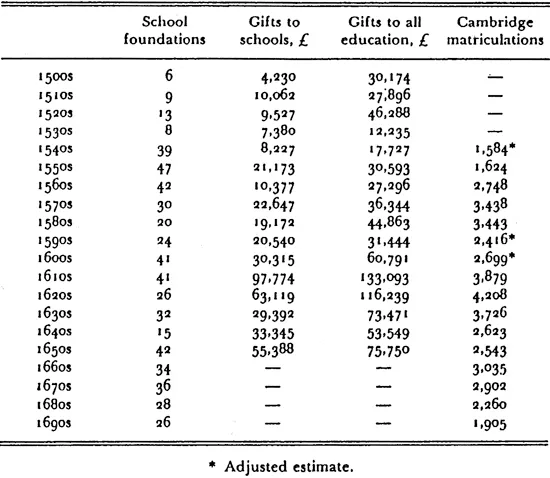

School education in mid-sixteenth-century Protestant England played a great part in the intellectual advancement of civil society. It was in 1535 that Henry VIII (1509–47) called himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England and began to suppress Catholic churches. Protestant England, as if suffering from a fever, started enthusiastic investment in education. The national aspiration for learning grew stronger during the reign of his successor Edward VI (1547–53). The national enthusiasm did not subside in the reign of Mary I (1553–58), a Roman Catholic, and remained as strong during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). This enthusiastic passion for education in the mid-sixteenth century onwards was expressed in a concrete form not only in gifts to schools but also in newly founded schools. Table 1.1 is from Cressy’s book.2 It shows the remarkable national trend of educational enthusiasm. Although Catholic England had on average none or only one new school founded in a year, Protestant England suddenly saw on average four new schools in a year until the end of the first ten years of Elizabeth I’s reign. Another ten years saw three new schools founded every year. Gifts to schools and to all education also doubled from the reign of Henry VIII to the reigns of Edward VI and Mary I. Some ten years afterwards, suggesting the gifts had been highly productive, matriculations in Cambridge also increased remarkably in the first ten years of Elizabeth I’s reign.

Table 1.1 Educational progress, 1500–1700 [Cressy (1977), 15; Cressy (1980), 165.]

The domestic impact of Henry VIII’s proclamation of the Church of England resulted in a vigorous and effective doctrinal propaganda by printers for the benefit of both Catholic and Protestant. The active propagation was primarily aimed at the leaders of both parties, but its collateral target was a growing number of people who had learned to read books as the result of this sudden educational enlightenment. It is not easy to know how in fact readers increased in number. But one can get a glimpse of this in an act of Parliament passed in 1543, several years after the proclamation of the Church of England.3 It concerns the reading of the English Bible and prohibits from reading it such people as women below gentry rank, craftsmen, apprentices, journeymen, servants of the rank of yeomen and under, husbandmen and labourers—all belonging to the lower classes of society. That the Parliament had to pass this prohibition specifying people of various social classes indicates, no doubt, that there was already so large a number of people who could read books that the Parliament had to legislate for this. According to this act, women above gentry rank were free to read the Bible for themselves but forbidden to read it to members of their families. It was only noblemen, gentlemen and merchants who were allowed to read it to their own families. From the viewpoint of readership, however, it is not very important whether the act was actually observed or not because the issue of an act and its subsequent observation are different matters. More important is that the act expressly mentioned books excluded from prohibition. Among them were all the books printed before 1540, The Canterbury Tales and other works by Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343–1400), works by John Gower (?1330–1408) and stories of men’s lives. These works in verse or prose would have been sources sufficient enough to foster a growing group of readers of literary works.

An ordinary practice of the Church was to discriminate men of rank and wealth in its favour, but it would be worth noting that Henry VIII in the act of 1543 treated merchants on equal terms with men of rank and wealth. In fact, merchants engaging in foreign trade and, in particular, some of those dealing with raw and processed wool had successfully had great economic power by the end of the fifteenth century and their wealth had been already attested by their tombs decorated with their prostrate brass statues. This practice was no different from that of noblemen and gentlemen of power and wealth.4

Those merchants, having accumulated wealth, rocked the feudalistic power structure violently, took the economic leadership in society in the course of the collapse of feudalism and exerted themselves so as to create a civil and capitalistic society. Although merchants were quick to show their presence in a structurally powerful and predominant social class, craftsmen or artificers who, like printers, could sometimes be their intellectual agents had to remain as they had been in the past and support, as the masses, the changing society under their control.5 Merchants and craftsmen were the new representatives of the two opposite social classes in the course of the collapse of feudalism and the rise of capitalism. It was quite natural that various social phases created by the two representatives should soon become source material for prose writers and playwrights who wanted to offer new elements to print cultures of the time.

Laura Stevenson carried out a survey of literary works printed during the reign of Elizabeth I in which merchants appear. She selected 296 publications: 107 plays and 189 ‘best-sellers’ which were printed three times within ten years (that is, 79 religious books, 48 works of fiction and poetry, 20 handbooks of instruction, 16 histories, 14 medical and scientific pamphlets and 12 collections of essays and aphorisms).6 Table 1.2 is based on her ‘Chronological list of popular works in which merchants appear’.7 The asterisk in ‘Drama*’ and ‘Best-sellers*’ indicates the number of references to them that appear ‘only in the dedication … or in a discussion of estates of the realm … or in a minor dramatic scene’.8

This table shows that merchants, not surprisingly even in the early years of Elizabeth I’s reign, already appeared in ‘best-sellers’, whereas their first appearance in drama occurred only in the 1580s, years after the appearance of playhouses open to the general public. Shakespeare is one of the earliest playwright who wrote for the audiences of these public playhouses. His contribution to this table amounts to three during 1586–1600, if Stevenson’s table is based on the date of composition which was perhaps immediately followed by a stage performance. The three contributions by Shakespeare are Vincentio, a merchant from Pisa, in The Taming of the Shrew (composed 1589; staged date unknown; printed 1623), Egeon, a merchant from Syracuse, in The Comedy of Errors (composed 1590−93; staged 1594; printed 1623) and Antonio, a merchant of Venice in The Merchant of Venice (composed 1596−98; staged date unknown; printed 1600).9 Considering Shakespeare’s growing popularity, his contribution seems rather small, only less than 8 per cent of his known plays. But as time passed, drama and best-sellers became well-matched in terms of frequency of their appearance in print cultures. The table shows, as a whole, that merchants, predominant in a civil and capitalistic society, appeared on average in about 23 per cent of all the works examined—that is, 25 per cent of plays and 22 per cent of best-sellers. These figures cannot be taken lightly. They attest that merchants were playing an important role in society and influential enough to attract playwrights and ‘best seller’ authors as well as their readers.

Table 1.2 Publication, 1558–1603, of popular works in which merchants appear [Stevenson (1984), 246–8]

§2

The common people’s enthusiasm for education was aroused, no doubt, by the proclamation of the Church of England and contributed greatly to the improvement of literacy of various social classes. How their enthusiasm was expressed in drama will be discussed in the next chapter, but here I would like to confirm in statistical terms the improvement of literacy linked directly with their educational enthusiasm.

Anyone in those days who could not write his or her name wrote only an X mark when required to sign a document. But anyone who was able to write even with some difficulty was usually willing to execute with pen and ink his or her signature, no matter how good or poor it was.10 These two different ways of signing documents are generally regarded as the criterion for literacy. According to David Cressy, who surveyed literacy in England during 1560–1580 on the basis of this criterion,11 the literacy of tradesmen in the diocese of Norwich, the second largest town in England in those days, rose to more than 60 per cent, with an increase of about 20 per cent. The literacy of East Anglian yeomen, who were in a better situation, also rose to about 75 per cent from about 45 per cent. The state of things further north in the diocese of Durham was also similar; the literacy of tradesmen improved from less than 30 per cent to more than 50 per cent. As a result, there were practically no illiterate gentlemen. In London, the people’s especially strong enthusiasm for education appears to have contributed to a much more rapid and conspicuous rise in literacy of every social class. The literacy of women and apprentices would deserve special mention in this context.12 In about the same period, according to Cressy,13 82 per cent of the apprentices and 69 per cent of the servants in the City and Middlesex were able to sign, whereas only 24 per cent of the servants (although there are no materials about apprentices) were able to write their names in such dioceses far from London as Durham, Norwich and Exeter. In other words, the number of the literate servants in these remote dioceses was about one third of that in London and Middlesex. It is only women that showed no difference in literacy between London and the provinces until about 1630, and about ten per cent of women were able to write their names. In any event, the improvement of literacy was remarkable from the beginning of Edward VI’s reign to the end of the first twenty years of Elizabeth I’s reign.

This fact, however, appears to have nothing to do with the successive publications of the Bible, although, as already mentioned, the proclamation of 1543 pr...