eBook - ePub

Plants And Harappan Subsistence

An Example Of Stability And Change From Rojdi

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book aims to interpret the archeobotanical remains at the site of Rojdi, in northwest India, with reference to diet and environment and within a socio-economic framework. It discusses artifactual material which associates it with the 'Harappan Cultural Tradition'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Plants And Harappan Subsistence by Steven A. Weber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The principal aim of this research project was to interpret the archeobotanical remains at the site of Rojdi, in northwest India, with reference to diet and environment and within a socio-economic framework. By regarding human-plant interactions as essentially responses to both social and natural opportunities and constraints, we can approach a number of specific issues concerning Rojdi, the wider region of Gujarat, and ultimately the Indus Civilization as a whole.

Paleoethnobotanical research in South Asian archeological sites has hi general been limited to noting the presence of archeobotanical remains at particular time periods. As a consequence, little is known about how the distribution of plant remains changes through time at a particular site, or through the phases of evolution of Harappan culture as a whole (Vishnu-Mittre and Savithri 1982). No more than 80 sites in all of South Asia dating to earlier than 1000 B.C. have yielded plant remains of some form. Few of these sites contained more than a single taxon or represented more than an accidental find. Although the limited data base has hampered our ability to infer the occurrence and change of plant-use patterns, it has by no means impeded the construction of theories or models which attempt to explain Harappan subsistence. It is important to assess the status of our knowledge periodically, and examine critically the theories that have been developed which use this information. The most useful way in which to do this is to collect new data, most importantly data which includes differing portions of plant material at various levels of occupation within South Asian sites.

The collection of this data must commence at the level of the single site. A single site is an easily defined unit of analysis that is free of the ambiguities that presently plague our definitions of the Harappan Civilization and its various subregions. The single site that is the focus of this book is that of Rojdi, which, while being located in a peripheral region of the Harappan Civilization, namely Gujarat, has artifactual material which associates it with the 'Harappan Cultural Tradition'. Since it was occupied from the middle of the third millennium B.C. to the beginning of the second millennium B.C., which coincides with a critical period of transition from the Mature Harappan Phase to the Late Harappan Phase, an in-depth analysis of the Rojdi subsistence system should add to our knowledge not only of this site, but also of this region of Gujarat, and perhaps of the Harappan Tradition in general.

A paleoethnobotanical research project at Rojdi was therefore developed, with its primary purposes to document the inhabitants' use of cultivated and wild plants to examine variability and change in that use, to provide information on the habitat, and to attempt to identify and differentiate all human-induced and naturally induced changes occurring in the local environment during all phases of occupation, A secondary purpose was to examine the wider significance of the Rojdi data by comparing the Rojdi archeobotanical record with material collected from other sites, and to attempt to account for the variability in the temporal and spatial distribution of plant remains. Apparent variability in archeobotanical distributions from South Asian sites has already been used in theories dealing with plant origins and movements (e.g., Harlan 1976, Hutchinson 1976, Costantini 1979a), related population and settlement dynamics (e.g., Possehl 1986,Jarrige 1985), the evolution of region-wide subsistence systems (e.g., Allchin 1977, Possehl 1979:539, Ratnagar 1986), influence from areas outside South Asia (e.g., Sarma 1972, Possehl 1986), and differing plantuse strategies among local populations (e.g., Weber 1988, 1989a). However, biases in the sampling and/or methods of analysis have not always been recognized. Critical examination of this data, along with the use of data from Rojdi, should lead to a better understanding of the human-plant interrelationship during Harappan times.

A further, subsidiary aim of this work is to develop new explanations for plant occurrences and their evolution in South Asian prehistory. These new explanatory models must be tested by future work.

The following chapters include attempts to address certain issues and answer some fundamental questions about subsistence and plant use at Rojdi and beyond. These include:

1. Description and Interpretation of the Rojdi Archeobotanical Record

What plant taxa can be identified from the occupational (i.e., archeological) deposits of Rojdi, and what were their possible uses? What does their presence suggest about the condition of the local habitat and the types of environmental constraint imposed on the inhabitants? What does the proportional representation of each taxon suggest regarding the settlement, its subsistence strategy, farming practices, cropping seasons, water management system, and human involvement itself? How do plant identifications compare to those from other sites of comparable age, and how well do they fit into existing theories about Harappan subsistence systems?

2. Description and Interpretation of Change in the Rojdi Archeobotanical Record over Time

What changes in the Rojdi plant record can be identified during the phases of occupation of the site? What are the range of possible causes for changes occurring during the Rojdi occupation? Are dietary shifts or human-induced environmental changes indicated? Are the types of change seen at Rojdi identifiable in other sites around the beginning of the second millennium?

3. Description and Interpretation of the Wider Significance of the Archeobotanical Material Recovered at Rojdi

Was Rojdi part of a regional subsistence system and does it reflect a pattern of plant use typical for Harappans or Sorath Harappans? What, if any, common elements are evident in Sorath Harappan diet regarding the interrelationships between plants and animals, between wild plants and cultivated ones, and between indigenous and non-indigenous species? What are the implications regarding interaction with other regions and peoples, and what is the significance and impact of both indigenous and non-indigenous cultigens on Rojdi and on the Harappan Civilization as a whole? What are the possible origins of the non-indigenous species and by what routes could they have entered South Asia and Rojdi?

Chapter 2

Archeological Perspectives on the Region

In order to adequately understand the site of Rojdi and its temporal framework, a brief discussion of the prehistory and protohistory of South Asia is in order. This will not only give a cultural, historical perspective to the research but will enable one to understand the significance of the questions being asked. Therefore, this chapter will present the prehistoric context in which Rojdi was inhabited, how Rojdi fits into existing schemes and theories of South Asian prehistory, where the inhabitants of Rojdi may have come from and what might have happened to them after the site was abandoned, what other groups of people may have been interacting with Rojdi, and which populations or sites are best suited for comparisons with Rojdi. To accomplish this task three subsections will follow: a discussion of the current theoretical status of South Asian archeological and the ways in which the prehistory of this region is best viewed, a brief summary of the Harappan Civilization, and an outline of the archeology of Gujarat.

Status of South Asian Prehistory

Research into prehistoric and protohistoric South Asia has advanced from early concerns with the regional and sequential relationships of lithic assemblages and ceramics, and the projection of artifact typologies and technology through time, to a more interdisciplinary approach oriented toward the reconstruction of past ways of life that operates with a more sophisticated and integrated concept of culture (e.g., Sankalia 1974, Allchin and Ailchin 1982, Possehl 1982, Jacobson 1986). Many important archeological discoveries in the last 20 years have expanded our basic knowledge regarding South Asian prehistory (Shaffer 1981, 1988:5). This is especially true in the area of the Harappan Civilization, where such work as Mughal's explorations in the Cholistan Desert have changed our understanding of Harappan settlement patterns (Mughal 1970, 1972, 1975, 1980, 1982, 1988). The interpretation of South Asian prehistory has been subject to much controversy, resulting from the limited number of excavated sites, the observed diversity in this limited database, and the desire of many scholars to explain this diversity in terms of similarities to and differences from other regions of the world. Further, the frequent tendency to view the prehistory of South Asia as a single sequence of events, with each stage of development leading neatly into the next, has also caused problems, since different regions developed at different rates and at different times, each interacting with, or being influenced by, other areas (Possehl 1976, 1980).

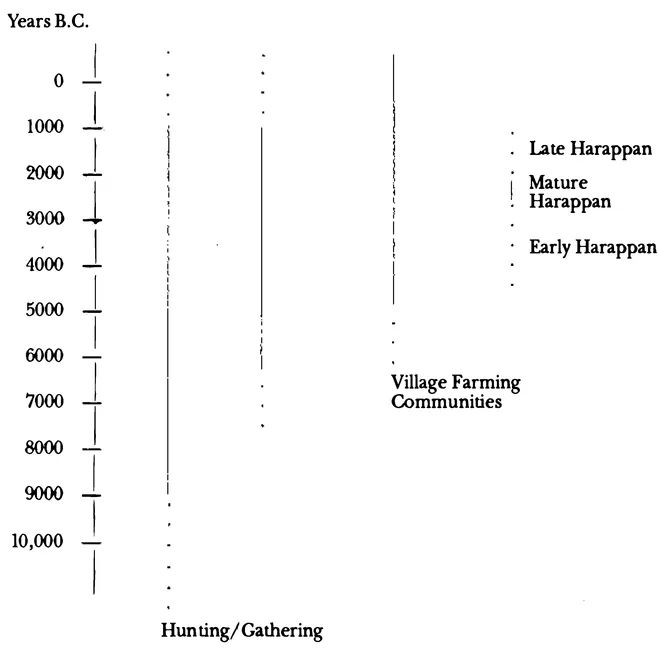

Figure 2.1. South Asian chronology. Adapted from: Possehl et al. (1985).

Simultaneous developmental and stylistic differences among sites, incorporating Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Harappan cultures, make up a pattern that is basic to South Asian prehistory (figure 2.1). Archeological reconstruction implies the existence of similar but distinct groups of people in a common region, possibly interacting, yet maintaining different forms of economic adaptation (i.e., farmers, hunter-gatherers, and pastoralists as well as groups using a combination of economic strategies) (Fox 1969, Agrawal 1982, Shaffer 1986, Possehl and Rissman in press). This occurrence of archeological sites with different forms of adaptation within a common region is often described as a 'cultural mosaic' (Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1987:14, Possehl and Rissman in press: 45).

The present trend in South Asian archeology is to move away from unitary, linear models of evolution, and toward viewing subregions of Harappan Civilization in a manner which allows the researcher to explain the cultural diversity expressed in the artifactual record. Since most of the archeological work in the northern portion of South Asia has focused on the Harappans or Indus Civilization, and since Rojdi was occupied during the time of the Harappans and within the regional sphere of what is considered the Harappan Cultural Tradition, it seems appropriate that any efforts to put Rojdi in some form of cultural and temporal framework should begin with a discussion of the Harappans.

Harappan Civilization

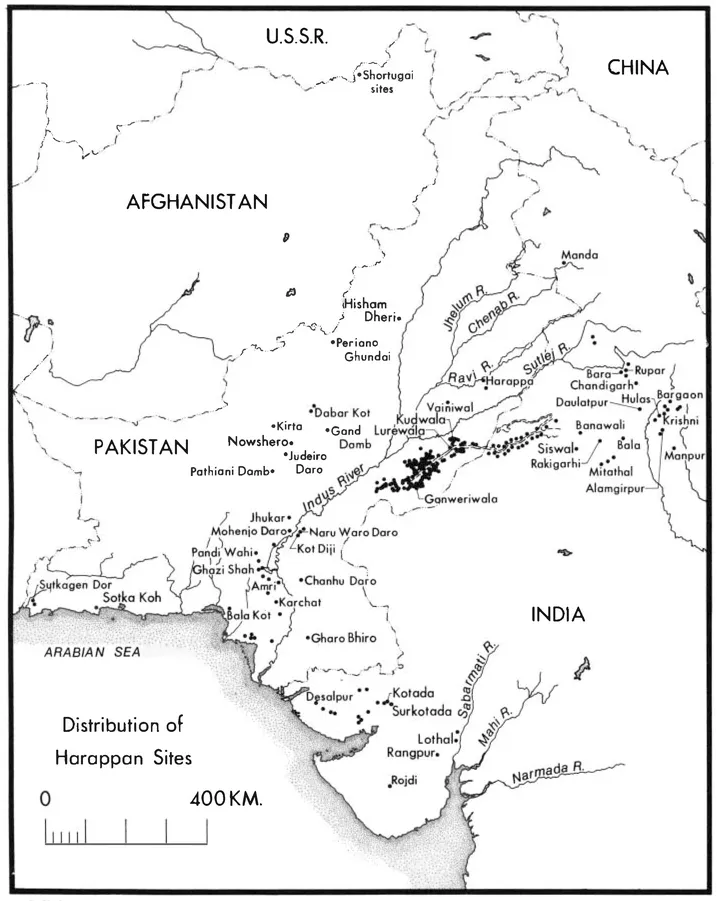

While most of what is known about the Harappan Civilization is based on the excavations of a few large cities like Harappa and Mohenjodaro, the Harappan Cultural Tradition covered an area of around 300,000 sq mi (480,000 sq km) and includes hundreds, if not thousands of sites (figure 2.2). Sites with Harappan-like artifacts can be found dispersed through a geographical area which is larger than that of contemporaneous civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia.

From the earliest village communities of the seventh millennium B.C., like Mehrgarh, archeologists have observed around 4000 years of cultural development in northwestern South Asia, culminating, in the Mature Urban Phase of the Harappan Civilization (Posselh and Rissman, in press: 55). Their diversity notwithstanding, sites of the Harappan Civilization are best understood in terms of a single temporal framework. Therefore, a three phase approach using the terms Early Harappan, Mature Harappan and Late Harappan will be used here (see Mughal 1970).

The early Harappan Phase begins with initial development of food production in the Greater Indus Valley and continues to the beginning of the Mature Phase around 2500 B.C. Presently, the data suggests that the fusion of a number of different cultural groups occurring during the Early Phase, including the inhabitants of Bagor, Hakra, and Kot Diji, is the basis of what has become known as the Harappan Tradition (Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1987: 12). While the Early Phase spanned some 4000 years, it is in the final 150 years of this phase that we observe a more rapid change which ushers in the Indus urbanization (Possehl and Rissman in press: 55). During this time a number of features or traits are evident that imply a development toward more sophisticated town life. These features, including enclosing walls or fortifications, intensive agriculture, community

Figure 2.2. Map of Harappan sites. Source: Possehl and Raval (1989: 4).

planning, standardized brick sizes, metallurgy, increased settlement size, some styles of pottery and beads, and even some indications of longdistance trade and the beginnings of a script, had roots in the antecedent cultures scattered across almost as vast a region as that covered by the Harappan Tradition itself (Jacobson 1979:486).

While one or more of these traits occur in most early settlements, precisely how these regional traditions coalesced into a more culturally uniform civilization which includes cities, standardized town planning, seals, a uniform standard of weights and measures, and a form of writing remains unknown. However, a number of conditions have been suggested which may have influenced this process. Shaffer and Lichtenstein (1987:12) have identified four causal conditions: (1) changes in socioeconomic organization which may have allowed for the expansion of crafts and trading activities; (2) a need to consolidate access to important geographical regions in a manner which would minimize conflict between competing social units; (3) increasing interaction through competition for resources in the region, arising out of more stressful conditions; and (4) a history of socioeconomic interaction resulting from exploitation of a common region and facilitated by membership in a common cultural tradition. Other factors may have included a need for an organised response to flood disasters, which may have helped produce the types of administrative mechanism that survive as regularities in the archeological record (Gupta 1978; Jacobson 1979:486-487), or the impact or stimulus of long-range trade and commerce (Lal 1979:95).

While the conditions that led to the development of an urban civilization in the Indus Valley are subject to debate, the rapidity and the extent of the development is clear. It is referred to as the Mature Harappan Period beginning at about 2500 B.C. and lasting until about 2000 B.C. In the Indus Valley, the core area of the civilization, this period is characterized by the full-blown development of urban centers such as Mohenjodaro and Harappa. A distinctive constellation of artifactual and architectural styles are found at site after site throughout this phase. While these distinctive styles are different from those which immediately preceded and followed the Mature Harappan Phase, they largely represent the culmination of a long process leading steadily toward the urbanization of the Indus Valley.

While some crafted items that were present in Early Harappan sites increase in frequency, for example copper implements and stamp seals, other products like specific types of black-painted red pottery and etched carnelian beads appear for the first time. At the same time as this increase in industrial production, there appears a significant growth in the size of some settlements, with the occurrence of twin mound patterns in many of the larger ones (e.g., Mohenjodaro, Harappa, and Kalibangan). Also found are examples of public architecture such as plazas, platforms, streets, multiroom non-habitation structures, and hydraulic features such as drains, wells, and tanks. The artifacts from Harappan sites suggest a high level of technological sophistication implying a certain amount of craft specialization. The food economy seems to be based on domesticated plants and animals, including wheat, barley, millets, sheep, cattle, goats, and water buffalo.

The Mature Phase is a period of expansion in which settlements with Harappan-like artifacts begin to appear in new regions, such as Kashmir, Gujarat, North Afghanistan, and the Makran Coast The distribution of artifacts made from materials that were not available in the locality of these sites (e.g., shells, stones, metals, and intrusive ceramics), as well as the occurrence of a common script, implies the existence of a trading system, and hence communication and interaction across space (Shaffer 1984:8). In sum, the essence of the Mature Harappan Tradition is contained in its script, the homogeneity of its material culture, and a certain degree of historical and cultural continuity.

The social and political systems underpinning the Mature Phase are still not adequately understood. The cultural complexity and homogeneity occurring within the Harappan Tradition does not fit existing models of ranked or stratified society. The lack of identifiable palaces, temples, or exceptionally wealthy burials suggests that the Harappans did not develop a highly structured or centralized political economic organization based on hereditary elites (Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1987:13). In fact, the archeological evidence indicates an absence of restriction upon access to resources, and possibly the existence of non-material expression of status.

Although the Harappans are the best studied and most written about people in South Asia, they were not the only cultural group in the region during the Mature Phase. The wide range of artifactual and stylistic variation within the region influenced by the Harappan Cultural Tradition implies the existence of similar but distinct cultural groups, who were simultaneously competing for resources and maintaining interaction networks (Shaffer 1984, Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1987). As might be expected, the Harappan border regions show an increase in local, supposedly indigenous traits, and a decrease in Harappan styles. A heightened degree of regional expression of Harappan traits and a decline in urban life mark the end of the Mature Harappan Phase. The abandonment of Mohenjodaro, Harappa, Kot Diji, Balakot, Allahdino, Kalibangan, Ropar, Surkotada, and Desalpur was part of this process, although Harappan culture did not cease with th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Archeological Perspectives on the Region

- Chapter 3. Paleoethnobotanical Analysis

- Chapter 4. Status of Paleoethnobotany in South Asia

- Chapter 5. The Site of Rojdi

- Chapter 6. Methods

- Chapter 7. Description and Implications of the Rojdi Plant Material

- Chapter 8. Paleoethnobotanical Reconstruction at Rojdi

- Chapter 9. The Rojdi Plant-use/Subsistence Model

- Chapter 10. Wider Significance of the Rojdi Plant Remains

- Chapter 11. Conclusion

- Bibliography