Human-Centered Computing

Cognitive, Social, and Ergonomic Aspects, Volume 3

- 1,504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Human-Centered Computing

Cognitive, Social, and Ergonomic Aspects, Volume 3

About this book

The 10th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCI International 2003, is held in Crete, Greece, 22-27 June 2003, jointly with the Symposium on Human Interface (Japan) 2003, the 5th International Conference on Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics, and the 2nd International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. A total of 2986 individuals from industry, academia, research institutes, and governmental agencies from 59 countries submitted their work for presentation, and only those submittals that were judged to be of high scientific quality were included in the program. These papers address the latest research and development efforts and highlight the human aspects of design and use of computing systems. The papers accepted for presentation thoroughly cover the entire field of humancomputer interaction, including the cognitive, social, ergonomic, and health aspects of work with computers. These papers also address major advances in knowledge and effective use of computers in a variety of diversified application areas, including offices, financial institutions, manufacturing, electronic publishing, construction, health care, disabled and elderly people, etc.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Section 1

Ergonomics and Health Aspects

Position of the arm and the musculoskeletal disorders

Arne Aarås | Gunnar Horgen |

Abstract

1 Introduction

- The position of the upper arm relative to vertical.

- Supporting the forearm.

- Position of the forearm.

2 Laboratory studies

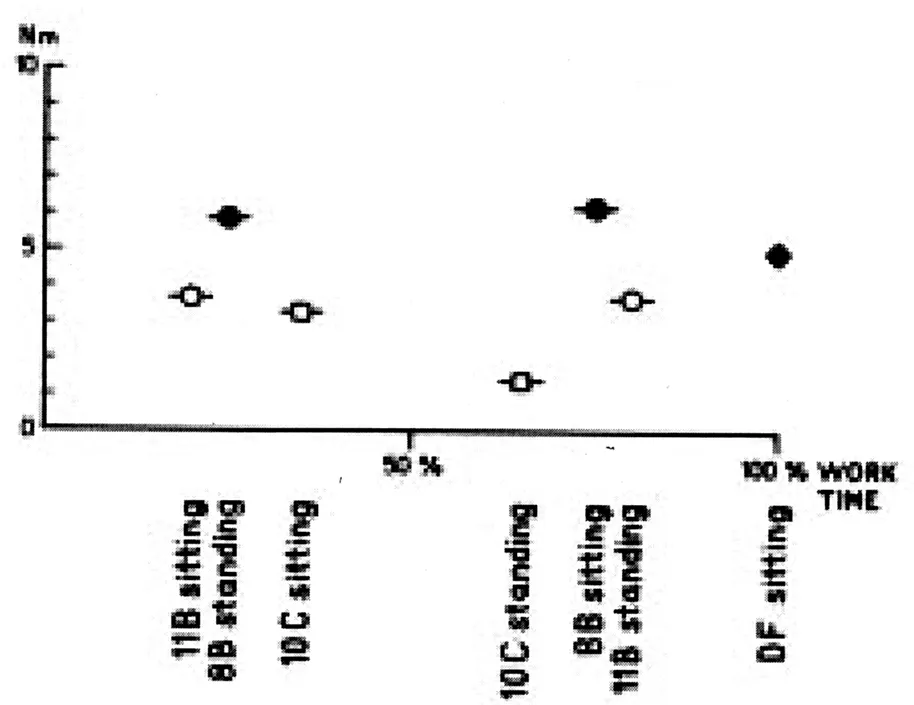

2.1 Postural load for various work posture

2.2 Postural load of the forearm in neutral and pronated position

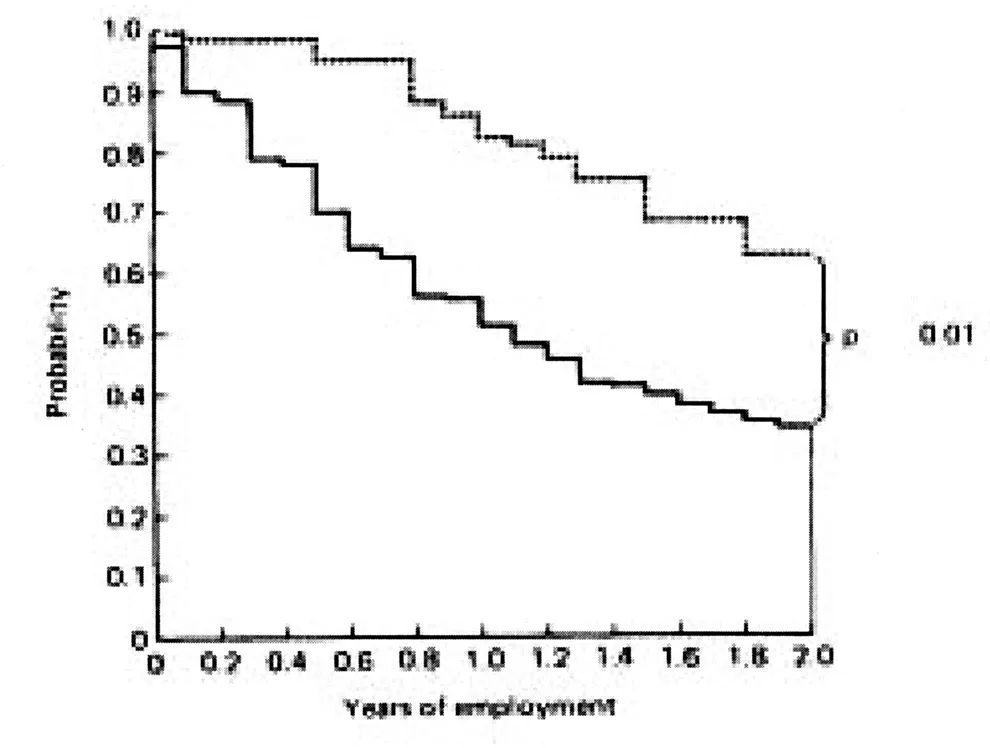

3 Prospective field studies

3.1 The shoulder moment and the musculoskeletal pain

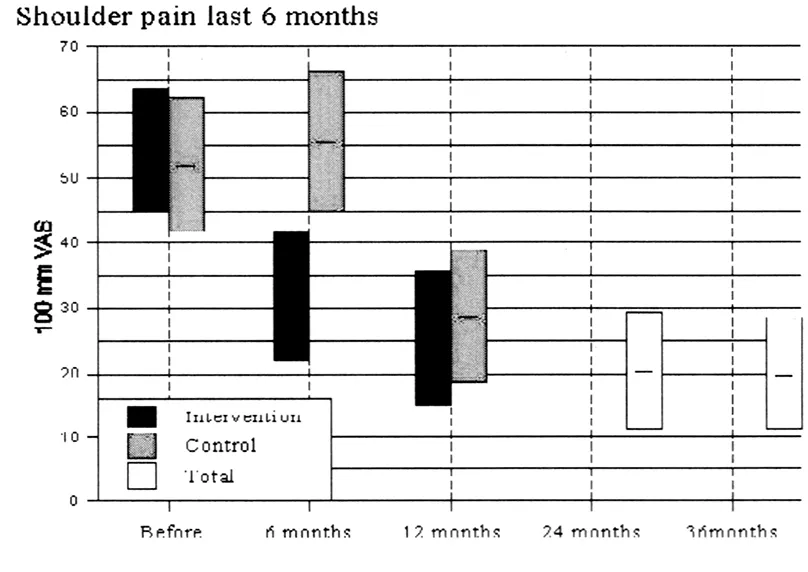

3.2 Supporting the forearm and musculoskeletal pain

3.3 Supporting the forearm in a neutral position and musculoskeletal pain

4 Conclusion

5 References

- Aarås, A. (1994). The impact of ergonomic intervention on individual health and corporate prosperity in a telecommunications environment. Ergonomics, vol. 37, no. 10, 1679-1696.

- Aarås, A., Fostervold, K. I., Ro, O., Thoresen, M. & Larsen, S. (1997). Postural load during VDU work: a comparison between various work postures. Ergonomics, Vol. 40, No. 11, 1255-1268.

- Aarås, A. & Ro, O. (1997). Work load when using “mouse” as input device. A comparison between a new developed “mouse” and a traditional “mouse” design. International Journal Human Computer Interaction, Volume 9, No. 2.

- Aarås, A. & Westgaard, R. H. (1987). Further studies of postural load and musculoskeletal injuries of worker at an electro-mechanical assembly plant. Applied Ergonomics 18,3, 211-219.

- Aarås, A., Horgen, G., Bjørset, H-H., Ro, O. & Thoresen, M. (1998). Musculoskeletal, visual and psychosocial stress in VDU operators before and after multidisciplinary ergonomic interventions. Applied Ergonomics, 29, 335-354.

- Aarås, A., Dainoff, M., Ro, O. & Thoresen, M. (2002). Can a more neutral position of the forearm when operating a computer mouse reduce the pain level for Visual Display Unit operators? A prospective epidemiological intervention study: Part III. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 30/4-5, 307-324.

Physical Environments for Human Computer Interaction in Scandinavia

[email protected]

Abstract

1 Introduction

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Section 1. Ergonomics and Health Aspects

- Section 2. Cognitive Ergonomics

- Section 3. Engineering Psychology

- Section 4. Online Communities, Collaboration and Knowledge

- Section 5. Applications and Services

- Section 6. Design & Visualisation

- Section 7. Virtual Environments

- Author Index

- Keyword Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app