- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The World of the Italian Renaissance

About this book

Originally published in 1982, this book tackles the underlying problem of what is meant by 'the Renaissance' and outlines those social, economic and topographical factors which triggered it off. It covers a number of subjects, the family, war, trade, religion and art but recognizing that the Renaissance was essentially an urban growth it focusses on 7 great Italian cities: Florence, Rome, Venice, Milan, Urbino, Mantua and Ferrara. It also includes studies of some extraordinary Renaissance individuals: Federigo Montefeltro, Isabella d'Este, Machiavelli, Baldasssare Castiglione, and the Medici clan, among others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The World of the Italian Renaissance by E. R. Chamberlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The geographical expression

The four powers

There had been no fall of the Roman Empire in the sense of an abrupt and cataclysmic ending as there was for the end of the Byzantine empire in 1453. Looking back down the long perspective of their history, Italian historians were hard put to say just when the Empire had come to an end. Some, the idealists, tended to link the ending of the Empire with the coming of the Caesars. Others, more logically, chose the sack of Rome of AD 410 as the dividing point between the ancient and the modern worlds. Few paid much attention to the date AD 476 when the last Roman Emperor of the west, the ironically named Romulus Augustulus, abdicated and brought the western Empire legally to a close.

There was no dramatic break, nothing clearcut, simply a redirecting of energy as men became aware there was no longer a central authority, that every man must shift for himself and that power henceforth would go to him who could grasp it. It was a common experience throughout the western world but where, with most other peoples, the struggle fairly rapidly polarised itself into a two-way tussle between a monarch, who stood for a restoration of central authority, and barons, who had a vested interest in anarchy, in Italy historic accident made the struggle four-cornered. There was a so-called Holy Roman Emperor, who was always a foreigner, who claimed sweeping rights over the land but who, in fact, had only his title with which to back up those claims: there was a pope who was usually Italian, who originally had only spiritual powers but who developed into one of the major despots of the peninsula. And there were the cities, each supposedly owning allegiance to one or other of these two powers but whose total freedom was, in fact, limited only by their immediate neighbours and rivals. In the fourteenth century, this triangular tussle between imperial, papal and civic authorities received another dimension with the emergence of the companies of mercenary soldiers, whose only interest lay in short-term financial gain, but whose internal discipline turned them, in effect, into nomadic republics exerting unpredictable strains on the already creaking social fabric.

Emperor and Pope

When, in AD 330, the Emperor Constantine transferred the administrative capital of the Roman Empire to his new city of Constantinople, he divided the empire in effect, if not in law, and created a vacuum of power in the western half. Gradually the Bishops of Rome – who also boasted the title of Universal Pope – grew in stature to fill that vacuum, inheriting many of the styles and attributes, as well as the titular city, of the Caesars. But while they possessed immense prestige, these early popes had little power and, hard pressed by the successive waves of barbarians, they looked for a champion. Early in the ninth century the reigning pope, Leo III, found that champion in the most powerful barbarian ruler in the west, the Frankish monarch Charlemagne. He was invited to Rome and, in exchange for his protecting sword, Leo crowned him emperor on Christmas Day 800. Technically, it was an entirely illegal act. There could be only one ruler of the Roman Empire and he still ruled in Constantinople, even though he now spoke Greek and his court was termed Byzantine, from the older name of the city. But Charlemagne’s coronation simply recognised reality.

‘The Holy Roman Empire of the German nation’ as the hybrid came to be known, was doubtless a fantasy. ‘Neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire’ is the standard gibe against the ramshackle structure and it is true enough. Nevertheless, for a thousand years most Europeans, and Italians in particular, acted as though there were such a thing, or as though there should be. At a time when the northern nations were grappling with the realities of monarchical rule, those Italians who hungered for a centralised authority put their faith in the fantasy. There was, for them, no break between the modern Germans and the Caesars of the ancient city. Annalists had only one chronological sequence from Augustus down to the most obscure Teutonic princeling who could claim the title. During their visits to Rome, emperor and empress were lodged in chambers called Livia and Augustus. Their processions were still adorned with the wolf, eagle and dragon standards. But even this awesome tradition was raised to greater heights by the Christian infusion which saw the emperor as successor to St Paul, Christ’s Warrior, even as the pope was the successor to St Peter, Christ’s Priest.

So the theory. It found its most able expression in the treatise De monarchia, written in the early fourteenth century by Dante Alighieri. Dante was in exile from his city of Florence and his appeal to the Emperor Henry VII to come into Italy and restore order among the battling cities was as much rooted in self interest as in a genuine, noble desire to see the establishment of a Christian Roman Empire. Henry’s expedition in 1310–13, the last true attempt of a Roman emperor to rule his titular land, was a disastrous failure, the ideal collapsing before the reality of inter-city strife. How far and how swiftly the ideal fell was demonstrated in 1354 when a Germanic king was again summoned to Italy to take the crown and bring peace to a land that seemed intent upon destroying itself. But where Henry VII had come in majesty the progress of his son, Charles IV, ‘was more as a merchant going to mass than an emperor going to his throne’, the Florentine merchant, Villani, observed sardonically. Charles’s journey through Italy was undertaken simply to obtain the crown so that, through it, he could peddle his honours and privileges for solid golden florins. At Rome itself he was allowed to stay only the few hours necessary to receive his consecration, and from there he was hurried out to return north ‘with the crown which he had obtained without a sword-thrust, with a full purse which he had taken empty to Italy, with little glory for manly deeds and with great disgrace for the humiliated majesty of empire’. Thus Villani sadly concluded his account, and his sadness is all the more poignant in that he was a staunch republican and a Guelf, a member of a party traditionally opposed to the emperor. Francesco Petrarch, who had inherited Dante’s splendid, hopeless dream of empire, was considerably more forthright. Addressing Charles rhetorically he asked, ‘If thy father and grandfather were to meet thee in the passes of the Alps, what do you think they would say? Emperor of the Romans but in name, in truth you are nothing but the king of Bohemia.’

Nevertheless, side by side with the Italians’ contempt for the emperor himself, was the unquenchable belief in his office as the source of all legality, the true Lord of Italy. Again posterity, particularly non-Italian posterity, encounters a paradox at the very heart of Italian affairs. Burckhardt could say confidently of the appointments made by this Germanic emperor, ‘The imperial approval or disapproval made no difference, since the people attached little weight to the fact that the despot had bought a piece of parchment somewhere in foreign countries, or from some stranger passing through his territory.’ Burckhardt is, moreover, able to cite a fifteenth-century writer, Francesco Vettori, to support his case: ‘The investiture at the hands of a man who lives in Germany, and has nothing of the Roman emperor about him but the name, cannot turn a scoundrel into the real lord of a city.’ And a modern historian, Ephraim Emerton, emphatically makes the point that, ‘What was called the empire, was really a national kingdom, the kingdom of the Germans, imposing itself on less forceful peoples to the north and south and then decorating itself with the borrowed symbols of a sham imperialism.’

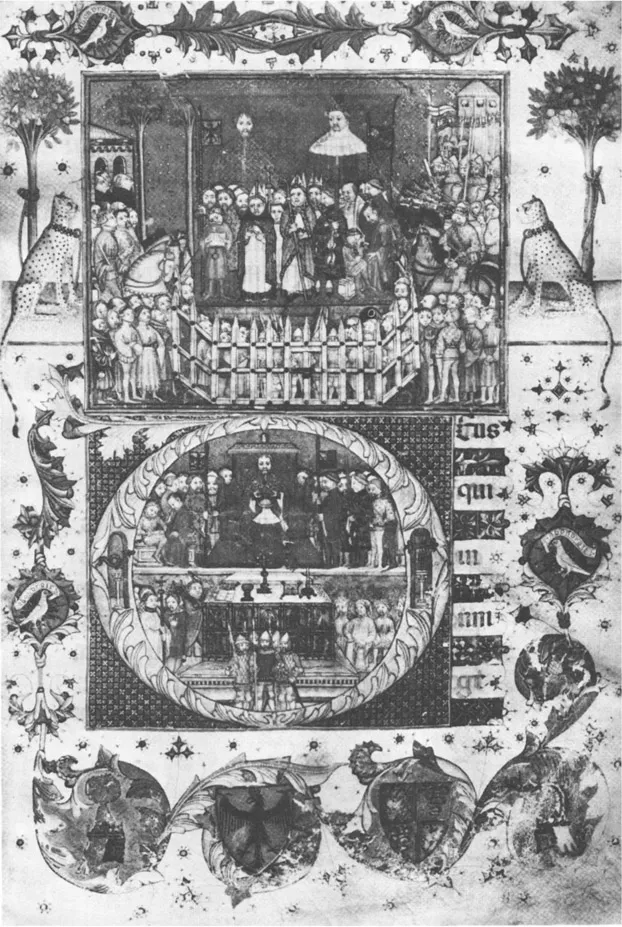

It seems unlikely, to say the least, that Italian merchants would assent – as they did – to the disbursing of several millions of gold florins over the years for the purchase of rights from a Germanic sham. And Francesco Vettori was indulging rather more in propaganda than providing description. He was a Florentine republican and, as such, was seeking to impugn the title-deeds of Florence’s major enemy, Milan, whose principal citizen, Gian Galeazzo Visconti, purchased the title of duke from the Emperor Wenceslas in 1394 - and paid 100,000 florins for it. The sale of that title was one of the weapons used to depose the drunken Wenceslas five years later, the indictment accusing him of corruption because he turned an official into a ruler. Nevertheless, though Wenceslas could be deposed, his Act would not be annulled. That Act had created the first duke in Italy, and over the following two centuries more and more ambitious Italians

The coronation of Gian Galeazzo Visconti by a representative of the Emperor Wenceslas: detail from an illumination by Imbonate

would purchase the glittering titles of duke from the same ‘Germanic sham’ - testimony to the power of an idea over reality.

The theory of the Holy Roman Emperor saw in emperor and pope not the conflicting authorities they became, but a duality appointed by God himself, the one to rule over the souls of all men, the other over their bodies. Rarely was this harmony attained. Ẅith an occasional setback, papal power increased at the expense of its divinely ordained protector until that day in 1300 when Pope Boniface VIII could disclose himself to the pilgrims thronging into Rome, throned and crowned, shouting, ‘Ego, ego sum imperator.’ Boniface could challenge an imperial puppet with safety, but made the mistake of assuming that he could do the same with a real territorial monarch, Philip IV of France. Ostensibly, the cause of their quarrel was the humdrum subject of taxes: in reality it was to decide where power lay. ‘It is necessary for the salvation of all human beings to be subject to the Roman pontiff’ was the burden of Boniface’s most famous Bull, Unam Sanctam. He lost the battle, lost it not metaphorically in a debating chamber but actually, physically. Even those who hated the man – and there were many – professed themselves ashamed and appalled at the treatment meted out to him by a commando of Frenchmen and Italian renegades who, in the little city of Anagni in 1303, seized his sacred person, the ultimate humiliation of the Papacy, as reaction to its ultimate claim to dominance.

Boniface died in Rome. His successor died after a brief reign and Clement V, a Frenchman elected in France in 1303, saw no pressing reason to enter that violent, undisciplined city, nor indeed to enter a land where the person of even the High Priest of Christendom was not safe. Hindsight makes it appear that the so-called ‘Avignonese Papacy’ was a deliberate creation. More likely, it came about simply as a result of human procrastination. That first Avignonese pope, Clement V, made no clearcut declaration of his intention to stay: rather, one can imagine him postponing the unpleasant necessity of returning first day by day, then week by week and finally month by month. It was not until 1336 that the great Palace of the Popes was begun in Avignon by his successor, John XXII, and another sixty years were to pass before it was completed. But whether the ‘Babylonian captivity’ in Avignon, as Petrarch termed it, was deliberate or not, the result was the same. The Papacy became divorced from the land of its origins, but still claimed those revenues and privileges which it had enjoyed as an Italian institution. To enforce those claims, the Avignonese popes sent legates into Italy who could not have been better chosen to enrage Italians. ‘Demoni incarnari’, St Catherine of Siena called them in her vehement Tuscan fashion. ‘Evil pastors and rectors who poison and putrefy this garden.’ Bitter though it was to witness the pope as a French ‘captive’, infinitely more bitter was it for Italians to submit to the demands of foreign legates and watch Italian wealth pass into French hands. One by one the cities broke away from their allegiance, acknowledging still their filial obedience to the Vicar of Christ but rejecting, vigorously, the claims of the papal monarch.

For the Papacy was not simply a spiritual or even an administrative organisation, but a very powerful territorial sovereignty. In addition to the city of Rome itself, the popes ruled, as sovereign, a wide swathe of land that stretched across the entire width of the peninsula, the so-called States of the Church. Supposedly, it had been granted to the popes by Constantine (see Chapter 3) and was an endless source of bitterness and dispute. ‘It is now more than a thousand years since these territories and cities have been given to the priests, and ever since then the most violent wars have been waged on their account and yet the priests do not now possess them in peace, nor ever will be able to possess them. It were in truth better before the eyes of God and the world that these pastors should entirely renounce the temporal dominium … Truly, we cannot serve God and Mammon, cannot stand with one foot in heaven and the other on earth.’ So wrote the chronicler of Piacenza, Giovanni de’ Mussi, in the early fourteenth century. His protest was to be echoed again and again over the centuries, until, in 1870, the Papacy was forcibly deprived of that temporal dominium.

The Papacy returned to Rome in 1377 - but even this return merely precipitated the far worse evil of the Schism, with an Italian pope in Rome and a French pope in Avignon mutually excommunicating each other. The Schism healed, finally, in 1417 when an Italian pope, Martin V, established himself in Rome. But by then the cities of Italy had become accustomed to treating their Holy Father as another temporal rival to be outfought, outwitted or simply cheated like any other.

The Donation of Constantine: mural from the Church of Santi Quattri Coronati, Rome

The cities

By no means all Italians regarded the fall of the Roman Empire, and the consequent ending of central control, as a disaster. Leonardo Bruni, who wrote the first true history of Florence in the 1440s, and his contemporary, the papal secretary, Flavio Biondo, who attempted to make a survey of Italy from AD 412 to 1414, both believed that the demise of the empire allowed the cities to develop their true natures. In his study of the early Italian republics, Daniel Waley calculates that, at the end of the twelfth century, ‘some two or three hundred units existed which deserve to be described as city-states’.11 The story of Italy over the next three centuries is a story of political cannibalism as these city-states absorbed each other, the hundreds becoming scores, then dozens and finally a handful. And an integral part of the story is the transformation of the communes, the ‘free cities’, into states ruled by one man, or controlled by one family, the ‘despotisms’. Republican propagandists distorted history by dramatising that transformation, turning it into a black and white story where an unscrupulous, bloodthirsty ‘tyrant’ imposed his will upon a freedom-loving, but disorganised ‘people’. The reality was seldom as satisfyingly clearcut as that.

The communes, the ‘free cities’, had begun to emerge as identifiable entities from the tenth century onwards. Even contemporaries seemed uncertain as to what they meant by ‘commune’: the word could be verb or noun, sometimes referring to an action being taken ‘in common’, sometimes as a formal community, lending itself to that punning in which Italian writers delighted. Thus a Dominican preacher in Florence informed his congregation that, ‘You should promote the good of the commune because that which is done in commune should be for the common good (pro bono communis).’ Perhaps the best definition of a commune was one made by a Jewish traveller in Italy who noted that in these cities ‘they possess neither king nor prince to govern them, but only judges appointed by themselves’.

It was these ‘judges’ or elected officials of the city who turned the commune into a despotism. Allowing for his emotive use of the word ‘corrupt’ Machiavelli’s theory for this is admirably succinct. ‘Cities that are once corrupt and used to the rule of princes can never again be free. One prince is needed to extinguish another and the city can never know peace, save by the creation of a new lord.’

The evolution of the Milanese ‘despotism’ illustrates this dictum perfectly. In 1262 Pope Urban IV appointed Ottone...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 The geographical expression

- 2 Florence: the search for the past

- 3 The throne of St Peter

- 4 The paradox of Venice

- 5 The warrior princes

- 6 Domestic interior

- 7 The social matrix

- 8 The Renaissance manifest

- 9 The golden age

- Notes and sources

- Appendix I. A note on Italian currencies

- Appendix II. Genealogies

- Appendix III. Popes and Venetian Doges

- Appendix IV. Chronological outline

- Bibliography

- Index