- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides an overview of Tanzania, one of Africa's economically most distressed, socially most innovative, and politically most controversial countries. Focusing on the last three decades, it glimpses into the rich Tanzanian past and reflects influences from the world's major cultures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tanzania by Rodger Yeager in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Origins of Tanzania

Geological changes in eastern Africa during the Miocene epoch, about fifteen million years ago, had the effect of preparing the region for human society. Huge tectonic upheavals raised a forested upland by about 900 meters (3,000 feet) and created the highlands of contemporary Ethiopia, Kenya, and mainland Tanzania. Under the force of this vertical thrust, volcanoes erupted and the earth’s crust cracked and collapsed. Thus was formed the Great Rift Valley, which today extends from north of the Gulf of Aqaba to south of the Zambezi River.

As time passed, the volcanoes became inactive and most were weathered to a fraction of their former size. The floor of the valley sank even lower and many lakes were created, of which only a few remain along the eastern and western branches of the Rift. In Tanzania, these lakes include Natron, Eyasi, and Manyara in the east and Tanganyika, Rukwa, and Malawi to the west and south. Areas lying between the walls of the eastern and western Rift were cast under permanent rain shadows, depriving the tropical forests of essential moisture and providing conditions favorable to the savanna of grass and scattered trees that now predominates in central Tanzania. This savanna country became the scene of a crucial chapter in human evolution.

Precolonial Tanzania

The Birthplace of Humanity

The Miocene was the age of the arboreal apes. These primates were heavily dependent on the trees for their food and shelter. As the forests receded, a small apelike hominoid, Ramapithecus, became adapted to the wooded fringe. Ramapithecus eventually gravitated to the open country and lakes of the Great Rift Valley and there gave rise to still other hominoids including human beings.

The search for our evolutionary progenitors continues near the surviving and extinct lakes of the Rift.1 Tanzania is home to two pioneering discoveries in this quest, made by the remarkable family of prehistorians Louis and Mary Leakey. In 1959 Mary Leakey came upon the broken remains of a humanlike hominid, Zinjanthropus boisei (East African man). The find was made at Olduvai Gorge, the site of a vanished lake on the edge of the Serengeti Plains. A few years later, her son Jonathan discovered Homo habilis (able man) also at Olduvai. Compared with Zinjanthropus, Homo habilis was a highly skilled toolmaker. Both creatures lived at various eastern African locations during the Lower Pleistocene epoch, between three million and one million years ago. Even older protohumans have been found more recently, notably by another Leakey son, Richard, near Lake Turkana in Kenya. Still, Tanzania’s Homo habilis continues to be regarded as the most direct early ancestor of Homo sapiens.

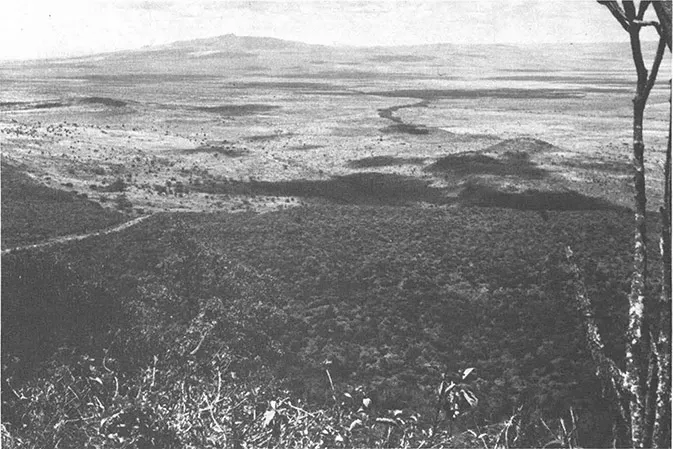

The Great Rift Valley (photo by Rodger Yeager)

Tanzania played host to the first chapter of the human saga. Unfortunately, no lineal connection can yet be made between the ancient hominids of the savanna and the people who later populated eastern Africa and the rest of the world. As far as we now know, the human history of Tanzania began about 10,000 years ago, when Khoisan-speaking hunters and gatherers settled sparsely along the eastern Rift to the south of Olduvai. These forerunners of the modern Hadzapi and Sandawe peoples may have been the first Tanzanians.

The Settling of Mainland Tanzania

From the beginning of the first millennium B.C., the Great Rift Valley served as a highway along which immigrants passed into the northern and western parts of what is now mainland Tanzania. The first new arrivals were a Cushitic-speaking people from southern Ethiopia, who migrated through the eastern Rift until they reached a part of north-central Tanzania that was already occupied by Khoisan hunters and gatherers. As cattle herders, these migrants found an ecological niche in the virgin grasslands of the north and lived interspersed with their neighbors in much the same way that the modern Burungi, Iraqw, and Gorowa Cushitic speakers today share space with the Khoisan Hadzapi and Sandawe.

The first millennium A.D. brought a much larger influx from the west, composed of Bantu-speaking peoples who probably originated in what is now southern Nigeria and Cameroon. These were iron-working cultivators who preferred the wetter areas of western Tanzania and the fertile volcanic mountains of the northeast. The Bantu were thus spared the necessity of competing extensively with the established hunters, gatherers, and pastoralists of the dry savanna.

This balance of people and land use was disturbed between the tenth and eighteenth centuries by a succession of Central Sudanic, Nilotic, and Paranilotic migrations from the north and northwest.2 These grain-producing and herding societies infiltrated the western and northern parts of mainland Tanzania, encroaching upon and in some cases mixing with the Bantu speakers already living there. This same process of migration, conflict, and partial assimilation occurred east of the Rift, until the northeastern highlands were populated by sedentary farming communities bordered by seminomadic groups of pastoralists. Survivors of these early cattle keepers include the Maasai, who also roam over a large area in the northwest. Lowlands adjacent to the Indian Ocean coast were occupied by small societies of Bantu-speaking cultivators.

Because of the constant movement and mixing of peoples between the tenth and nineteenth centuries, it is in most cases not possible to trace the precise cultural origins of Tanzania’s contemporary ethnic groups. One demographic consistency does emerge from the time when the mainland was first settled. The highest human population densities were established in the geographically peripheral coastal areas and interior highlands, with relatively few people inhabiting the semiarid steppe between the eastern and western branches of the Great Rift Valley. This historic settlement pattern bears important implications for social, economic, and political relations in modern Tanzania.

Zanzibar and the Coast

The early societies of the Tanzanian coast faced eastward instead of toward Africa and evolved differently from those of the interior.3 Before 500 A.D., written reference was made to coastal Tanzania in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a Greek trader’s guide. It is fairly certain that yet earlier visits were made by merchants from Egypt, Assyria, Phoenicia, Greece, India, Arabia, Persia, and even China. By the ninth century, Arabs and Shirazi Persians were trading regularly on the coast, eventually establishing a string of settlements on the offshore islands of Pemba, Zanzibar, Mafia, and Kilwa Kisiwani. As these entrepots became more permanent, Arab and Shirazi communities intermingled with Bantu-speaking mainland groups and a new culture—the Swahili—began to emerge.4 By the thirteenth century, the Shirazi-ruled city state of Kilwa Kisiwani controlled the entire eastern African trade in gold, ivory, slaves, and other up-country products. Kilwa’s dominance lasted until the fifteenth century, when the Arab city-states of Zanzibar and Mombasa (in what is now Kenya) gained ascendancy.

Portuguese conquest of the coast delayed the further development of this increasingly Africanized Arab hegemony. The explorer Vasco da Gama first visited eastern Africa in 1498, and by 1506 Portugal had taken control of the city-states and their Indian Ocean trade. Portuguese suzerainty over the Tanzanian coastal area was lengthy but tenuous. By 1729 a group of Omani Arabs had seized power over all settlements north of the Ruvuma River, which later became the boundary separating Tanzania from the Portuguese colony of Mozambique. Omani domination continued into the nineteenth century under the aggressive Busaidi dynasty.

During this time, trade increased with the interior and began with the United States and several European countries. Seeing the potential of this commerce, Sultan Said (1791–1856; reign, 1806–1856) transferred his capital from Oman to Zanzibar in 1840. There he sponsored the development of a slave-dependent plantation economy that quickly made Zanzibar the world’s leading producer of cloves. Said also extended commercial relations with the mainland, emphasizing slave trading for the first time and enlisting the support of several acquisitive and powerful African societies, including the west-central Nyamwezi. By the early 1850s an important trading center had been established at Tabora, in the heart of Nyamwezi country.

Mainland Tanzania experienced its last great migration in the 1840s, when the southern African Ngoni crossed into Rukwa and proceeded to conquer and mix with peoples living in a vast area between the southern coast and Lake Tanganyika. The invasion actually furthered Zanzibar’s commercial involvements on the mainland, once the Ngoni had joined in the slave trade. Far more powerful invaders were required to destroy this blossoming mercantile empire. These were the colonizing Europeans.

The Early Colonial Period

The colonial “scramble” for Africa began in a rather desultory manner throughout the continent, and no less so in Tanzania where Europeans and North Americans pursued limited interests for more than fifty years before the imposition of formal colonial rule. Chief among these early attractions was trade, which focused outside attention on Zanzibar and the commercial network controlled by Sultan Said. On the basis of private initiatives and a treaty concluded with Said in 1833, the United States opened a consulate on Zanzibar in 1837. Britain followed suit in 1841, a move that allowed it freer access to the Tanzanian trade and permitted more effective implementation of the Moresby Treaty of 1822, an Anglo-Zanzibari agreement formalizing Britain’s attempt to end the eastern African slave trade. Zanzibar consented to free-trade treaties with France in 1844 and the Hanseatic German republics in 1859. Western commerce and British political influence continued to expand until administrative colonialism overtook Zanzibar in 1890.

Using Zanzibar as a point of departure, European explorers and missionaries penetrated the mainland during the middle and late nineteenth century. Although sometimes inadvertently, secular and proselytizing explorers helped define future colonial boundaries. They also paved the way for Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries. Even though their achievements in religious conversion were modest, the missionaries made two important contributions to the massive socioeconomic and political changes that were about to occur. First, beginning with David Livingstone, some of these clerics supplemented their spiritual messages with practical instruction in the mechanical and agricultural arts. Missionaries also identified a potential lingua franca in the coastal Kiswahili language, itself a mixture of Bantu, Arabic, and other tongues. They transliterated Kiswahili from Arabic script into the Roman alphabet, providing a useful tool for future colonial administration and economic exploitation.

German East Africa

By the early 1880s, a newly unified Germany was searching for economic lebensraum and a political place in the sun vis-à-vis other European powers. These needs persuaded Chancellor Otto von Bismarck to support the entrepreneurial activities of one Karl Peters and his Society for German Colonization. Peters traveled to the area of mainland Tanzania in 1884 and signed a series of agreements with local rulers that ceded administrative and commercial “protection” to the society. In 1885 the society was granted a German government charter to administer on the mainland a largely undefined territory, which it transferred to a new organization formed by Peters, the German East Africa Company.

This display of German ambition gave pause to the British and even more so to the current sultan, Barghash (1833–1888; reign, 1870–1888), who correctly interpreted it as a direct threat to Zanzibar’s mainland trading empire. In an act typical of the times, German and British officials met without consulting the sultan and agreed to the formation of a German protectorate north of the Ruvuma River and south of what is now the international boundary between Kenya and Tanzania. An Anglo-German accord of 1886 permitted the sultan to retain control over Zanzibar, Pemba, Mafia, and Lamu islands, in addition to a coastal strip extending 6 kilometers (3.5 miles) inland. In 1888 the Germans forced the sultan to grant a fifty-year lease on the coastal strip and thereby gained full economic and political jurisdiction over the mainland.

After five years of merciless economic exploitation, political oppression, and local tax revolts in the coastal towns, the German East Africa Company found itself near insolvency and under increasing attack in the German Reichstag. In 1891 the Berlin government reluctantly assumed direct responsibility for German East Africa, following an 1890 Anglo-German agreement that fixed the colony’s western boundaries, instituted a British protectorate over Zanzibar, and gave Germany permanent ownership of the coastal strip. The Reich’s eagle finally flew over all of mainland Tanzania, as well as an area that Germany was to lose to Belgium after World War I and that eventually became the independent states of Rwanda and Burundi.

At first organized as a military dictatorship, the German colonial regime quickly established a reputation for political ruthlessness and modernizing achievement.5 As they sought to formalize their rule, European commanders found that many of Tanzania’s African societies were not hierarchically structured and possessed few governmental institutions that could be used for colonial purposes. For the sake of administrative efficiency and to compensate for a lack of German personnel, a governing system was created placing Swahili and Arab agents, the maakida, in charge of local headmen, termed majumbe. In places where powerful African chiefs were discovered, these too were incorporated into the administration under the supervision of maakida.

From the point of initial contact, African resistance was mounted against the Germans and against this system of alien rule that put Europeans, Arabs, and coastal Africans into locally unfamiliar positions of almost unlimited power. At a time when German military expeditions were still trying to pacify the interior, the Hehe people of present-day Iringa Region were also expanding by conquest. An armed conflict ensued between the Hehe and the Germans, lasting from 1891 until the Hehe were finally defeated in 1898. Yet other rebellions were mounted against the expanding colonial government and the interests it was intended to serve.

The initial economic policy emphasis was on European plantation agriculture, although African cash cropping was also permitted in areas where Europeans had not settled. The first farms were near the coast and in the fertile and comparatively temperate northeastern highlands, between the Usambara Mountains and Mount Kilimanjaro. There coffee, cotton, sisal, and rubber became the favored crops. Effective commercialization of these enterprises and a further expansion of European farming required efficient transportation facilities and readily available land and labor. The colonial government approached the transportation problem by developing a northern road network. A railroad was likewise completed in 1911 from the port of Tanga to Moshi, a garrison town at the base of Kilimanjaro. Another railroad was constructed to link western Tanzania with the newly constructed administrative capital and port at Dar es Salaam. By 1914 this line reached Kigoma, on Lake Tanganyika, opening a vast territory to possible European settlement.

As the colony was made more accessible, the rate of German immigration increased. To provide for this growth, large tracts of arable land were confiscated—or, as the British later put it more delicately, “alienated”—from African cultivators and pastoralists. With the assistance of the maakida, labor was recruited by impressment and through the less direct but no less effective means of the hut tax. Africans could work off the tax or pay it by earning the necessary money. Land confiscation and this form of indentured servitude led to considerable unrest and contributed to German East Africa’s most serious ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Origins of Tanzania

- 2 The Ecology of Change

- 3 Toward Socialism and Democracy?

- 4 Toward Socialism and Equality?

- 5 Toward International Leadership and Autonomy?

- 6 The Tanzanian Experiment After Three Decades

- Notes

- Suggested Readings

- Acronyms

- Index